‘It’s getting harder and harder to hide’ How children living under Russian occupation have secretly continued attending Ukrainian schools

Мы рассказываем честно не только про войну. Скачайте приложение.

The Ukrainian territories currently occupied by Russia had about 900 schools before the full-scale invasion. Many of them are now closed, while the ones still operating openly are using textbooks issued by the Russian Education Ministry. At some of these schools, however, students have continued studying Ukrainian curriculum through online classes. Attending these schools is dangerous, of course, and families take careful measures to avoid detection, such as hiding children’s assignments on USB drives and even moving from cities to small towns, where Russian troops are less likely to come knocking. The independent outlet iStories recently spoke to the principal of a school from Nova Kakhovka in the Kherson region and a teacher from an agricultural school in Melitopol about the challenges and rewards of running Ukrainian schools in occupied territories. Meduza shares an English-language adaptation of their report.

‘I had to become their psychologist’

Anna Bout used to teach biology, German, and civic education classes at a Melitopol lyceum. On the morning of February 24, 2022, her neighbor told her that Russia was bombing the Melitopol Air Base, but she thought he was just drunk. Then, when she arrived at her classroom, she heard “a commotion” coming from the school’s dormitory.

“Everyone was standing with their bags and shouting, ‘War!’ I turned on the TV and saw that everything in Ukraine was burning, there were bombs dropping all over the country, and the newscasters were talking about a full-scale war,” she told iStories. The school’s principal moved classes online so that students and teachers wouldn’t have to walk to the school building. Two days later, the Russian army occupied Melitopol.

On February 28, Anna and her colleagues, her students, and other Melitopol residents began holding street protests every day. When Russian troops started abducting activists and mass protests became unfeasible, Anna began putting up Ukrainian flag posters all over the city. She also did her best to keep supporting her students:

I had to become not their teacher but their psychologist. I would meet with my students and their parents at my home or at the lake near the school. I told them that everything was going to be okay and that they just needed to hang in there. For the students who managed to leave, we stayed in touch by phone. I encouraged them to lie low and take care of themselves.

Anna and her daughter made no secret of their pro-Ukrainian views, continuing to protest and writing about the reality of the occupation on social media. Before long, they started receiving threats, even from their acquaintances; one person wrote, “Burn in hell, Ukrainian scum.” Meanwhile, the occupation authorities had begun murdering and imprisoning pro-Ukrainian activists. In April 2022, fearing they would be targeted as well, Anna and her daughter left Melitopol.

‘There’s no way out’

Iryna, the head of a lyceum in Nova Kakhovka, stayed in the occupied town until August 2022. On the day the full-scale war began, she was at the hospital near Kyiv when she got a call from the school’s assistant principal. She told Iryna that there had been explosions in the town and that parents had shown up to school along with their kids. Iryna told her to let everybody in; the school had a large basement that could serve as a bomb shelter.

The following day, school was called off, but students, parents, and teachers continued to use the basement as a bomb shelter. Iryna decided she would return to Nova Kakhovka. “I had to be strong,” she recounts. “My assistant principal was panicking, and parents were calling me; I had to tell them in a cheerful voice that everything was going to be okay.”

By then, the Kherson region had come under occupation; Iryna wasn’t able to reach Nova Kakhovka until March 14. From that point on, she went to school every day with the teachers, who continued to hold lessons online.

In April, Vladimir Leontyev, the town’s Moscow-installed mayor, called a meeting with the directors of Nova Kakhovka’s schools. He promised to raise their salaries, saying that children’s education was more important than any conflict, but he said they should start holding class in Russian and use Moscow’s textbooks.

Iryna immediately decided she wouldn’t comply. Then, in July, when she was at the school preparing for the new academic year, a group of men from the occupation administration showed up with automatic rifles.

“One of them was [Vyacheslav] Reznikov, the former principal of [another school], whom the occupiers had appointed the head of the local education department. Along with him were the Gauleiter’s so-called press secretary, Zoryana Us, and three soldiers with machine guns — pathetic little guys who were smaller than their weapons,” she says.

Zoryana and Vyacheslav sat down, and the gunmen stood behind me. Reznikov started to say, “Don’t refuse, Iryna Petrovna. You’ve done such a great job — you’re ahead of the curve. Our forces have nearly taken Mykolaiv and Odesa; there’s no way out. We need to establish an education system. Other principals will follow your example.” He gave me two weeks to think about it. But I had no intention of even thinking about it. I wanted nothing to do with Russia — I believed in victory and was ready to defend my school to the end.

On August 18, the occupation police took Iryna captive, locking her in a passport office with other prisoners, including another school principal and employees of the town’s legitimate government. The women were given very little food and water, and they had to use an empty mayonnaise jar as a toilet.

Every day during her imprisonment, Iryna was brought in for “chats” with an agent from the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) with the callsign Umar; she never learned his real name.

Meduza has condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine from the very start, and we are committed to reporting objectively on a war we firmly oppose. Join Meduza in its mission to challenge the Kremlin’s censorship with the truth. Donate today.

“He asked me if I’d considered switching our school to the Russian education system. He threatened me, saying I could face 15 years in prison for promoting Ukrainian education in Russia. He accused me of tipping off the Ukrainian military about Russian troops’ positions. [My captors] didn’t touch me, but they tortured the other women with electric shocks, and they told me I would be next,” Iryna says.

On August 23, the fifth day of Iryna’s imprisonment, Umar ordered her to gather the school’s TVs, tablets, and laptops so that her replacement could open the school. After she complied, the occupation authorities finally released her, and she left for Kyiv.

“After all that, I started to see a therapist and a psychiatrist, because there are some things I can only tell a stranger, someone who will bury them inside themselves. I thought that the pain would fade with time, but it hasn’t,” she says.

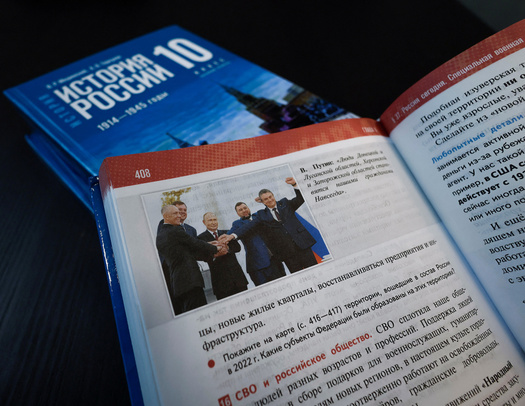

‘Children don’t understand this is propaganda’

On August 26, Iryna’s first day in Kyiv, she let herself cry for the first time since the start of the full-scale war; that evening, she put tea bags on her eyes to relieve the swelling. The next morning, she got to work putting her school back together.

After determining which of her teachers wanted to come back to work, she found new teachers to replace those who left. Then she contacted her students’ parents to inform them that school would continue. “I couldn’t betray my school. I realized that if I could survived life in occupation and captivity, I could do anything,” she says.

By September 1, 2022, a total of 647 students had enrolled in the school. Most of them were either living abroad or under occupation. Before the full-scale invasion, the school had had 637 students.

The families who remained under occupation had to find ways to avoid persecution by Russian security forces while their children attended school in Ukrainian. Many moved from the city to small villages, where there were fewer soldiers and people’s homes weren’t being searched.

The school where Anna worked also continued to operate online, with many of the students logging in from occupied territory. Their old school building, like Iryna’s, was being used by the occupation authorities to teach Russian curriculum; Russian soldiers burned the school’s Ukrainian books and flags in the courtyard outside.

Anna doesn’t know the details of the classes run by the occupation authorities, but her acquaintances who still live in the city have told her it’s “hard to call it education.” For example, her former colleague who used to only teach physical education now teaches four different subjects in Russian, including geography and economics.

Anna’s acquaintances also say that Melitopol is now covered in signs reading “Russia is our homeland” and “Melitopol is Russia” as well as St. George ribbons. “There are thousands of people in Melitopol who are horrified by all of this propaganda. But the scariest part is that we adults — or at least some of us — understand that this is propaganda. But children don’t understand, and there’s nobody to explain it to them,” she says.

One friend who still lives in the city told Anna that she’s seen teenagers there wearing baseball caps and T-shirts with the Russian coat of arms. “But this doesn’t scare me,” Anna says. “It’s not their fault that their parents didn’t evacuate them. I love children and young people very much. We’ll return and all of this stuff will be taken down. Because me and the other teachers are going to do everything we can to ensure they fall back in love with Ukraine.”

Attending Russian schools is now mandatory for children in Melitopol. As a result, Anna says, most of the former teachers she knows have left the field; according to them, “education” in the city has turned into propaganda, and they weren’t willing to make children do activities like coloring Russian flags. Anna’s even heard about cases of soldiers with weapons showing up at families’ homes and ordering them to send their children to Russian schools.

But despite all of the risks, there are still parents in Melitopol who send their children to online Ukrainian schools. Because they have to go to Russian school during the day, they usually attend their Ukrainian classes in the evenings. To protect against raids from Russian troops, many parents take their children to separate apartments for their classes.

“It takes great courage to continue studying at a Ukrainian school while living under occupation,” Anna says.

People are reporting each other to the authorities left and right in Melitopol. A neighbor could come by your apartment and hear you speaking Ukrainian at any moment. It’s getting harder and harder to hide. They tap people’s phones, and there’s a constant risk of them stopping parents on the street and checking what’s on their phones. Families hide class materials in flash drives in secluded corners of their homes.

Over time, according to Anna, the number of students showing up to the online classes has gradually declined. “We’ve had to stop offering entire grade levels,” she says. “By the end of the 2023–2024 school year, there were almost no students left.” This year, Anna’s school didn’t have enough students to continue operating.

‘They give back what the war has taken away’

Unlike Melitopol, Nova Kakhovka has practically no working schools; the occupation authorities have done little in the way of establishing an education system there. “In 2023, the only school that opened in Nova Kakhovka was School No. 10, but it was online,” Iryna says. “Some parents were given groceries and 2,000 rubles ($22) in exchange for enrolling their children there. But nobody’s tracking whether they go to school or not.”

Here, as in Melitopol, parents have to take pains to hide the fact that their kids are studying in Ukrainian schools online. Despite this, Iryna’s school had 568 students enrolled last year. Two of the five students who graduated with honors spent the entire year studying under occupation. They were able to travel to Ukrainian-controlled territory to personally receive their diplomas and medals from Iryna, and they subsequently enrolled in Ukrainian universities.

Even since the liberation of Kherson in November 2022, Iryna says, Nova Kakhovka has been under constant shellfire; often, there’s no Internet or electricity. “Our teachers hold classes for the students there whenever they happen to have Internet access,” she explains.

The teachers try not to discuss the war in class, but they do remind children to take safety measures. For example, they ask them not to climb trees on occupied territory to try to get an Internet connection to send in their homework — something students have done in the past. “If a student doesn’t pass a test, that’s not a threat to their life. We don’t want to put pressure on the kids and their parents,” Iryna says.

I constantly pop in to online classes just to see the children and tell them to take care of themselves. Children need extra support right now, including the ones who are under occupation, the ones who are under fire in territory controlled by Ukraine, and the ones who are abroad, far from their homes.

The students are so eager to attend their classes — they want to spend as much time as possible with their classmates, even if it’s just through a screen. Their homeroom teachers regularly schedule downtime for the students to just talk to each other, throw parties, and generally give them back what the war has taken away: laughter and joy.

Iryna’s school has had 685 students enroll for the 2024–2025 academic year — more than they had before the start of the full-scale war. Many of them are living under occupation.

Anna now works as a translator and coordinator at Melitopol Professional College, which is holding classes online. Like the rest of the faculty, she lives in Zaporizhzhia. She’s also resumed her volunteer work weaving camouflage nets for the Ukrainian military, which she had to stop doing while living under Russian occupation. In May 2022, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky presented her with the National Legend of Ukraine award for her charity work and protests in Melitopol.

Both Anna and Iryna have former students serving in the Ukrainian military, including some who are currently in Russian captivity.

Story by Katya Alexander for iStories. Abridged translation by Sam Breazeale.