‘Our guys’ In Russia’s Buryatia, high military death rates make the war impossible to ignore. A new report reveals how it’s become normalized.

Мы рассказываем честно не только про войну. Скачайте приложение.

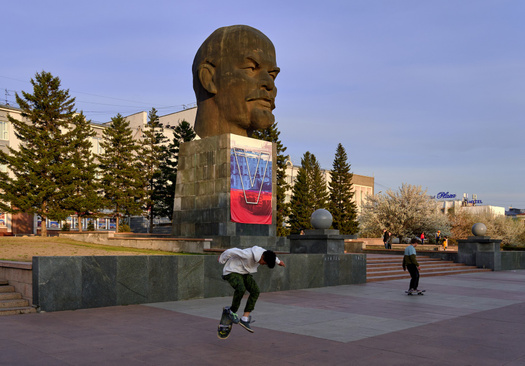

In the fall of 2023, researchers from the Public Sociology Lab (PS Lab) visited three of Russia’s regions — the Sverdlovsk region, Krasnodar Krai, and Buryatia — to study residents’ views on the full-scale war in Ukraine. During their trip, the sociologists managed to conduct 75 in-depth interviews and compile three detailed ethnographic diaries (each with about 110,000 words). Below, Meduza shares an English-language summary of the team’s report from their work in Buryatia, which has paid a higher price for Russia’s war against Ukraine than nearly any other Russian region.

The Republic of Buryatia in Russia’s Far East is one of the regions that has suffered most from the country’s full-scale war against Ukraine. In March 2022, Buryatia accounted for 3.5 percent of Russia’s losses, despite making up just 0.3 percent of the country’s population. During the mobilization that began in September 2022, residents of Buryatia were called up 2.5–3 times more frequently and were killed on the battlefield an average of seven times more frequently than residents of other regions.

Buryatia’s population is relatively small and characterized by strong community ties, which played a significant role in many residents’ decisions about whether to emigrate during Russia’s mobilization campaign. According to local activists, the tight-knit nature of Buryatian society also makes it riskier for individuals to take part in protests, as the consequences can affect not just participants themselves but also their family members and friends.

PS Lab’s researcher spent a little over a month in Buryatia. She split her time between the regional capital of Ulan-Ude, where about half of the region’s residents live, and the village of Udurg, which has a population of less than 10,000.

Buryatia, the war, and decolonial discourse

The largest ethnic groups in Buryatia are the indigenous Buryat people, who make up about 31 percent of the republic’s population, and Russians, who account for about 59 percent of the population.

Even before February 2022, the deployment of Buryat troops in Ukraine was a widely discussed topic in both Russian and foreign media. A major theme of this discourse was the idea that Moscow was demonstrating its colonial nature by treating members of ethnic minority groups, including Buryats, as expendable. In conversations with residents of Buryatia, however, PS Lab’s researcher barely encountered these attitudes. Even interview subjects who opposed the war did not bring up the issue of ethnic discrimination except in response to leading questions.

Even though we’re outlawed in Russia, we continue to deliver exclusive reporting and analysis from inside the country.

Our journalists on the ground take risks to keep you informed about changes in Russia during its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Support Meduza’s work today.

Some subjects over 30 years old lamented the fact that Buryat language and culture are gradually disappearing. At the same time, PS Lab’s researcher was surprised by how widespread Buryat words are among teenagers and adolescents, for whom knowing Buryat language and taking an interest in Buryat culture is considered “cool” and respectable. One source from Ulan-Ude said the surge of interest in Buryat culture in recent years is partially a response to the global attention on Buryatia following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Buryatia’s identity is largely state-oriented: residents generally associate themselves with the state more than with any religious or ethnic group and believe it generally represents their interests. PS Lab’s researcher observed a great deal of loyalty to state structures such as schools, universities, and local government among the people she spoke to.

Low incomes and high unemployment

The earliest investigations into the numbers of people mobilized to fight in Russia’s full-scale war in Ukraine from various regions found that a disproportionate number of draftees came from Buryatia (as well as from Dagestan, Kaliningrad, and the Krasnodar region) in 2022. As of April 2024, the republic is also one of the five regions that have lost the most servicemen to the war.

Journalists from the outlet iStories and researchers from Conflict Intelligence Team have found a statistically significant negative correlation between a region’s average income per capita and the share of people mobilized from that region (the lower the income, the higher the percentage of people drafted). Buryatia is no exception: it ranks among the ten Russian regions with the highest percentage of people living below the poverty line and is in the bottom third of regions in terms of income per capita.

To survive amid low income levels and high food prices, which sometimes exceed even those in Moscow, many Buryatia residents take out loans. Studies of creditworthiness rates across Russia have found Buryatia to be one of the country’s most disadvantaged regions in terms of per-capita debt, monthly salary levels, and cost of living. One interview subject told PS Lab that he doesn’t know anyone in Buryatia who doesn’t have loans.

Buryatia residents also compensate for low income levels by having children, as government childcare benefits have begun to exceed salaries in recent years. This dynamic exacerbates the region’s already-high unemployment rate. “We had a job opening [at the public services center], and many people, when they heard the salary, said, ‘I’ll be better off getting [childcare] benefits,” one Udurg resident said.

Despite the high unemployment level, Buryatia is also experiencing a labor shortage — which mobilization only intensified when it prompted an outflux of men from the region.

Public events and war

PS Lab’s researcher actively sought out official pro-war events to attend but had difficulty finding them. According to local residents she spoke to, many Buryatians are tired of the war and have little interest in participating in events that remind them of it. On the contrary, demand is high for events that allow people to forget about the war and other problems.

One woman told PS Lab that both artists and audiences temporarily stopped taking part in cultural activities when the full-scale war began, but that the region’s cultural life has since gradually resumed:

We were afraid [that people would stop attending events at a certain local cultural institution], but this didn’t happen. Instead, we’ve somehow drawn closer together, I would say. People don’t want to think about bad things when they come here; they come in order to relax.

A number of cultural public events were held in Udurg during the two weeks that PS Lab’s researcher spent in the village, but not a single one of them addressed military or “patriotic” issues. The same source explained that while there is a “directive from above” to hold pro-war events, she and other organizers make efforts to “neutralize this tension”: “Some people have brothers, sisters, fathers [fighting in the war]. They’re supposed to hear about it from the stage as well?”

In Ulan-Ude, unlike in Udurg, PS Lab’s researcher did manage to find some events related to the war. One of these was a party marking a young contract soldier’s send-off to the army, which his friends organized and sold tickets to. Even here, however, attendees barely discussed the war; instead, they played games, danced, and praised the future soldier for his personal qualities. The mood was largely celebratory, though when the researcher spoke to the man himself, she learned that he was less enthusiastic about his enlistment than the event’s attendees:

I asked whether he wanted to go into the army. He responded that he comes from a family of military men and that all of his older brothers are currently fighting in Ukraine. And while he didn’t say it directly, I caught the implication that he didn’t have much of a choice: “I used to really want to [join the army], but the closer my service gets, the less I want to go.”

The researcher also spoke to the man’s girlfriend, who said she has been trying to talk him out of going to war.

Throughout her regular communications with the party attendees in the days after the event, it became clear to the researcher that the majority of the soldier’s friends are against the war but prefer not to talk or think about such a “difficult” and “depressing” topic.

Volunteer efforts

While there’s no hard data on the prevalence of volunteer efforts to help the Russian military in Buryatia, most of the residents PS Lab’s researcher spoke to said that they or their relatives provide material support to the army by sending money, purchasing supplies, or making goods themselves in volunteer centers.

The researcher spent one week at a volunteer center in Ulan-Ude and three days with a volunteer group in the village of Udurg. In both cases, the volunteers handmade supplies such as camouflage nets, body armor, and cartridge pouches. Her fieldwork suggests that the following factors help explain why volunteering to help the army is so popular in Buryatia:

- Most people in Buryatia have relatives, friends, or acquaintances on the front line. For this reason, many people view sending aid to the front primarily as a form of helping their friends and family.

- Self-organized volunteer initiatives are often linked to government structures (for example, the local government might provide volunteers with a place to work or report their activities at public events), which can have the effect of the initiatives becoming “volunteer-compulsory.”

- Many people feel a sense of moral responsibility to help other community members in difficult situations.

Many Buryatia residents who take part in volunteer efforts to help soldiers don’t do so because they support the war. Instead, sending supplies to soldiers is often viewed as helping “our guys,” referring to men from Buryatia regardless of their ethnicity.

This concept of “our guys” has gradually expanded over time. One lama in Udurg told PS Lab’s researcher that while he observed many women volunteering to help their own relatives and friends at the start of the full-scale war, today he often hears volunteers make remarks like “Even if it’s not for my son, I hope [my contributions] will reach someone and be useful to them.”

The overtly political element of the war almost never came up in the volunteers’ conversations during the time PS Lab’s researcher spent with them, even though they spoke constantly while weaving and sewing supplies. On the few occasions when they did talk about the news, they focused on events in Western countries, such as the U.S. dollar exchange rate or how developments in the United States or Europe might impact Western support for Ukraine.

Occasionally, PS Lab’s researcher noted, the topic of the war would come up in the form of brief slogans or exclamations that didn’t lead to any further discussion of the topic. For example, she recorded the following moment in her ethnographic diary:

When the third stretcher was assembled, [a volunteer named] Inna said happily: “Who rocks? We rock! We’re pros!” And a minute later, totally out of nowhere, she exclaimed: “Stinking Ukes! There’ll be no mercy for you!” I was a bit shocked, though I didn’t show it, of course. Where had that come from? We weren’t discussing Ukrainians at all, and we hadn’t talked about the war for the last hour that they’d been working.

Sending money

Even more popular than volunteering to support the army is purchasing supplies or sending money to the front directly. Some Buryatians do this voluntarily, though in many cases, people feel strong social pressure to help “our guys.”

On one occasion, a woman from Udurg named Megren told PS Lab’s researcher a story about her friend who was upset after her husband was drafted. “‘Of course, I completely forgot to chip in money for our guys, didn’t I!’” the friend had remarked, according to Megren. But when PS Lab’s researcher suggested in response that Udurg residents are reluctant to speak out openly against the war because they’re afraid of repressions, Megren rejected this idea:

What repressions do we have in Udurg?! No, it’s the city [Ulan-Ude] where people are afraid. Here [in Udurg], people just want to be together with everyone else, and to not stand out from the majority.

Often, financial donations to the army are effectively compulsory; they’re frequently collected by state-funded organizations, and employees fear consequences from their colleagues or the authorities if they don’t contribute. For example, Megren, who opposes the war, told PS Lab’s researcher that a coworker once warned her she would become a “black sheep” if she didn’t make a 300-ruble ($3.40) donation to the army. The colleague later admitted to Megren that she also opposes the war but contributes to fundraisers to get others to “leave her alone.”

In other cases, citizens who strongly oppose the war nonetheless send money to the front completely voluntarily out of a desire to help their mobilized neighbors. For example, PS Lab’s researcher spoke to one anti-war family in which the grandmother had the following to say about Russia’s president:

Putin has behaved very badly. How can somebody do such a thing? Just attack Ukraine like this?

Shortly after this, however, she spoke proudly about Buryatia residents’ donations to the front:

One of my nephews is fighting in Ukraine. He was sent there in the first mobilization — they came at night and took him right from his house. Can you believe it? […] Lord, please just let him come back alive. When will this war end? […] Our village sent two, three vehicles to help the soldiers. They send food, meat, and money. […] They’re enormously helpful, our volunteer group. When it comes to this, Buryats are doing a great job, of course.

A different kind of normalization

Every person PS Lab’s researcher spoke to during her month in Buryatia had relatives and acquaintances who had gone to fight in the war, whether they were drafted or signed a contract. Every person had also either lost someone or knew somebody who had. For this reason, the war was constantly in the periphery of residents’ awareness, despite the attempts of many to distance themselves from it.

Unsurprisingly, given Buryatia’s low wages and high unemployment rate, many Buryatia residents who spoke to PS Lab talked about the war as if it were a job. Some people spoke about soldiers fighting in Ukraine as being “on shift” or “on a work trip.” Since the start of the war, it’s also become more difficult for residents to travel abroad for seasonal jobs, which also influences people’s decisions about signing army contracts.

When explaining how their friends or relatives were mobilized, PS Lab’s sources always gave one of two main reasons: either the person didn’t have a choice (he was “taken,” “ordered,” or “sent”), or he had no other employment opportunities.

Like in other Russian regions, many draftees in Buryatian villages were taken from their homes with no warning or preparation; often, this happened in the middle of the night. Many residents recalled how scary it was for them to see their relatives go in the initial period after Russia’s mobilization drive began. Over time, however, people have gotten more accustomed not just to seeing men go to war but also to soldiers’ death and funerals. One teacher in Ulan-Ude gave the following account:

At the beginning, people discussed every death and went to the funerals. I remember our boss actually making us go: “A graduate of our alma mater is being buried. Everybody is to be there tomorrow.” We didn’t even know the person. […] But now, I don’t even know who the last person to die was; I don’t hear when people die, and I don’t know how many [deaths] there have been. Whereas before, it was being discussed everywhere.

However, the gradual normalization of the war has looked different in Buryatia than it has in many other parts of Russia. While in Moscow and St. Petersburg, for example, many people have been able to continue living their lives as if there’s no war at all, this isn’t possible in Buryatia; the proximity of death has become a habitual and unavoidable aspect of daily life. As a result, many residents have begun thinking of the war not as an extraordinary event but as something routine and mundane.

Why opponents of the war don’t speak out

Buryatia’s strong horizontal social ties and their integration into vertical (administrative or political) structures have a strong influence on residents’ willingness to speak out against the war.

First of all, many residents fear that if information about their personal anti-war views falls “into the wrong hands,” it could bring dangerous consequences not only for them but for their entire family and social circle. Megren, for example, told PS Lab’s researcher that many of her friends have left Russia because they oppose the war, while those who have remained in Buryatia stay silent because they “understand what the price will be” if they speak out: “they’ll ruin you and your family.”

Second of all, discussion of the war can have a negative impact on a person’s ability to take advantage of their social ties. This is no trivial matter in Buryatia, where maintaining one’s reputation is tantamount to preserving one’s relationships and identity.

The strong role of social relationships in Buryatia has had a paradoxical effect since the start of the war: its precisely the tight-knit nature of communities there that makes people feel unable to share their own views and fears with others. One woman who works in a private hospital in Ulan-Ude described this process as follows:

Every person is withdrawing into themselves. The division in society is palpable, I’ll put it that way. Of course there are people who support all the things that are happening in our country. And there are others who don’t support it. [...] We understand that everyone is closed-off right now, and that nobody is sharing their opinion openly or trying to influence others. These are the same people who have some influence. It’s sad to observe people. But we understand why this is happening. Everyone is in a kind of internal isolation right now.

Others feel moral responsibility and social pressure not to resist the authorities’ policies even when their own life is at stake. For example, one staunch opponent of the war told PS Labs that he feels it would be wrong to leave Russia while his friends and loved ones are at the front against their will. “How would I be able to look people in the eye after that?” he said.

Additionally, in regions with strongly state-oriented identities, of which Buryatia is one, active support for the war is often less a reflection of aggressive, chauvinist, or nationalist ideas than it is an expression of residents’ desire for the state to recognize their region and its accomplishments. As a result, even when the authorities make decisions that threaten the lives of Buryatia’s residents, many people seek support and engagement from the state.

Abridged translation by Sam Breazeale