‘He wanted to belong there’ American journalist Evan Gershkovich has spent a year behind bars in the country his parents fled decades ago

Мы рассказываем честно не только про войну. Скачайте приложение.

On March 29, 2023, Wall Street Journal correspondent Evan Gershkovich was detained by Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) on espionage charges while on a reporting trip in Yekaterinburg. According to subsequent reporting from Bloomberg, Gershkovich’s arrest was personally approved by Vladimir Putin. The 32-year-old journalist is currently awaiting trial in Moscow’s Lefortovo prison, where he’s not allowed to make calls or receive visits from anyone except his lawyers. If convicted, he could face up to 20 years in prison. Six months after Gershkovich’s arrest, journalist Yulia Lukyanova profiled him for Maine’s Portland Press Herald. With the newspaper’s permission, Meduza is publishing the article in its entirety.

Update: Evan Gershkovich was released on August 1, as part of a historic prisoner exchange between Russia and Western countries. The following article was originally published on September 29, 2023.

On the morning of March 30, Olga Gladysheva tried to decide whether to buy a plane ticket from Moscow to Yekaterinburg, the fourth largest Russian city. Earlier that day Gladysheva, a 28-year-old former journalist, had learned that her friend Evan Gershkovich was detained there and suspected of espionage during a trip to the Urals for The Wall Street Journal. Russian authorities said the journalist was “collecting classified information,” and a court in Moscow, where Gershkovich was brought, arrested him. He has been jailed for six months as of Friday.

Gershkovich, 31, has almost no accent while speaking Russian. He was raised in New Jersey by Ella Milman and Michail Gershkovich, émigrés from the USSR’s Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) and Ukrainian Odesa. The couple met in Detroit, Michigan, and then settled in Princeton, New Jersey. They had a daughter, Danielle, and then Evan two years later. Evan’s nickname at home was Vanya; his sister was called Dusya. The children spoke Russian at home, ate what their mother used to cook while living in Leningrad, and watched Soviet cartoons. They absorbed both cultures — of their heritage and of a new country.

Milman, 66, and Gershkovich, 59, both Jewish, fled the Soviet Union in 1979 with the first wave of Jewish emigration. They left after the rumors that Jews were being deported to Siberia. Amid widespread antisemitism, many Soviet Jews hid their roots — they did not practice their religion or teach their children Yiddish. Milman told The Wall Street Journal her mother would shut the windows with thick woolen blankets before lighting the candles for ceremonies, so neighbors couldn’t see. Milman herself was afraid to visit a synagogue because it might give her away. (The Journal told the Press Herald that Evan Gershkovich’s parents declined to be interviewed for this story.)

The three most common destinations of the first wave of soviet Jews seeking freedom and new opportunities and trying to leave behind antisemitism and poverty were Israel, Germany and the United States. Thirty-eight years later, Evan Gershkovich landed on the ground that his parents had escaped, to write about new Russia. At that time, the country seemed vastly different from the Soviet Union.

The young journalist

In 2012, Nora Biette-Timmons was among young Evan Gershkovich’s first editors. The friends were students at Bowdoin College in Brunswick and journalists on the student newspaper, The Bowdoin Orient, where Gershkovich — an English and philosophy major — covered art. Gershkovich was “patient and grateful” while polishing pieces with an editor, Biette-Timmons says. “He was open to constructive feedback and clearly wanted to learn.”

“There can be an inclination, when you are a student, to take yourself a bit too seriously, but he was not like that,” says another Bowdoin graduate, journalist Linda Kinstler, who is also a friend and former Orient editor. “It allowed him to have fun with the columns that he was writing.” Kinstler and Biette-Timmons were among organizers of an event called “Journalism is Not a Crime” last Tuesday at Bowdoin, aimed at keeping Gershkovich’s detention in the public eye.

Biette-Timmons remembers Gershkovich playing soccer in their freshman year. A game against Amherst College went to penalty kicks. “Evan volunteered to take one, which is obviously insane and the most high-pressure thing you can do. He took one, and he made it. And he won the game.”

Gershkovich worked in a campus pub and, according to friends, was a great cook — a skill that would serve him well after an earthquake in Nepal in April 2015. Working for an environmental rights organization based in Southeast Asia after college, he went to Kathmandu to discuss climate change with rural communities. One morning he settled in a café to work when the building started shaking, he recalled in a column for the Orient. Riding out waves of aftershocks, he got to the U.S. embassy, where he spent three days without sleep, helping to cook meals for consulate workers.

After graduation in 2014 Gershkovich moved to New York and found work with a catering company, a Manhattan’s restaurant and a nongovernmental organization before finally landing a job in journalism as a temporary night clerk on The New York Times' foreign desk. Gershkovich later took a full-time assistant job there and worked for nearly two years, a period he referred to as “a form of journalism graduate school.”

A friend of his, Russian journalist Sonya Groysman, describes Gershkovich as a deep, professional and interesting person who is always there to comfort a friend. “He is very aspirational and had a clear understanding back then what he wanted from life,” she says. He applied for a position with The Moscow Times, an English-language newspaper in Russia, and in the fall of 2017 moved from Brooklyn to Moscow.

“He has always been interested in the world that his parents left behind. I think it is very common for children of parents who had to leave their homes during that era,” says Kinstler, whose parents fled the Soviet Union in 1988. However, it was not the only motivating factor for him, she believes, especially when Gershkovich found himself in “such an enriching and endlessly curious place as Russia, full of good stories to tell.”

He wanted to know what it was like to work in Russia and write about it, says Pjotr Sauer, a journalist with The Guardian who met Gershkovich on his own first day at work in The Moscow Times in 2019. They quickly became friends. “As journalists, we wished to understand Russia as best as possible,” Sauer says. Together they traveled across the country, reporting from St. Petersburg, Bashkortostan and Karelia. “The most important thing for Evan is to tell a western reader about Russia objectively, with details and without cliches,” Sauer says, “and he always looked for the stories which were not on the surface.”

“He sees his aim in showing a diverse Russia, with nuances, details, not black and white, but complex,” adds Groysman.

Russian Vanya

In Moscow Gershkovich and Sauer went out drinking, played soccer and broomball (a ball sport played on ice) on the same team, went to banya — Russian public bathhouse — and skied in Peredelkino, a small village southwest of Moscow known as a colony of Soviet first-magnitude writers. With some other foreign correspondents, they rented a wooden cottage there.

“Evan’s Moscow apartment was always full of guests,” says Olga Gladysheva, who first met Gershkovich in 2018 through other journalists. She soon found herself at karaoke, where Gershkovich “mildly lousy” sang Russian songs. “If you don’t know how to spend an evening, you would always text Evan and, if he is free, you can be sure that you will spend it together super cool and fun. At Evan’s there always would be some singing until the very morning, and it would always be Russian songs. I have never spoken English with him.”

In an interview with The Wall Street Journal, Danielle Gershkovich said that after moving to Russia her brother told her he had understood certain nuances of their parents’ words better than while they were growing up. When they were kids, the siblings often visited their grandparents on Brighton Beach in New York, a place that Evan Gershkovich called “a little Soviet Union, stuck in time,” and a time machine that could transport a person into movies about the USSR. Now, he had an opportunity to explore modern Russia.

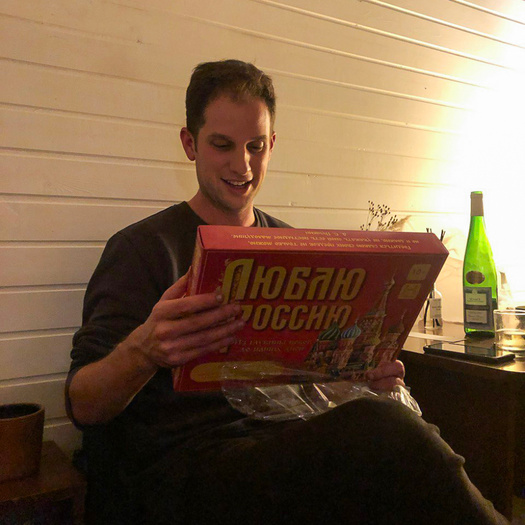

According to Gladysheva, Gershkovich would call himself “Russian Vanya.” She thought of it as one of his jokes until a common friend told her that he feels aggrieved when called Evan. “I asked him if he was truly offended by it, and he responded, ‘Yes. I think Russians should call me Vanya,’” says Gladysheva. “He wanted to belong here.”

While speaking about the differences between Russia and the United States in a BBC podcast, Gershkovich said he barely sees any differences. “I do not differ people in the provinces of Russia and the US — except they watch different YouTube shows and believe in different conspiracy theories.” Being fluent in both cultures, Gershkovich thought that he could bridge the gap between two countries, says journalist Jeremy Berke, a fellow Bowdoin graduate.

“When you start reporting in Russia, you often hear that it will be very hard to get people to talk,” Gershkovich told a Bowdoin College website in an interview in the summer of 2020. “And while that may be true of Russian officialdom — though not all of it — I have found that if you go looking for the right people, many of them want to tell their stories.”

The Kremlin’s tail

At The Moscow Times, Gershkovich reported on Russians struggling to receive medical help in the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, covered people protesting the arrest of a governor in far east Khabarovsk, and wrote about ethnic conflicts in the Volga region. He then reported from Moscow for Agence France-Presse and in January 2022 joined The Wall Street Journal. He had dreamed about working for a big American newspaper, says Pjotr Sauer. There Gershkovich would work on five stories at the same time. He covered a wide range of Russian topics, from human rights to the war in Ukraine, says Sonya Groysman.

On Feb. 24, 2022, when Russia started its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Biette-Timmons texted her college friend and asked how he was. Gershkovich was in London, preparing to join The Journal’s Moscow bureau.

“Oh, it's okay,” he answered. "I am just sad and sleepless, but holding on. Thanks for the message, hope you are doing okay.”

“You are reporting the war, it does not matter if I am okay!” exclaims Biette-Timmons while reading out the message.

A few days later another friend from Bowdoin, Jeremy Berke, asked Gershkovich if it was safe in Moscow. “I can’t even work in a country right now. I think it’s over,” responded the journalist.

In February, when the already harsh Russian censorship strengthened, many of the country’s journalists fled in fear of criminal prosecution. The Journal decided that Gershkovich should reside in London but would let him travel to Russia for reporting. He perceived London as a transit point, says Gladysheva, and planned to move to Berlin, where his friends, including exiled Russian journalists, found a new home. Pjotr Sauer remembers Gershkovich saying he would travel to Russia for reporting as long as he would be permitted to enter.

Both Groysman and Gladysheva note that by the time Gershkovich joined The Journal he had acquired sources who would have spoken reluctantly even with Russian journalists. “I learned more about how Russian authorities think from his pieces rather than pieces of my Russian colleagues,” Groysman says. Most Russian journalists had lost access to well-placed sources, and the Kremlin cared more about what was reported in Russian than English, Pjotr Sauer says. Still, foreign correspondents’ accreditations, granted by Russian authorities, carried only the illusion of safety.

“Evan was questioned a lot on the border,” Berke says, “but they have never stopped him from doing anything.” Berke remembers a conversation he and Gerskovich had in 2022, when the latter briefly came to New York. They discussed the “immense challenges” reporting in Russia. “‘So we just continue doing what we were doing,’ Evan said”, Berke adds. “He was not scared.”

Foreign correspondents are accustomed to being followed, says Sauer, and all of them saw it as a part of a job, an attempt of Russian authorities to scare them. Olga Gladysheva heard from Gershkovich that “when you come on a trip in the regions, you definitely have a tail.” Even so, Gershkovich would always act openly. “It was substantial to him that they would know where he was, what he was doing, for not accuse him later of hiding from someone,” she says, “because he was doing legitimate journalistic work.” She remembers them discussing the possibility that Gershkovich could be accused of espionage. “I said it surely can happen, but what a terrible thing you should do to get accused?”

A high-profile hostage

On March, 29 The Wall Street Journal lost track of its Russia reporter. He had been checking in with the newspaper hourly, mostly via text, but suddenly stopped responding. At the same time Michail Gershkovich, who also hadn't heard from his son, reached out to Pjotr Sauer and asked if he knew where Evan was.

The news that Gershkovich had disappeared started to spread. The next day Russian authorities accused the journalist of espionage — punishable by 10 to 20 years imprisonment — and released a photo in which Gershkovich, wearing a yellow jacket with a hood, was escorted by men in civilian clothes. (Neither Gershkovich’s lawyers nor The Wall Street Journal would answer the Press Herald’s questions.)

Nobody had tailed Gershkovich and a freelance photographer for the Journal, Patrick Wack, during a previous trip to Yekaterinburg and Nizhny Tagil in the middle of March, Wack says — either that or they hadn’t noticed it. “We were surprised how smoothly everything went,” Wack says. After the two journalists returned to Moscow, Gershkovich decided he needed more information for his piece and flew to the Urals again — this time alone. Although Wack prefers not to discuss the subject of the article they were working on, both cities they were in are famous for weapons and tank factories.

No one, including a lawyer who had been quickly found by Gershkovich’s friends, was allowed to attend the journalist’s hearing. The judge decided that Gershkovich would be held in the Lefortovo pre-trial detention center — used for high-profile criminals, such as former ministers, and those who were accused of spying or treason — until the end of May. He has been held captive there since.

The U.S. State Department has designated Gershkovich as “wrongfully detained,” and President Biden has said the U.S. continues to press Russia to release him and is “serious about a prisoner exchange.” Dmitry Peskov, spokesman for Russian president Vladimir Putin, denied reports that Putin authorized Gershkovich’s arrest. “It is not the president’s prerogative. The security services do that,” he said. “They are doing their job.”

Gershkovich’s friends quickly mobilized an effort to secure his freedom. “I just reached out to anyone I possibly could,” Jeremy Berke says. “In the first couple of weeks we were working 24/7 just to figure out if we can help in any way. That involved reaching out to Evan’s parents, his sister, figuring out what they needed, reaching out to the State Department, to the federal and state officials in the U.S. to see how they can help us, and talking to the Journal.”

The group, consisting mainly of journalists, connected with the Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs (SPEHA), a team in the State Department that conducts hostage negotiations. “They were very, very helpful, took it very seriously, and would answer our calls and messages any hour,” Berke says. SPEHA told family and friends that they should brace themselves, as the process of trading for Gershkovich will not be fast, he adds. Meanwhile, the Journal removed its employees from Russia after Gershkovich’s arrest. Wack also left Russia.

Russian authorities don’t allow anything in foreign languages into prison, so Gershkovich’s friends gather the English-language letters to him and then translate them into Russian. Olga Gladysheva then prints them out and mails them from a post office near the detention center, so the letters can arrive at his cell as soon as possible. Every week, she says, she sends letters from nearly 50 people. Gershkovich is not allowed to make calls or have visits, except for lawyers. He shares a cell with another prisoner, but he has not told Gladysheva why his cellmate was arrested. “At least, he does not snore,” says Olga.

“It’s ridiculous to suggest that Evan is a spy,” Gladysheva says. “He’s a dude who loves to gossip. That’s why he is a great friend. Thanks to him, you learn a lot of information.” Now the friends are providing Gershkovich with all kinds of information, including gossip, NBA scores, HBO’s “Succession” spoilers, news stories, book reviews, and reminders of why he is such a good friend. Some of them use pseudonyms when writing to him. “It’s pretty bizarre to have Evan as pen-pal,” Berke says.

Sonya Groysman says Gershkovich has been reading Russian literature during his six months in captivity. “He even read ‘The House of Government’ by Yuri Slezkine as well as ‘And Quiet Flows the Don’ by Mikhail Sholokhov!” Gershkovich’s letters, says Groysman, are perceived by her as the real literature. Groysman herself is rereading “The Anna Karenina Fix: Life Lessons from Russian Literature,” a self-help memoir by British writer Viv Groskop. She does it to answer Gershkovich’s questions about books he is reading in a cell. “In fact, Groskop’s analysis comes down to a piece of advice: ‘Don’t be discouraged, no matter what the situation is,’" Groysman says. “This is taught by many works of Russian classics: how not to become discouraged in any situation. Or, if you still get discouraged, then how do you do it with taste.”

It seems those lessons do work. Olga Gladysheva, who also organizes a delivery to Gershkovich, including food, complains about his whims with a smile: “‘Olga,’ he wrote to me the other day, ‘you fed me up with doctorskaya sausage. Could not you send me some prosciutto?’”

Story by Yulia Lukyanova

Published by permission from Portland Press Herald