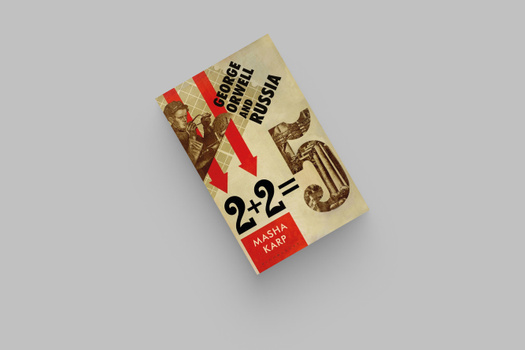

Between socialist promise and totalitarian threat Owen Boynton reviews Masha Karp’s ‘George Orwell and Russia’

Мы говорим как есть не только про политику. Скачайте приложение.

In his two most famous novels, “Animal Farm” and “Nineteen Eighty-Four,” the lifelong socialist George Orwell cautioned his readers, chiefly conceived to be the British leftists, about the dangers of totalitarianism they had to take into account if they wanted to secure a more just and equal future for the working classes. In her new book, “George Orwell and Russia,” Masha Karp — an Orwell scholar and Russian Features Editor at the BBC World Service — explores in depth George Orwell’s political views, the Russian roots of his novels, and the way Orwell himself had been drawn into the propaganda struggle between Britain and the Soviets when he found himself composing the controversial “Orwell’s list” of 1949. Owen Boynton reviews Masha Karp’s book, finding a great deal to admire, but taking issue with parts of the author’s moral argument about Orwell.

Whatever ups and downs his reputation may have undergone, George Orwell has never gone out of fashion. It isn’t just Nineteen Eighty-Four that persists in our cultural imagination. Orwell’s essays (“Politics and the English Language” and “Shooting an Elephant” especially) are mainstays of curricula in the English-speaking world. Animal Farm is taught in English classes even as the Russian Revolution that inspired it has been pushed aside in the history classroom. The brisk clarity of Orwell’s style and his independence of mind, cocky in argument and humble in self-awareness, are exemplary as a measure of sound English prose. His rules of thumb for sane and honest writing remain exceedingly helpful for any writer, difficult as they might be to follow in practice.

This continued appeal is somewhat surprising, given how topical much of Orwell’s writing is: its local skirmishes, cultural reference points, and political urgency are often matters of distant history to today’s reader. Still, Orwell had the talent for rooting out what really matters; he had a nose for the nub of things. And when those things have a habit of sticking around, Orwell’s words and his sense of those things also stick.

Unfortunately, as Masha Karp’s new book George Orwell and Russia argues, one of the persistent phenomena that has recently made Orwell relevant anew is autocracy. Sustained by the old totalitarian habits, it has resurfaced and spread in Putin’s Russia. The title of Karp’s book refers to what Russia meant to Orwell over the course of his life, what Orwell meant to Russia during and after his life, and how Orwell matters if we are to understand what is happening in Russia now. It is probably a book for readers who have some familiarity with Orwell’s work; but if they don’t, the last two chapters, on Orwell and Russia under Putin, will lead the reader back to his words.

Given that Orwell’s two most famous novels, Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm, are directly inspired by Soviet Russia, and totalitarian Stalinist Russia especially, the subject of Karp’s book is obvious. At the same time, because Orwell lived and wrote in the shadow of Soviet Russia, it is challenging to decide where the Soviet presence matters, and where it doesn’t: it’s so diffuse as to be elusive. Karp might have painted her study in broad brushstrokes, drawing conclusions from readings of essays and paraphrases of Orwell’s statements. Instead, she relishes the details of exactly how, when, and what Orwell would have learned about Soviet Russia, and how his attitudes towards Russia changed over time, especially in relation to his continued belief in the ideals of socialism. Sometimes, she focuses on the political history around Orwell, sometimes on biography, and sometimes on tracing his ideas and art. Though at times the forest is lost for the trees, her book is most impressive on account of how judiciously she selects her material, erring on the side of factual accuracy and abundance.

Born Eric Blair in 1903 (he would only adopt the pen name “George Orwell” in the early 1930s), Orwell attended Eton from 1917 to 1921. With the Russian Revolution half a world away, we have records of his joining his Eton peers in celebrating the revolutionaries. Karp’s story, though, takes as its true beginning Orwell’s stay with his Aunt Nellie in Paris, in the late 1920s.

Nellie was devoted to the cause of Esperanto, the artificial language constructed in the late 19th century in hopes of unifying humankind through a common tongue not attached to any historic nation. Looking back on the intensity of Esperanto’s advocates in the 1920s is both humbling and bewildering: they couldn’t have known how irrelevant their aim would be to the changes they helped bring about. Because of their global ambitions, many Esperantists participated in the global socialist movement. Some of them traveled to Russia in the 1920s, eager to see what the Revolution had wrought. The Esperantist leader Eugène Lanti was one such traveler. He was also Aunt Nellie’s future husband, and was already her partner during Orwell’s stay. It’s hard to believe, Karp writes, that Orwell would not have heard rumblings and grumbling about the state of affairs in Russia in conversations around Nellie’s Parisian apartment, since Lanti had been in Russia a few years prior and was in contact with associates still there.

By the early 1930s, Orwell was living in Britain, his Aunt Nellie’s friend Mynfawny Westrope both his landlady and occasional employer. Like Nellie, she was a committed socialist, and in her circles, which included the leading British Trotskyite Reg Groves, Orwell listened and joined into the debates of the British Left. Westrope was friends with more people like Lanti and his fellows, who had suffered first-hand disillusionment in Soviet Russia. It was here that Orwell saw a set within the British Left insisting on the validity of its ideas about what ought to be the case, rather than looking squarely at the available testimonies of what the situation in Russia was actually like. He did not speak out, or publish, much of what he was revolving in his head during the first half of the 1930s. The release, when it came, took the form of his wanting to see for himself — not the Soviet tragedy, but the lives of the working classes in Britain. His time in the North of England led him to come to terms with Socialism, as a necessary promise and potential threat.

But it was in Spain that Orwell experienced first-hand the reach and feel of Soviet power, and it turned him against Communism for the rest of his life. Although his habit of mind was to question all things relentlessly, he did not question that language ought to be a trustworthy, if imperfect, instrument. He was horrified by those who degraded it by eviscerating its meanings and social functions. The Soviet regime under Stalin depended on such degradation, like any totalitarian or autocratic state, along with the simultaneous degradation of the individual spirit. Karp’s chapter on the Spanish Civil War seemed to me a bit gummy with details about what was admittedly an extraordinarily complicated conflict, involving, importantly for Orwell, clashes between different leftist groups. By describing the political machinations Orwell faced in Spain, Karp prepares to justify the claim that “Orwell’s understanding of the fear a human being feels when faced with a huge, ruthless, inhuman power was born in Spain, where he suddenly found himself under the arbitrary rules of an oppressive regime.”

Upon his return from Spain, Orwell read and reviewed widely. Karp superbly draws attention to two authors whose writings mattered greatly to Orwell, especially in the years when Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four were germinating: Franz Borkenau and Arthur Koestler. The former wrote about the Spanish Civil War and about the rise of the totalitarian state from the perspective of a social scientist, with moorings in the Frankfurt School. Koestler’s Darkness at Noon was the only novel about Russia that Orwell reviewed. Karp shows how both of them deepened his understanding and imagination. “One of the most conspicuous features of all Orwell’s writings about Borkenau,” she observes, “is his almost subconscious translation of Borkenau’s sociological concepts into images and then developing these images.”

Though consistently sympathetic to socialism, Orwell came to be considered suspect in some quarters of the British Left as his opposition to Stalin and the Soviet state grew in volume and intensity. Then, as Europe lurched into a Second World War, Orwell’s anti-Soviet position became suddenly popular when Nazi-Soviet pact was struck in 1939, only to veer into new extremes of unpopularity when the Soviets joined the British in opposing the Nazis. Even during the war, Orwell remained suspicious of Soviet propaganda, now bolstered by successes on the battlefield and acts of courage that he himself admired as much as anyone else.

In 1943 and 1944, Nineteen Eighty-Four was germinating in notes and Animal Farm was being sent around for publication. Orwell’s sense for the rotten odors on the breeze was as keen as ever. Animal Farm would prove especially difficult to publish. It was opposed by a highly-placed Soviet agent, Peter Smollett, who oversaw the Soviet Relations Division at the British Ministry of Information while in active communication with the Cambridge spies Kim Philby and Guy Burgess. Nevertheless, in 1945, Orwell’s novel was finally published. Though it was selling well and receiving praise, even critics friendly to Orwell scolded the book for taking aim at the Soviets, or else suggested that the book’s targets were things of the past. Like many great allegories, it exceeded its occasion: the Soviet figures on which its characters are based seem themselves to be examples of the larger types that it creates. In her pages on Orwell’s most enduring and memorable novels, Karp is at her best, leading us nimbly through the worlds of publishing and politics.

She is also superb on the genesis of Nineteen Eighty-Four, tracing its debt to the Russian author Yevgeny Zamyatin. Orwell had begun planning his novel before reading and reviewing Zamyatin’s We, but his encounter with that 1923 dystopian fantasy sharpened his understanding of what he was trying to accomplish in his own novel. Unlike Zamyatin, who had to imagine totalitarian horrors not yet made real in history, Orwell had events in Russia on which to draw. In the post-war years, more and more of the British were waking up to the realities of Soviet totalitarianism, and Orwell found some real success in consolidating a coalition of writers, communist and otherwise, to oppose it. Karp quietly takes on those who, nowadays, are quick to dismiss such coalitions as stooges for American interests and the CIA, who would eventually fund their activity. Doing so, she argues, underestimates their freedom of mind and unfairly ignores their diversity of political hopes. Orwell, for instance, returned repeatedly to a dream of a United Socialist States of Europe.

Karp’s book is divided into two parts. Though the reason for the division is not especially clear, the second part is more argumentative and polemical than the first. One section is worth exploring in some detail, since it shows a limitation of Karp’s admiration for her subject.

In 1949, Orwell wrote to his friend Celia Kirwan, employed at the British Information Research Department, founded in 1948 to counter Soviet propaganda; in his letter, he named 38 British intellectuals he believed to harbor pro-Soviet sentiments that would make them unreliable to help the IRD. Karp explains that Orwell thought the threat was real, did not want (as he explained) to have someone like Peter Smollett in a position of power, and felt that in general the British intelligentsia remained hoodwinked by the Soviet state. They could not or would not see what was happening, and he didn’t want Kirwan to be in the same position. At the time, Orwell wrote of his list of names, “It isn’t very sensational and I don’t suppose it will tell your friends anything they don’t know.” But the names were not all: Orwell identified individuals on the list with labels (including “Jewish” and “occasionally Homosexual”) as well as assessments of their individual probity.

The existence of the lists and some of the names were revealed in 1991, and then, in 1996, as more came to light, there was a public (posthumous, obviously) outcry. Some accused Orwell of betrayal, others of hypocrisy. There is even now a Wikipedia article on “Orwell’s list.” Orwell’s editor Peter Davidson has suggested that the labels may have been Orwell’s attempt at identifying potential facts about individuals that might have been exploited by Soviet agents. It might even, he speculates, have been motivated by Orwell’s abiding interest in psychology and politics.

Karp approves Davidson’s theory. “Considered in this light,” she writes,

Orwell’s comments in the list stop being ‘smears’ applied by him to different people but become private pointers for the writer, who honestly, humanely and without prejudice tried to see their motives and predict their behavior.

This language exonerates recklessly. After all, if the labels really are “smears,” then they obviously do betray prejudice and bigotry, and if they are not (as “Jewish” and “occasionally Homosexual” are not), then it seems a distraction to raise an accusation that isn’t to the point.

Admittedly, the list was written in a private journal; all we can do is speculate. But uncertainty forbids the strong defense that Karp attempts to mount and which comes across as decidedly peculiar. I’m not sure how we can say the list reflects Orwell’s “honesty” at all, when we don’t know what Orwell even thought he was doing. We can’t say he wrote it “humanely” unless we think it is humane for Orwell, the stalwart defender of individual judgment, to decide that he paternalistically needs to keep tabs on his fellow citizens. “Without prejudice” is strangest of all: if Karp and Davidson are correct that Orwell wrote the list as part of a study in psychology and politics, then it must have been written with a great deal of thought about prejudice, and the terms themselves offer no diagnosis of that prejudice, but depend upon implying a great deal of it. Finally, why would Orwell have thought, even if he did believe there was a threat posed either to or from those on his list, that it was his place to work against it by amassing short-hand files on potential enemy agents? At best, the list raises questions that cannot be satisfactorily answered; it certainly doesn’t warrant exorbitant praise. Orwell deserves to be stood up to; his distrust of saints warrants our refusing to impute righteousness to all that he did himself.

More often, Karp embraces and enters into the contradictions and conflicts in Orwell’s own mind. In his views of socialism, the subject of her seventh chapter, he was perpetually perplexed. In a passage that deserves extensive quotation, Karp writes:

The way Orwell dealt with his hesitations about socialism does speak to our time. He remained split because he could not abandon either his hope for a better future of mankind, which his time had taught him to call socialism, or his capacity to see things as they are. Nobody could call him cynical and yet he refused to be deluded himself and tried to warn others against their delusions by depicting horrifying consequences of socialist dreams.

He did not abandon the promise of those dreams. When looking for a publisher and translator for Animal Farm, he explained that he hoped the novel could be “essential for a revival of the socialist movement.” Though he never found out, he would have been disappointed that the first Slavic edition, a Ukrainian translation, was published by those who had no sympathy for the motivations behind the Russian Revolution.

Karp’s book benefits from being many things, from chapter to chapter, and even from paragraph to paragraph. Beyond politics, literary history, and biography, there is (in the eighth chapter) detective work on the Russian publication history of Nineteen Eighty-Four, which went through several editions from 1956. Fascinatingly, a 1959 edition of the novel was translated and prepared for the upper echelons of the Soviet government, supervised by the KGB, to keep them abreast of what they recognized as a potentially devastating piece of propaganda. Only in the past few years has one of the two translators been identified. An entire network of publishers covertly distributed foreign editions of Orwell’s novels into Russia from abroad during the 1960s and 1970s; others translated, copied, and disseminated them once they were in the country.

In 1988, both Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four were officially published in Russia for the first time. Writing on Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer in his essay “Inside the Whale,” George Orwell described the feeling of reading a book that “opens up a new world not by revealing what is strange but by revealing what is familiar.” Karp’s ninth chapter explores what this meant for generations of Russian readers holding Nineteen Eighty-Four in their hands, recollecting the Great Terror, the betrayal of parents by children, the routines of surveillance, and the fragility of human life under totalitarianism.

But her book does not end there; instead, it culminates in a final chapter that argues that it has been a terrible mistake to think Orwell’s warnings against totalitarian Soviet state a relic of the 20th century. Orwell coined the phrase the “Russian myth” to name the fantasy about Stalin and Soviet Russia to which many British liberals acquiesced. Karp suggests a new “Russian myth,” to which this generation of European and American intellectuals has been subject, arose in the 1990s, following the fall of the USSR. In that myth, Russia had completed its transformation into a liberal capitalist democracy. Now, in 2023, Karp argues, we see that totalitarian statecraft was neither eviscerated nor entirely left behind. With Putin’s war in Ukraine, his erasure of the past, and his punishment of dissident voices, Orwell is sadly familiar once more. Characteristically, he never lost sight of us.

Owen Boynton is director of strategic initiatives and an English teacher at Collegiate School in New York City. His articles and reviews have appeared in Essays in Criticism, Victorian Poetry, Romanticism, Literary Imagination, and The Chaucer Review. More of his literary criticism can be found on his website, Critical Provisions.

Owen Boynton