‘We can do it again’ The invention and reinvention of an ‘antifascist-fascist’ slogan

Мы рассказываем честно не только про войну. Скачайте приложение.

The Second World War was a transformative, foundational event for the Soviet Union. When the Red Army captured Berlin in May, 1945, it signaled victory over years of massive, widespread suffering and death among soldiers and civilians. In the years leading up to Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, certain aspects of the Second World War acquired special symbolic significance in Russia, which has positioned itself as the “owner” of that period’s legacy. Russian Victory Day, celebrated every year on May 9, gradually transformed from a day of quiet remembrance for fallen veterans into increasingly lavish saber-rattling spectacles. Pro-Putin propagandists, and eventually Putin himself, began speaking of the need to “de-nazify” Ukraine — this would become one of the main justifications for the invasion. And a World War II-era slogan, “We can do it again,” appeared as a popular evocation of both the sacrifices previous generations made to defeat Nazi Germany and the contemporary Russian chauvinism that fuels the war in Ukraine. Meduza explains the origins of the phrase “We can do it again,” and how it was transformed from a celebration of dignity and sacrifice into a symbol of aggressive nationalism — and a lewd bumper sticker.

The following essay was adapted from an edition of Signal, Meduza’s daily newsletter about histories and ideas that can help us understand today’s news. You can subscribe to Signal (it’s in Russian) here. English-language version by Emily Laskin.

In April 2022, Maia Sandu, President of Moldova, Ukraine’s western neighbor and a fellow former Soviet state, spearheaded a campaign to ban three of the most recognizable symbols of Russian militarism — the Latin letters V and Z, and the orange-and-black striped St. George ribbon — in her country.

Discussing the new legislation, she alluded to one more symbol of Russian militarism, saying: “‘We can do it again,’ — no. ‘Never again,’ — yes.”

Both phrases, “We can do it again,” and “Never again,” refer to the Second World War, though they share little in terms of cultural significance. And Sandu is far from the only public figure to put the two phrases in opposition to each other. In May 2022, in a blog post for the Federation Council website, Russian Senator Nikolay Fyodorov wrote, “Do what again? Nearly 27 million of your compatriots dead on the battlefield and at the home front from hunger, cold, and disease?” He added that veterans like his father used to tell their descendents “‘We fought for peace. So that there would be no more war.’ Then they would quietly add, ‘Never again.’” The writer Dmitry Glukhovsky referenced, in an interview with Meduza “antifascist-fascist slogans,” nodding to the way that a certain segment of Russian society has repurposed one originally sober response to the tragedies of of World War II.

The phrase “Never again,” whose use extends far beyond Russia, functions as a promise to prevent another Holocaust and, by extension, new genocides and wars. More than a few people consider the sentiment unrealistic. Still, there’s no doubt that it’s said in the spirit of benevolent hope.

The meaning of “We can do it again” is less obvious.

Where it comes from

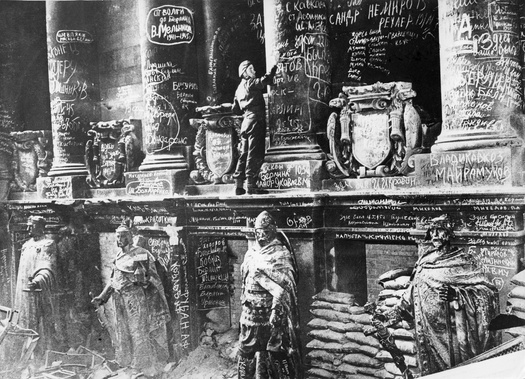

The probable origin of “We can do it again” is a piece of graffiti left by an unknown Soviet soldier on wall of the Reichstag in 1945:

“For the raids on Moscow. For shelling Leningrad. For Tikhvin and Stalingrad. Remember, and don’t forget. We can do that all again.”

The original phrase featured a non-standard spelling of the Russian word povtorit, “to repeat” or “do again.” The graffiti on the Reichstag wall read podovtorit — not a spelling error, but a form characteristic of the north-western Russian dialect. Evidently, the man who wrote the slogan was himself from Tikhvin or its outskirts in the Leningrad region. In 1941, the city saw heavy fighting (first defensive, and then an offensive by the Red Army), and Tikhvin was occupied for a month.

Soviet soldiers left many similar phrases on the Reichstag walls: “Hey Hanses and Fritzes! You’ll never forget this! And if necessary, we’ll come again,” or “We came to Berlin, sword in hand, to turn the Germans from the sword forever” (the latter has been preserved).

In 1955, the poet and frontline veteran Mikhail Dudin composed a soldier’s song for the film Maksim Perepelitsa, which features the couplet:

Let the enemy remember:

We’re not threatening, just saying.

We’ve crossed half the world with you.

If we have to, we’ll do it again.

People who lived through the Second World War well understood the difference between threatening and “just saying.” Fighting again was likely the last thing they wanted.

In the end, “We can do it again” completely disappeared from the “canon” of Soviet war memory, which was already taking shape by the 1960s. In its place, another idea had prevailed: “Just let there be no war.” The probable source of that phrase, which became the Soviet version of “Never again,” is the 1959 Alexander Volodin song, “Pyat Vecherov” (“Five Evenings”).

Rebirth of a slogan

The big question is whether “We can do it again” has returned or has been “invented” again. In either case, its meaning has changed since the 1940s and 1950s.

Bumper stickers with the words “We can do it again” started to appear on cars in anticipation of May 9 (Victory Day), 2012. They were the brainchild of a Moscow designer who prefers to remain anonymous. He says the first version had no words — it was just a figure with a hammer and sickle for a head raping a figure whose head is a swastika.

The designer insists that he categorically dislikes the drawing: it’s “crass,” “trashy,” “what’s there to be proud of there?” But, somehow, the image was selected for an exchange with other sticker makers. Then someone posted it on the entertainment and news site Fishki.net (which is akin to a Russian Reddit). The sticker’s popularity exploded in the spring of 2014, against the backdrop of the annexation of Crimea and war in the Donbas — by this point, the slogan “We can do it again” had appeared on the sticker, alongside the original image.

It’s not clear who added the slogan, or when. It’s also not clear that the slogan was an intentional homage to the Reichstag graffiti, which is not even the most famous of the phrases written on the Reichstag walls. (It’s much less well-known than, for example, an inscription that reads “Satisfied with the ruins of Berlin,” which was featured in the celebrated Soviet war drama Only Old Men Are Going to Battle.) What is clear is that it’s been revived and refashioned in the last decade to express a growing resentment about the West’s failure to recognize Russia’s status as a great power, and its “oppression” and “humiliation” of the country. In 2018, journalist Pyotr Akopov called the phrase’s new meaning “a protective reaction to the external pressures Russia is facing.”

In this sense, “We can do it again” has become an important aspect of the past two decades’ “reinvention” of Victory Day. The holiday was previously primarily a memorial for veterans. Many still remember that as the holiday’s “proper” format. (For example, the actor and television host Dmitry Nagiev, who said derisively in an interview, “What is that? Who do you think you are that you want to do it again? I remember going to Victory Day celebrations with my grandfather when it was just old men drinking quietly.”) But there are fewer living veterans every year, although authorities keep expanding who has the right to veteran status. Under Putin, Victory Day has gradually become geared toward younger crowds.

The trend is not unique to Russia. When most World War I veterans in the UK had passed away, British authorities made November 11, the anniversary of the war’s end, into a national Remembrance Day. Its most famous symbol is a red poppy, which Britons pin on their clothes as a sign of respect for departed veterans. The striped St. George ribbon appeared in Russia on the 60th anniversary of Victory Day, in 2005. Five years later, on the next major anniversary, the slogan “Thanks, grandad, for the victory,” appeared, and people began to decorate the walls of homes in cities with images of an eternal flame (commemorating the Soviet soldiers lost in the Second World War), carnations (traditionally for funerals in Russia), and the St. George Ribbon.

Journalism saves lives. Help Meduza continue its mission.

In times of war, people's lives often depend on access to reliable information. Meduza is a trusted news source for millions of readers in Russia, Ukraine, and beyond. By helping Meduza, you’re helping these people stay informed during these tough times. Please, support our work.

As in the UK, the holiday became more inclusive: you no longer had to have taken part in or witnessed combat to feel that the holiday was your own. But that’s where the similarities end. The UK unites in November in sorrow; Russia unites in May in triumph. The collective hero of May 9 in Russia is one victorious people, a “collective body” that includes veterans and their descendants. Wear the St. George ribbon — declare that you’re part of the victorious people — and you’re automatically involved in the most brutal sacrifices that the war required. It’s as if the writing on the Reichstag wall was your writing, and the defeat of nazism your own achievement.

A soldier who had just gone through hell and captured Berlin with his own hands could write “We can do it again” on a sooty Reichstag wall with a feeling of personal dignity. His descendant, who puts a sticker with the same slogan on his car, acquires dignity by dissolving into the “collective body” of the victorious people.

Lev Gudkov, director of the Levada Center, Russia’s only independent polling operation, said back in 2018 that for contemporary Russians, belonging to a great power is “symbolic replenishment for the small person’s everyday feeling of constant humiliation.”

That feeling of humiliation and “political grievance” is referred to in philosophy as ressentiment. The German philosopher Max Scheler described ressentiment as a complex of emotions, which a person cannot help but experience, but which he represses as “low” (malice, envy, vindictiveness, and so on). It could be, for example, a poor man’s envy for a car that a rich man is driving — a very understandable feeling, but not a “respectable” one. Such emotions can be expressed through a free press, parliamentary government, and other political tools. But if they are simply banned, there is a danger that an alternative value system will develop. This alternative system is built on the rejection of hypocritical “high” emotions and an embrace of “authentically populist” or “low” ones.

This is evidently the state of affairs that has developed in Russia. And the vicious “We can do it again” is its a concentrated expression.

How the government employs the phrase — or avoids it

It seems like authorities didn’t have a real grasp on how to relate to this phrase when it became popular — they were in no hurry to use it as a slogan.

In 2020, as part of a TASS project “20 Questions for Vladimir Putin,” interviewer Andrey Vandenko asked the president how he felt about the phrases “Thanks, grandad, for the victory!,” “To Berlin!,” and “We can do it again.” The president approved only of the first, and of the last he spoke carefully, saying “If anyone dares to do anything like that [the nazi attack on the USSR], we’ll do it again.” So, he said essentially what was said after the Second World War. Morever, Putin would only actually say “Thanks, grandad, for the victory.” Rather than uttering “We can do it again,” he said “the slogan you were talking about.”

Lev Gudkov, of the Levada Center, has said that although Russians value their great-power status, this only rarely translates into outright militancy. A militant stance is most characteristic of a relatively small group of aggressive, reactionary people (who are, as a rule, men). Such attitudes are most pronounced in “groups that feel their own dependence and humiliation most acutely,” the sociologist explained. Gudkov estimates that at the peak of its popularity, only around 12 to 14 percent of Russians supported the slogan “We can do it again.”

Nonetheless, Russian authorities have not spoken out directly against the slogan — for example, they haven’t condemned it as a call to a war of aggression, which is prohibited by the Russian criminal code. And it has probably played a role in a more general militarization of Russian consciousness.

It became clear in February 2022 that the “reactionary, aggressive minority,” as Gudkov calls it, who support the sentiment behind “We can do it again,” exerts outsized influence in Russia. Even at the historic meeting of the country’s Security Council, just days before the invasion of Ukraine, authorities were not united in support of war — some participants cautiously supported continuing negotiations.

Russians who support the war in Ukraine argue that Ukrainians “squeeze,” “oppress,” and “hate” Russians. Putin has publicly distanced himself from the slogan “We can do it again,” but his speeches on February 21 and February 24, just before and just after the war began, were dripping with ressentiment — a vengeful animosity for Ukraine and the entire world for “ingratitude,” “misunderstanding,” and “infringement” of Russia, for ignoring its interests and not recognizing its greatness.

What, exactly, the aggressive minority desires to “do again” is plenty clear from the bumper stickers. After all, they don’t depict raising the flag of victory and peace over the Reichstag, but rape — an assertion of unconditional superiority and possession.

Postscript

Much of the Soviet graffiti originally left on the Reichstag walls remains there to this day. Some has been preserved and hidden under plaster, and some is on display alongside translations. German politicians occasionally float the idea of getting rid of it. A proposal to that effect made it to the Bundestag (which meets in the former Reichstag building) in the early 2000s, but it was rejected.

During the reconstruction of the Reichstag in the 1990s, Germany removed some of the lewdest phrases, with the agreement of the Russian Embassy to Germany.

Story by Meduza

English-language version by Emily Laskin