‘There’s plenty of idiots on both sides of the Atlantic’ The decline of Skoltech, Russia’s cutting-edge research institute that once partnered with MIT

Мы рассказываем честно не только про войну. Скачайте приложение.

Reported by Svetlana Reiter. Translated by Anna Razumnaya.

“Skoltech” is the shorthand for the Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology — a project started by Dmitry Medvedev during his presidency, when he was still enchanted by the West and wanted Russian science to be an equal player vis-à-vis Silicon Valley and other global centers of innovation. As an emblem of this ambition, Skoltech enjoyed lavish government funding: in its decade in existence, the research institution managed to spend $400 million just on partner projects with Boston’s MIT. With the start of the Ukraine war, though, faculty and students began to leave Skoltech in droves. U.S. sanctions have been devastating for the once-vibrant school and its programs. Meduza special correspondent Svetlana Reiter spoke with former members of Skoltech’s moribund scientific community, most of which is now scattered across the world. Many of them have fond memories of doing research at Skoltech and speak of its decline with genuine regret.

‘I missed them all in advance’

Daniil Vygovsky was at his lab when he first heard that Russia had launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The 26-year-old Skoltech grad student was struck by his lab-mates’ lost and frightened expressions. “I’d never seen them in a state like that,” he says.

Vygovsky was born in Kyiv. His first response to the news was to “maximally isolate” himself from disturbing information. He stopped talking to anyone except family and friends from grad school, trying to focus on his work. “I meditated, did yoga, and went to the lab every day,” he says. His parents messaged him daily, too, begging him to leave Moscow: “Get out of there immediately,” they wrote. In late February, they themselves had left Kyiv and moved to safety in Krakow.

Vygovsky says that those early days are all “lumped together” in his memory:

When it all started, the institute’s administration called me, assuring me that there’s nothing to be afraid of, that no one would arrest me, that no one would expel me, that Skoltech is above politics. Who called? I can't remember for the life of me.

Vygovsky first came to Russia ten years ago. He studied molecular and biological physics at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (“MFTI”). After getting his degree, he applied to one of Skoltech’s graduate programs.

“I came to the Center of Life Sciences in 2018,” he says. “Not long before then, Skoltech had opened a new biology lab — and our cohort became its first ‘residents.'” He remembers those days fondly:

In a typical academic lab, the more established teammates have their own equipment and pipettes, and newbies like yourself have very little to work with. You take something and it turns out to be someone else’s; people push you around. Skoltech was the first place where I had my own workstation and my own pipettes. I could conduct experiments in any volume I wanted. Other institutes close when the bell rings — but at Skoltech, you could work till late.

Daniil’s advisor was the molecular biologist Konstantin Severinov. Vygovsky studied I-E CRISPR-Cas systems responsible for adaptive immunity in bacteria. He lived in a grad student building on campus. In March, less than two weeks from the start of the invasion, police knocked on his door.

They were writing down all the residents' names, knocking on every door, making lists. They wanted to see my phone and asked whether I lived by myself. They took my Ukrainian passport and copied all the information into a notebook. This was right after my parents had messaged me: “They’ll come for you any moment, tie you up, and execute you in public!”

Daniil gave in to the pressure. He packed up and went to Strasbourg, where his advisor Severinov helped him get a spot at the Louis Pasteur University, in a synthetic microbiology lab run by David Bikard.

At the passport control on his way to France, Vygovsky burst into tears.

On the one hand, I was glad I was leaving. On the other hand, I was really sad — I was leaving behind ten years of my adult life. In Russia, I had everything: a job, friends — and here I was, leaving and imagining that I might never see any of them again… I missed them all in advance.

Cutting-edge Russian science

At the time of its inauguration in 2011, Skoltech’s greatest champion was Russia’s then-president Dmitry Medvedev. The nominally private school was chartered with the participation of the Skolkovo School of Management, Rusnano, the Foundation for Innovations, the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, and other stakeholders backed by ample government funding. In 2019, the list of Skoltech’s proprietors was joined by Sberbank.

The school proceeded to recruit an international star faculty, many of them highly regarded for their contributions to science and technology research. The graduate-only institution was going to be Russia’s first cutting-edge school of the Western type, with a modern campus and a number of well-funded research centers. To realize this vision, Skolkovo Innovation Center was going to channel state funding to Skoltech while helping its startups with tax breaks and investor contacts. Students took part in many international collaborations, contributing to new research in areas like protein structure prediction.

The roots of this grandiose project went all the way back to the Medvedev presidency, when Medvedev — then enthralled by cutting-edge innovation — sent an entire delegation of top Russian officials to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to sit for two days in MIT workshops and seminars, absorbing arcane wisdom from the West. Igor Shuvalov, Alexey Kudrin, Elvira Nabiullina, Anatoly Chubais, Vladislav Surkov, and Arkady Dvorkovich all went. On coming back, they were all expected to help turn Skoltech into the top graduate research institution in Russia.

The campus — referred to as “our own Boston” — was built just west of Moscow. The state had committed 121.6 billion rubles to funding Skoltech over a 10-year period. The language of instruction was going to be English.

A major portion of Skoltech’s lavish funding went directly to MIT. In return, the American institution promised to help Skoltech with curriculum development, faculty training, building a forward-looking intellectual-property policy, and otherwise “absorbing the unique culture of MIT.” A three-year “collaboration agreement” between MIT and Skolkovo was signed in 2011.

Skolkovo’s academic advisory board, co-presided by Nobel laureate Roger Kornberg, twice objected to signing the agreement with MIT, calling the prospective partnership a "useless waste of money." The contract obliged Skolkovo to pay MIT $302.5 million over a three-year term. But the agreement was renewed several times. In 2022, MIT stood to receive another $400 million from Skolkovo, as confirmed by a source close to Skoltech leadership.

The school’s extravagant spending did not escape the attention of Russian journalists. As a result of media reports, the institute was audited. Then, in 2015, the Attorney General launched a criminal investigation of Skolkovo’s top management, on suspicions of “aiding and abetting embezzlement.” Among the people who had to face charges was the opposition politician and former Duma deputy for the Just Russia party Ilya Ponomarev.

"As soon as the institute opened up, it started burning through money,” said one of Meduza’s sources close to the school and its academic leadership. “Foreign faculty members were housed exclusively at the Balchug,” he notes, referring to the iconic five-star hotel with views of the Kremlin. “Besides, they could take parties of any size to any Moscow restaurant for ten days, all on the institute’s tab — and Skoltech would pay for it.”

Another source, who used to work at Skoltech, couldn't recall “anything about the restaurants” —

but until they built the Skolkovo cottages, foreigners did stay at the Balchug or Hotel Ukraina, or in luxury apartments on Arbat and Kutuzov Prospect.

From the start, Skoltech faculty salaries were several times higher than pay at Russia’s other top schools. In 2019, its president, the mathematician Alexander Kuleshov, was paid 2.9 million rubles a month, as evidenced by leaked tax documents. This would have equaled around $45,000–$46,000 monthly, or half-a-million dollars per annum. Based on information from three current Skoltech professors, faculty now make 700,000–795,000 rubles a month (that is, up to $12,720, or $152,640 annually).

Most of the faculty worked at Skoltech part-time, while also teaching at other schools, including MIT. Skoltech’s founding president, Edward Crawley, also heads the MIT graduate program in System Design and Management — and a number of other faculty members have followed similar paths.

Although Skoltech students would regularly travel to MIT, sources close to the Russian institute’s leadership feel that their American partners could have done more to satisfy the “collaboration agreement.” One of them (a former employee who only recently left Skoltech) says that “all the Americans ever did was let us use their logo on promotional booklets.” Victor Lempitsky, one of Skoltech’s first professors and the former head of its computer vision research group, has a different opinion:

MIT did help — for example, we were all “voluntarily obliged” to go to Boston — to be molded there. At MIT, I met several kinds of people who would later join this project. Some of them were just local paper-pushers for whom our institute was nothing more than another MIT partnership. But there were others who really wanted to help: they took part in the research and helped write new courses for our students.

As a result, Skoltech took ninety-seventh place among the world's “top 175 young universities” according to Nature. In Dmitry Medvedev’s words, it was “in orbit”: “It’s an institute with an excellent reputation. This is exactly what we’d hoped to achieve,” he said in April 2021.

Ten months later, Russia invaded Ukraine.

When asked whether partnering with MIT had been a success, Skoltech President Alexander Kuleshov replied to Meduza: “Yes, it has been. In the past.”

Alternative schools of thought

Victor Lempitsky taught deep learning and headed a computer vision lab at Skoltech, while also working for Yandex and Samsung. He did not believe the rumors of impending war. When it finally broke out, he found himself “watching the unfolding events in a stupor.”

Four days into the invasion, a group of Skoltech students wrote a letter to the faculty and administration, declaring their collective anti-war position and inviting their mentors to join their protest. Lempitsky and several other professors opened a Google doc and drafted, as he recalls, “some fairly banal words about being against everything that was happening, rejecting it categorically, and so forth.”

We invited everybody to sign it, but Skoltech President Alexander Kuleshov told us the consequences would be catastrophic: the institute might be closed.

(When asked about this, Kuleshov replied that he “doesn’t know” of any faculty letter, and that he didn’t influence its publication “either directly or indirectly.”)

Lempitsky felt wrong-footed by his position:

I only worked at Skoltech one day a week, and already had a ticket to Yerevan. I could have signed that letter without risking anything at all. Meanwhile, there were other signatories: professors who couldn’t leave because they had families to support, labs, and students who depended on them. So I wrote to everyone: “If you don’t want to, let’s just not do this.” And everyone kind of agreed: okay, let’s not.

In the end, Skoltech faculty didn’t put out a letter. Those of them who wanted to make a public statement signed an open letter published online by the scientific journal T-Invariant. Out of Skoltech’s entire community of 600, only 67 signed the open letter of protest against the war.

On March 14, Lempitsky flew to Yerevan, feeling uneasy:

After four years of working part-time, I no longer had a large research group at Skoltech, nor did I have any long-term obligations. Staying in Russia wasn’t an option for me, for several reasons, including my own timidity: I used to go to anti-war protests until people started getting real prison terms for it. Once this started, I realized that I wasn’t ready to protest anymore. But living in silence didn’t seem attractive to me, either.

Meanwhile, Egor Bazykin, a professor of Skoltech’s Center for Molecular and Cell Biology, not only protested, but also offered his help to colleagues arrested at the rallies. A student at the Skoltech Life Sciences center remembers:

As soon as I was released from the police station, where they took me after the March 6 protest, Bazykin messaged me with a few warm words, and offered any help that he could give me.

Skoltech’s President Alexander Kuleshov did not make any anti-war statements. Neither did he make any statements in support of the invasion. According to one of Meduza's sources:

There was this open letter from the presidents of large Russian universities who supported the “special [military] operation.” Kuleshov didn’t sign it, which is something that we pride ourselves on at Skoltech. No sane university president who cares about his institution would ever sign an open anti-war statement, and Kuleshov’s refusal is enough of a gesture in itself.

When Meduza asked Kuleshov about this decision, he replied with only two words: “No comment.”

The ‘nuclear briefcase’ and private security

A faculty member recalls how Kuleshov used to joke about his proximity to the budget: “You don’t need to worry about me stealing,” he would say, “because I’m already rich.”

Kuleshov’s candidacy for the post at Skoltech was approved by the board of directors late in 2015. A self-described “mathematician-turned-engineer,” Kuleshov was an exceptionally enterprising, and consequently wealthy, person. As one of his acquaintances put it:

He was a working applied scientist who headed the Institute for Information Transmission Problems of the Russian Academy of Sciences before joining Skoltech, so he understood communication technologies extremely well. Besides, he would personally pay for all manner of banquets for IITP academics. He was no Deripaska, of course, but he had money.

(In response to Meduza’s query on IITP, Kuleshov said only that “what happened in Vegas stays in Vegas.”)

Kuleshov began his career at the NIIAA (a Moscow-based computation think tank founded in 1956), working on control systems for strategic nuclear weapons — “including the notorious nuclear briefcase,” as he admitted in a 2014 interview. In the 1990s, he became an entrepreneur: by his own admission, he owned an IT company “in Western Europe.” In 2010, already in his IITP post, Kuleshov registered five different companies offering services in “private security” and “entrepreneurship consulting.” Two of them, Excalibur-SMS and Excalibur-2000, became profitable, making a total of 19 million rubles in 2019, when Kuleshov’s personal income was about 4.6 million rubles (or about $73,000) per month, according to public tax data.

When Kuleshov came to Skoltech, the first thing he did was cut expenses, putting an end to faculty stays in luxury apartments and five-star hotels. His next move was to partner with the Higher School of Economics: the elite Moscow university would supply Skoltech with students, who would be drawn into its orbit by Skoltech undergraduate offerings at the HSE.

Igor Krichever, a Columbia mathematics professor and former director of Skoltech Center for Advanced Studies, told Meduza (shortly before his death on December 1) that Kuleshov wanted Skoltech to offer undergraduate degrees: even though the school had been conceived as a graduate institution, he dreamed of turning it into a full-fledged university.

“I think the war will make this quite a bit more difficult,” says Alexander Braverman, who worked at the Center for Advanced Studies in the past. “On the other hand,” he adds, “Kuleshov is an unbelievably effective person, and he hasn’t yet had an idea that he couldn’t realize.” (When asked about his plans for a baccalaureate at Skoltech, Kuleshov replied: “It’ll come.”)

But the war has dealt a real blow to these plans. In early August, the U.S. State Department introduced sanctions against both Skoltech and the Skolkovo foundation. This prompted Kuleshov to publish a statement, addressing the Skoltech community: “The Western establishment,” he wrote, “is interested in maximally depleting Russia’s intellectual potential.” Despite the possibility of “significant losses,” Skoltech would “manage,” he continued. “Everything that’s happening today in the world is surreal and smacks of madhouse,” he wrote, alluding cautiously to the war. “This is why we need to keep a cold head and stay calm, more than ever before.”

Old friends, new problems

Explaining the sanctions, the U.S. State Department released a statement, which said that “for nearly a decade, Skoltech had a close relationship with Russia’s defense sector.” “Contributors to Skoltech’s endowment include numerous sanctioned Russian weapons development entities,” the statement continued.

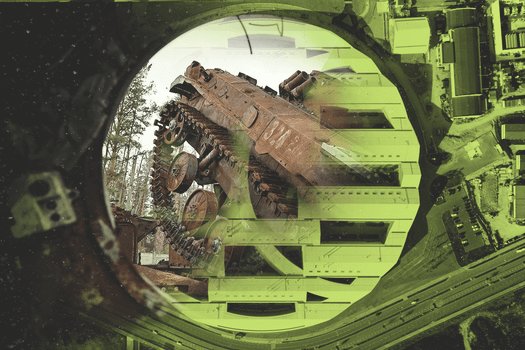

Over the course of the last decade, Skoltech has had partnerships with numerous Russian defense enterprises – including Uralvagonzavod, United Engine Corporation, and United Aircraft Corporation – which have focused on developing composite materials for tanks, engines for ships, specialized materials for aircraft wings, and innovations for defense-related helicopters.

“Defense enterprises” did, in fact, transfer funds to Skoltech — under Medvedev’s order for mandatory contributions to the school’s endowment. But faculty members disagree with the State Department’s assertions about Skoltech’s relationships with the defense industry: “We don’t have any military projects, and never had any,” said Kuleshov in an interview to Rossiyskaya Gazeta. “Everything that concerns defense and specific industry organizations,” he said, referring to the State Department allegations, “is complete nonsense.” In response to queries from Meduza, Kuleshov repeated that Skoltech “never worked with any defense enterprises.”

A member of the school’s administration who spoke to Meduza was incredulous at the mere suggestion of Skoltech’s defense contracts: “Who would give them to an international institute whose professors are Western nationals, from countries now considered ‘hostile’ to ourselves?”

Igor Krichever was certain: “Skoltech was sanctioned because it had opened up with such fanfare, not because of defense contracts.” “I was the head of its Faculty Search Committee,” he went on, “and I can say with confidence that at no time at all did I see any defense work happening there. Skoltech had no military contracts.”

Another source at the Skolkovo Foundation is equally skeptical about Skoltech’s defense ties: “If someone asked me about it point blank, I’d say that Skoltech didn’t do squat for defense. Defense contracts, deliberate research on some military problem? Definitely not.”

But Skoltech did collaborate with the defense industry, at least on paper. Its Materials Technologies Center listed several defense enterprises as partners. They were the United Aircraft Corporation (OAK), the rocket-and-space corporation Energia, Russian Helicopters, and Rosatom. In 2012, Skoltech signed an agreement to collaborate with Oboronprom and UralVagonZavod, two companies within the umbrella of the Rostec defense conglomerate. (Oboronprom was dissolved in 2018.) “Industrial concerns are flocking towards Skokovo,” said Alexey Sitnikov, Skoltech’s vice-president for communications, after the agreement was signed. (Sitnikov declined to answer questions from Meduza.)

UralVagonZavod planned to invest a billion rubles in Skoltech’s research on composite materials, but in the end their collaboration boiled down to “a single hackathon for UVZ employees,” as described by a source at Skoltech. An insider at Rostec shares similar impressions from the other side: “I don’t remember any discussions about collaborating with Skoltech,” he says. “All these agreements were a mere formality and definitely had nothing to do with tanks,” says a source close to the Skolkovo administration.

Skoltech’s agreements with Oboronprom and UralVagonZavod were signed by its American founding president, Edward Crawley. A source close to the Skolkovo leadership noted the following:

Dealing with corporations gives an institute opportunities to solve real problems — and that’s why, I think, Crawley signed all that stuff. This is done by all kinds of institutes around the world, and it doesn’t have to involve making tanks.

Alexander Kuleshov told Meduza that Crawley “had signed some quantity of nonsensical memos that were never binding.” Another faculty member recalled what went on under the school’s first president:

Crawley was in charge of the institute between 2011 and 2016. All that time, state-owned companies, including the defense industry, contributed to the endowment and signed collaboration agreements. And MIT was perfectly happy to work with Skoltech. They didn’t have any qualms about it whatsoever. MIT professor John Deutsch, the former U.S. Central Intelligence director, was on Skoltech’s advisory board to boot. And that was fine, too, and there weren’t any sanctions! Everyone was perfectly happy, and no one noticed any defense contracts. And then they suddenly woke up!

A Skolkovo insider tells Meduza that MIT “should have stood on its principles” when Russia annexed Crimea and shot down the Malaysia Airlines passenger plane — but in reality, it only took a stand much later.

Edward Crawley did not respond to Meduza’s queries.

How science became political

After the introduction of U.S. sanctions, Mikhail Lebedev — head of Skoltech Neuro, a center for neurobiology and brain rehabilitation — decided to resign from his position. Over the next month, he wrapped up his research at the institute. As a citizen of both Russia and the U.S., Lebedev was concerned about being fined by the U.S. government, but he worried about his colleagues, too:

I wasn’t fired because of some misdeed... But still, it’s been extremely awkward: I had a dozen researchers, we were all working... Incidents like this really don’t help with research.

Lebedev’s main research deals with rehabilitating survivors of stroke and spinal injuries. Skoltech Neuro was developing new treatments for them, funded by grants from the Ministry of Science and the Russian Science Foundation. Lebedev says that “post-stroke patients cannot voluntarily move their arms”:

we came up with a neural interface for sensing the patient’s intent to make a movement, and making that movement with the help of a robot holding up the patient’s arm.

Lebedev thinks that governments that implement sanctions are behaving “sub-optimally.” He believes that science doesn’t know borders, and that discriminating against scientists on the basis of nationality is stupid. “I don’t really understand why they chose to sanction Skoltech — it was originally a joint project with MIT,” he says. Lebedev continues to consult Russian colleagues on questions in his expert area: “If someone at Skoltech asks me about something — say, the neural correlates of consciousness — I’ll talk to them. Let’s not be absurd.” He also continues to teach his course on neural interfaces and neurotechnologies at Moscow State University. MSU President Victor Sadovnichy was the first to sign a collective letter by Russian academics in support of the “special military operation.” Lebedev, on the other hand, hasn't signed any open letters and prefers not to make “profound political statements”:

I could comment on something, but it might turn out to be a violation of some law. I’m an atheist, and I think that the priests are just a bunch of charlatans, but we’re not supposed to say that these days — it might even be forbidden. When Russian officials talk — and this is true of U.S. officials, too — their every other word is “god.” This superstitious ignorance gets in the way of science.

The advent of chaos

“I wouldn’t say that things suddenly got worse after the sanctions,” says Victor Lempitsky, a former Skoltech faculty member. “They were already bad on February 24.” Two days into the full-scale invasion, MIT ended its relationship with Skoltech, qualifying the war as unacceptable. Other foreign institutions also ended their partnerships. Molecular biologist Dmitry Gilyarov, who heads a research group at the John Innes Centre in Norwich, UK, describes what happened to Skoltech grad students who had been invited to work on crystals at the Durham University in England:

When they got there, the war broke out — and their bank cards stopped working, and so on. Then the Durham administration said that they wanted to end all collaborations with Russian organizations in principle, and a couple of months later the students were shown the door.

Gilyarov learned about their English misadventures on Facebook, and invited them to the John Innes Centre:

This is England, too, and I had the technical conditions for work. They came, and we made a bunch of different crystals together.

When the crystals were ready, their molecular structure had to be analyzed at the Diamond Light Source synchrotron facility. “It’s an independent British organization that we work with,” says Gilyarov:

We just send them the crystals in the mail, without even going there in person. It turned out that they wouldn’t work with Russian organizations, and had stopped all collaborations with Russia. Crystals made by Russian hands also couldn’t be submitted to the synchrotron. If a team has Russian scientists, nothing can be done.

Before leaving for Russia in early summer, the students tried to “order and buy anything they could — to bring back to Russia basic things like synthetic genes and antibodies,” Gilyarov remembers. By that time, their home institution was already feeling the shortage of reagents. Konstantin Severinov, a molecular biologist, explains:

First, the exchange rate was freaking out and prices would triple and quadruple. Then, none of the middlemen would take orders, because Western companies refused to work with Russia. Then deliveries simply stopped.

Faculty flight

Until late August 2022, Konstantin Severinov led a metagenomics lab at Skoltech. His position is now occupied by Artem Isaev. Isaev was born in Ukraine and went to school there. Later, his family moved to Nizhny Novgorod. He got a degree in biology and a Russian citizenship. For the past several years, he's been in graduate school at Skoltech: “Initially,” he says, “I saw it as a stepping-stone to going abroad”:

I thought I’d improve my English, take good courses with well-known professors, get to know the international science scene. While I studied there, I had internships at York University and the University of Toronto. I went to conferences in the U.S., Germany, and Singapore. At Skoltech, you could pursue science as part of a global community.

He took over Severinov’s lab “by sheer chance”: “I wanted to do science, not administrative things,” he says, “but now I’m forced to take responsibility for the lab and its functioning.”

Severinov had left Skoltech in August, “because the institute had been sanctioned so heavily that any American working there was liable to be prosecuted, from a $250,000 fine to five years in prison.” This picture may not be wholly accurate; the U.S. Treasury clarifies what is at stake for Americans engaging in trade with Russia on its website. Still, by early fall, Severinov and 16 other American faculty left Skoltech (as acknowledged by Alexander Kuleshov in a late November interview).

“I left, and several others did too — possibly our best researchers,” Igor Krichever told Meduza. A citizen of both Russia and the U.S., Krichever died in New York City on December 1. When speaking to Meduza not long before his death, he was exasperated:

This is completely atrocious nonsense, but, under American law, I don't think I have any right to consult a student from an “enemy” country. I think that science should be above politics, but there are plenty of idiots on both sides of the Atlantic.

In advance of more sweeping sanctions, six out of 14 lead researchers at Skoltech’s various centers left the institute. (Meduza learned about this from a slideshow shared by a Skoltech insider.) The new research center leads are solving not scientific but supply problems: “Our Bruker mass spectrometer broke recently,” says Isaev, who took over a metagenomics lab. “The manufacturer has left Russia, the engineers are all gone, parts are impossible to get, and so, a basic method of our work is completely unavailable.”

In the past, Skoltech was a place where people knew no shortage of reagents and could use anything they wanted. Before the war, Severinov’s lab had a 20-million-ruble monthly budget just for expendable materials. “This year, the budget has shrunk, but the main problem isn’t money, it’s the disruption of all the supply chains,” says Isaev.

A researcher at Skoltech’s center for artificial intelligence painted a grim picture:

We used to work with large Western companies. Each project would generate about $100,000 a year for Skoltech, on average. Bosch, Huawei, Philips, and Samsung have already stopped working with us. Contracts have been terminated, money is running out.

According to Skoltech President Alexander Kuleshov, by early November 2022, 35 different partner companies had turned away from Skoltech.

A quiet place

An African student at Skoltech says that his colleagues disappeared in troves at two different points: first in February, at the start of the war, and then in September, when mobilization began. “You come to the lab,” he muses, “and they’re gone. Yesterday, they were there, and now they’ve all vanished. And you start thinking: well, what am I doing here?” The question is all the more pointed since, after February 24, Skoltech left the Bologna system, together will the rest of Russia’s higher education. The value of its diplomas plummeted.

“Skoltech used to have students from India, Latin America, Africa, and Cuba. People would sometimes come from Europe and Canada. But who will come to our country now, with this war?” wonders a former Skoltech employee. “The institute’s standing is completely uncertain: if you get a Skoltech diploma, or defend your dissertation there, who will offer you a job in the West?”

“I used to sit in the Lebedev lab at Skoltech and barely ever look sideways,” says Alexey Gorin, a graduate student at Skoltech Neuro. “But suddenly, they announced a ‘partial mobilization,’ and on September 21 someone came for me with a draft summons. Luckily, I live in Moscow but ‘reside’ near Petersburg.” Once he heard about the unsuccessful attempt to draft him into the army, Gorin left for Kazakhstan. He only came back in mid-October to sell his car and sign a power of attorney before leaving again, this time for good.

Another scientist who also left Skoltech to go abroad describes the situation:

Everyone put on a brave face, but we’re all screwed. No one wants to smuggle in reagents behind the cheek, across the border. Projects are suspended, grants have no one to supervise them. If you email your foreign colleagues from a work account, you get no answer. Equipment cannot be serviced. F**k knows where to find infidel spare parts. If something breaks, it stays broken.

The mathematician Alexander Braverman last visited the institute over the summer. “Our Center for Advanced Study looked gloomy from the very start of the war, even before the sanctions,” he says wistfully. “There was hardly anyone in the hallways and offices.”

Igor Krichever, the center’s former head, said that what he had hoped to create at Skoltech was "a place that young people who had spent some time in the West could come back to — or maybe work in without ever leaving Russia. And to some degree, I think this has worked. We’ve gathered close to all of the available mathematician-physicists in Russia, and the better part of the diaspora, too."

By “the diaspora,” Krichever was referring to scientists who had previously worked abroad. Each year, he explained, seven new students were admitted to the Master’s program at the Center for Advanced Study, to be taught by star professors like the Fields Medal laureates Andrei Okunkov and Stanislav Smirnov. Alexander Braverman, a specialist in algebraic geometry, admits that it wasn’t easy to recruit talent for the program:

Faculty exchanged messages in search of talented students, practically catching them with bare hands. In theory, Skoltech catered to international students. These were mostly Ukrainians — some of them would defend their dissertations and stay at Skoltech as full-fledged researchers. It just so happened that Ukrainians played a key role among the most active part of the student body, and did most of the seminars.

Although students from India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan would also come to Skoltech, Ukrainian physicists were considered the best, says Igor Krichever. When the invasion began, they left.

Braverman describes the Ukrainian students’ relocation to other countries:

Since late February, I spent all my time helping our Ukrainian researchers, who needed to leave Russia immediately and find temporary work abroad. In a few months, I placed three people at the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics in Bonn, where I had some contacts and where you could travel without a visa if you had a Ukrainian passport. One very talented grad student, who had planned to defend at Skoltech, left for the Netherlands in the summer 2022, and ended up defending his thesis in Leyden. Another researcher went to the University of Geneva. All in all, about ten people left.

Braverman himself left Skoltech in late August. He wasn’t enthusiastic about it, but, as a U.S. citizen, he was concerned about the sanctions:

In theory, the U.S. Treasury can make you pay a huge fine for working in a sanctioned organization. At first, I thought this only meant that I couldn’t take a salary from Skoltech. At the moment when the sanctions were rolled out, I was officially on unpaid leave. I had no financial incentive to stay, but I wanted to preserve a formal affiliation with a center where I had always liked working. But different people persuaded me that the mere fact of my affiliation with Skoltech could lead to serious problems with the U.S. government, and I finally made the decision to leave. To be honest, I still hope it’s not forever.

Among the researchers who moved to Europe with Braverman’s help was the mathematician Evgeny Makedonsky. He was born in Melitopol, a city in southern Zaporizhzhia, and graduated from the Kyiv National University. While in high school, he took a prize at the Ukrainian Math Olympiad. His high school in Melitopol was the alma mater of at least five such winners. Makedonsky says that when he went there in the aughts, Russian was the main language used socially by students. When, after finishing the university, he lived in Kyiv, he gave talks on representation theory, also in Russian. The audience had no problem with that, he recalls. Makedonsky himself sometimes sympathized with Russia more than with Ukraine: “Not with the Russian regime,” he clarifies, “but with Russia as a country”:

Half of my relatives live there, and I didn’t really like the attempts to make Ukraine uniform, like the insistence that Ukrainian should be taught in schools in entirely Russian-speaking areas.

After February 24, Makedonsky changed his mind. “I saw all these people dying and thought it would have been better for everyone to speak Ukrainian than to have Russia bomb our cities.” One of Makedonsky’s friends recently wandered upon a mine and was killed by the blast. Another one got a concussion in combat; a third friend has been wounded in an air raid.

By late October, all of Makedonsky’s Skoltech friends had left. The last ones to go were those who were subject to the draft and didn’t want to fight. Makedonsky himself found work at the Schiller University in Jena. He thinks that, as a Ukrainian working at Skoltech, he helped the Russian regime “paint a desirable picture.” He has no plans of going back.

Article by Svetlana Reiter. Translation by Anna Razumnaya.