‘I decided I wasn’t going to cross the line’ Two years ago, anti-Lukashenko protests swept Belarus. These former law enforcement officers refused to help crush the opposition movement.

Мы рассказываем честно не только про войну. Скачайте приложение.

Story by Tatyana Oshurkevich. Abridged translation by Alex Cole.

Two years ago last week, on August 9, 2020, massive protests erupted across Belarus after election officials declared the incumbent, Alexander Lukashenko, the winner of yet another presidential race marred by repressions and vote rigging. The rallies triggered a large-scale opposition movement that the Lukashenko regime violently suppressed. Belarusian law enforcement officers forcibly dispersed street protests, arrested demonstrators, and tortured them in police stations and detention centers. Although there are no longer large-scale protests in Belarus, this crackdown on dissent continues to this day. On the anniversary of the 2020 election, the independent Belarusian news outlet Zerkalo published the stories of two former law enforcement officers who agreed to go on record about refusing to take part in Lukashenko’s repressions. The following is an abridged translation of Zerkalo’s article, published with permission.

‘Sooner or later politics will be interested in you’

Sergey Kurochkin, 44, had held various “police jobs” since the 2000s. By August 2020, he was the senior operational duty officer at a district police station in Iŭje, a town in the Grodno region of Belarus.

“Even then, everything that happened in the police embarrassed me. Over time, the complaints increased. It was disgusting for me to observe some things, to brown-nose and ‘look in the mouth’ of the bosses. I came to the conclusion that our work continued not thanks to the current conditions, but in spite of them,” says Sergey. “Plus, the situation with the elections began to aggravate everything. I understood that brutal repression, as in 2010, could be repeated, but now in more perverse forms.”

Sergey recalls that in the months leading up to the 2020 presidential election, he was still “outside of politics — as befits a police officer.” But he also recalls his bosses’ constant focus on a pro-government ideology and how they connected it to everything they did. Sergey’s main job was criminal investigations, including drugs and human trafficking cases — his work wasn’t meant to be political, but it was sometimes made so. “Do you know the old saying?” he asks. “If you’re not interested in politics, sooner or later it will be interested in you.”

Sergey’s stance changed six months before the vote. He didn’t want to be involved in forcibly dispersing protesters — and this runs counter to the duties of a police officer. “From time to time, my wife asked the question: ‘What will happen if they put you on the street with shields? What decision will you make?’ At that point I decided: I’m not going to cross the line. If anything, I’ll stick my shield in the ground and say that the police are with the people,” Sergey remembers.

According to Sergey, tensions rose within the police force as election day approached. A week before the vote, when the ballots were delivered to the election commissions, police officers were assigned to every polling station. “Even then, the leadership had begun to be concerned about ‘order’ within the system. There were public statements by [then-Interior Minister Yury] Karayev, in which it was implied that we [the police] were being given carte blanche — we just needed to follow the orders of the state, and it would protect us,” Sergey explains. “This, of course, was alarming.”

On election day, August 9, Sergey was on duty at a polling station. He had already made up his mind not to make any arrests, but he didn’t really expect anything to happen in Iŭje. By the time the polls closed, however, news of countrywide opposition protests had already begun to spread. “Even though there was no Internet, information reached us, and from the snippets of news one could understand what was happening. It was clear that throughout the country, people weren’t dispersing. They realized that their votes had been stolen. They exercised their right and decided to ask why this happened,” Sergey recalls.

In Iŭje, protesters gathered peacefully outside of the District Executive Committee and chanted “Long Live Belarus!” — the police set up a cordon, but didn’t make any arrests. According to Sergey, it was close to midnight when people began to disperse, but the police officers were ordered to continue patrolling.

Then, the police force in the nearby city of Lida called for reinforcements. Ten officers happily volunteered, but Sergey refused and remained on duty at the police station. Around two o’clock in the morning he was allowed to go home. Despite being forbidden to do so, he turned off his phone before going to bed.

Sergey had the next two days off and spent them sleeping: “I didn’t pick up the phone, I didn’t want to go to work.”

When he returned to work, he had a shift at the town’s temporary detention center. The place was unrecognizable. “Usually there were a few people detained for some petty hooliganism. And now, all the cells were jam-packed with protesters from Lida,” Sergey recalls. Tasked with examining the detainees, Sergey found that most of them had bodily injuries. Relatives and lawyers called the duty station constantly, trying to establish the whereabouts of missing persons. “I simply couldn’t believe that people could be detained so harshly,” Sergey explains. “My anxiety had peaked. In the end, I made a decision: I can’t continue like this. I’ve had enough. I can’t work in the police. On August 19, I recorded a video message to the security forces and drew up a letter of resignation.”

Sergey says he knew he would have to leave the police force sooner or later, but it was still a difficult decision to make. “I asked myself, what will happen next? How will people react? What about [my] colleagues? But in the end the situation turned out to be a bellwether, it put everything into perspective,” he recalls. “After my video message, one policeman came up to me and shook my hand, saying: ‘You’re the man!’ Others thought I was a traitor.”

Sergey realized he couldn’t make a clean break when the agents from the KGB (the national intelligence agency) started making inquiries at his place of work. Despite the fact that his bosses had promised to dismiss him “on the basis of mutual consent,” he ended up getting fired for violating the terms of his contract and was obliged to pay back money to his former employer.

Fearing the worst for himself and his family, Sergey turned to the Polish consulate for help. “On September 10, our family had already crossed the Belarusian border. As it turned out, we did everything right and just in time,” Sergey explains. “Sometime later, when the regime recovered a bit, I became a defendant in a criminal case and was added to a list of terrorists.”

Sergey says that he doesn’t regret any of his decisions — including leaving the police force in August 2020.

“Right now, the security forces are just Lukashenko’s tool. He controls all levels of law enforcement. When I think about it, I get rattled and lose my temper. I just don’t understand how this is possible. Well, it’s simply not human. It’s wrong! You can’t do this — and it still happens. And as for those who are still part of this system, many take the convenient position of an ostrich. These are cowards, people who are afraid to make a decision, to step out of their comfort zone: ‘No, I’d rather just close my eyes and do what I’m told’.”

Sergey prefers not to say much about his current situation: he doesn’t want to attract attention. “I can say the following: I live in a European country, work, and care for my family,” he explains. Leaving Belarus wasn’t easy, Sergey says. At first, he worked as a courier and an international transport driver before finding a job as a security specialist.

“Of course, my life has changed dramatically. I couldn’t have imagined that I would have to leave my comfort zone, to throw [my] things into a rental car and leave under conditions [that were] extreme for my psyche. I had to leave everything in Belarus. All the little that I had earned,” Sergey admits, sighing heavily. “But two years later, I already understand that a job in the police demonstrates the attitude of the state towards people in the civil service. There was no point in staying there. I don’t regret my decision to leave at all. If before 2020 I had known what would happen, I wouldn’t have tied my life to the internal affairs agencies of Belarus.”

‘I wouldn’t have been able to live in peace’

In the summer of 2020, 35-year-old Igor Loban was working as a major cases investigator for the Grodno regional branch of the Belarusian Investigative Committee. Prior to that August, when presidential elections were held in Belarus, he was not particularly interested in politics. He felt that Lukashenko had serious support inside the country.

“Yes, I realized that the previous elections were repeatedly rigged. But it seemed to me that Lukashenko still had his 50 percent support. Therefore, until 2020, it made no sense for me to bother with this sphere. Also, society was not so politicized. I went with the flow. But two years ago, it became apparent that the people were against the government and would vote accordingly. At that moment, my views began to change: it became clear that changes could happen.”

According to Igor, the Investigative Committee is “the most intellectual department” among Belarusian law enforcement agencies — so the majority of his colleagues were aware that the time had come for political change.

That said, Igor also knew people who were happy with the way things were. “Thanks to [working in law enforcement] they moved from the countryside to the regional center, built a condo through a soft loan, and were paid a salary above the national average,” he explains. “But 99 percent of the people in our department [were] people with higher education, lawyers. They saw changes and were excited.”

In the lead-up to the elections, many of Igor’s colleagues threw their support behind opposition candidates, including Valery Tsepkalo (who ended up fleeing the country fearing arrest) and Viktor Babariko (who was arrested and later sentenced to 14 years in prison). “The majority of my colleagues from my social circle intended to vote for Svetlana Tikhanovskaya in the elections, after she was registered as a presidential candidate,” Igor recalls. “There was some conviction that changes would happen, that the country would follow the path to democratic development. As for the Investigative Committee…of course we also had skeptics who believed that none of this was likely to work out. Unfortunately, they turned out to be correct.”

Igor remembers the day of the presidential election very well. He had just been put on duty, but he was expecting the worst. “So as not to participate in the illegal actions of the security bloc, I filled out the paperwork for vacation time,” he explains. When his shift ended, Igor’s superiors tried to send him to where the protests were taking place, but he said he was on technically vacation and went home.

During his “vacation” Igor went to the protests in downtown Grodno. But he didn’t advertise the fact that he was taking part in them at first.

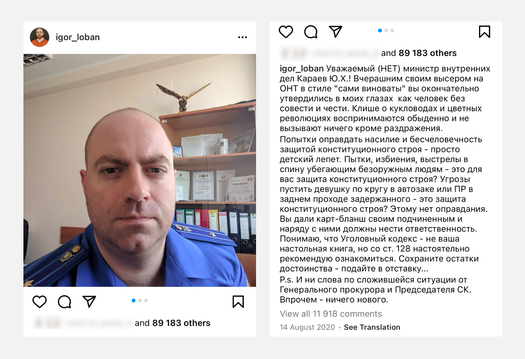

“The Internet was out in the city and when it came back and evidence of torture and excessive violence against people began to surface, I published a post on Instagram condemning the actions of the security forces and appealing to [Interior Minister] Karayev. I did not know what the reaction would be, but in the end, I saw a huge wave of support from [my] colleagues. Then I went to the central square in Grodno and gave an interview to independent media. And this is where my story began,” Igor remembers. “When the protests began to die down, it became clear that the first people the security forces would take on would be activists and their colleagues who had declared their position. That’s when I decided it was time for me to leave.”

On August 28, Igor and his family crossed the border into Poland, expecting to return home soon. “I thought I’d leave for a few months, that the opposition would develop and win, that I could return. At that moment, I didn’t even have a plan,” he recalls. Knowing that Belarus would try to send requests for his extradition through Interpol, Igor applied for international protection. As a result, his family had to live in a refugee camp for a period of time. “I will remember this phase of my life for a long time,” Igor underscores. “The conditions there were not the best. I left [Belarus] with the children, and one of them was 3.5 months old at that time.”

Igor’s family eventually moved into a family hostel and then into an apartment. His eldest child went to a Polish kindergarten and began to learn the language, while Igor found work wherever he could. He and his family are still living in Poland today — and Igor contends that things are slowly getting better. “I have enough for a normal, ordinary life. I don’t stand in lines at the secondhand store, I eat better than in Belarus,” he says. “In economic terms, I don’t live any worse.”

Igor adds that he has never regretted his decision to quit the Belarusian Investigative Committee in August 2020. “I look at law enforcement agencies now and I understand that these guys are just currying favor. Now we calmly talk about the fact that opposition was suppressed and there are no preconditions for it. And against this backdrop, the security forces feel a sense of permissiveness, their harshness stems from there,” he explains.

Igor is trying to maintain a positive outlook — despite the fact that criminal proceedings were initiated against him in Belarus and his relatives’ property was seized. The Belarusian authorities opened felony cases against Igor on charges of inciting hatred and terrorism due to his involvement in BYPOL, an organization made up of former Belarusian law enforcement officers who defected to the opposition after the 2020 election.

“I see this as the next level of pressure, but I don’t despair: if I hadn’t decided to leave then, I wouldn’t have been able to live in peace,” Igor maintains. “Nobody lives forever. Sooner or later, the evil will end […] I don’t know how my life will change, where I will be, but when changes take place in Belarus… I’d probably want to return home.”

Story by Tatyana Oshurkevich

Abridged translation by Alex Cole