‘He had a bag over his head and a broken face’ Russian mother identifies conscript son in video appearing to show Ukrainian troops shooting prisoners of war

Мы рассказываем честно не только про войну. Скачайте приложение.

In late March, a video surfaced online that appeared to show Ukrainian soldiers shooting Russian prisoners of war in the legs. Western journalists quickly sought to verify the footage and managed to pinpoint the Ukrainian town where it was filmed. In turn, Ukrainian presidential adviser Oleksiy Arestovych said that Kyiv would punish those responsible if an investigation confirmed the alleged abuse of prisoners of war. Nina, who lives in a small town in Russia’s Omsk region, first saw the footage in early April — and she immediately recognized one of the prisoners as her 20-year-old son Ivan Kudryavtsev. According to Nina, Ivan was conscripted into the Russian military in October 2021 and allegedly signed an enlistment contract after less than two months of service. But whether Ivan actually enlisted as a professional soldier remains unclear — the Russian Defense Ministry has only confirmed that he is considered missing.

The video first appeared on social media on March 27, 2022. Journalists from the BBC and France 24 later managed to pinpoint the location where it was filmed: a dairy plant in Malaya Rohan, a small town on the outskirts of Kharkiv. As reported by the French daily Libération, on March 26, Ukrainian Telegram channels had reported the capture of 30 prisoners of war in a village just a 10–minute drive from Malaya Rohan.

Ukraine’s Human Rights Commissioner Lyudmyla Denisova dismissed the footage as fake (the Ukrainian parliament fired Denisova in late May, citing her failure to organize humanitarian corridors and prisoner exchanges). In turn, Ukrainian armed forces Commander-in-Chief Valerii Zaluzhnyi claimed that Russia was filming and sharing “staged videos” in an attempt to discredit Ukrainian troops.

However, Ukrainian presidential adviser Oleksiy Arestovych later said that the video appeared to show “signs of war crimes” and promised that the incident would be investigated. Human Rights Watch also called on the Ukrainian authorities to ensure an effective investigation into the apparent abuse of prisoners of war.

The video shows several wounded men in what appear to be Russian military uniforms on the ground with their hands bound. Some of them have bags over their heads. Some of the captives also have white armbands, which Russian soldiers have used to identify themselves throughout the war (there have also been reports of civilians being told to wear white armbands in Russian-controlled areas).

A person off camera questions the prisoners, asking a wounded soldier about the location of a reconnaissance group. The prisoner begins to explain, but then abruptly falls silent. The interrogator points the barrel of a machine gun at the prisoner and pulls the bag off of his head — the captive’s eyes are open and his face is covered in blood. “He passed out,” the person off camera says.

Nina, who lives in the small town of Nazyvayevsk in Russia’s Omsk region, recognized the wounded soldier as her adopted son Ivan Kudryavtsev (Nina has a different surname, which she asked Meduza not to disclose for safety reasons). “[It was] his voice. Even before the bag was taken off, I immediately said it was him,” Nina told Meduza.

“Ivan’s voice hasn’t broken yet, it’s childlike, although he’s 20 years old,” added Ivan’s aunt Nadezhda (who also asked Meduza not to disclose her surname). “And his lips. Although he’s covered in blood, they’re plump. Even more so since they’d been injured.”

Twenty-year-old Ivan was called up for mandatory military service on October 30, 2021. On March 8, 2022, less than two weeks after Russia began its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, President Vladimir Putin assured that “conscripted soldiers are not participating and will not participate in the fighting” (in doing so, he directly contradicted Meduza’s earlier reporting about conscripts being sent to Ukraine). Russian Defense Ministry spokesman Igor Konashenkov walked back Putin’s statement a day later, admitting that there were in fact conscripts fighting in Ukraine and that some of them had been taken prisoner. At the same time, Konashenkov reported that “practically all such soldiers” (i.e., conscripts) had been “withdrawn” to Russia.

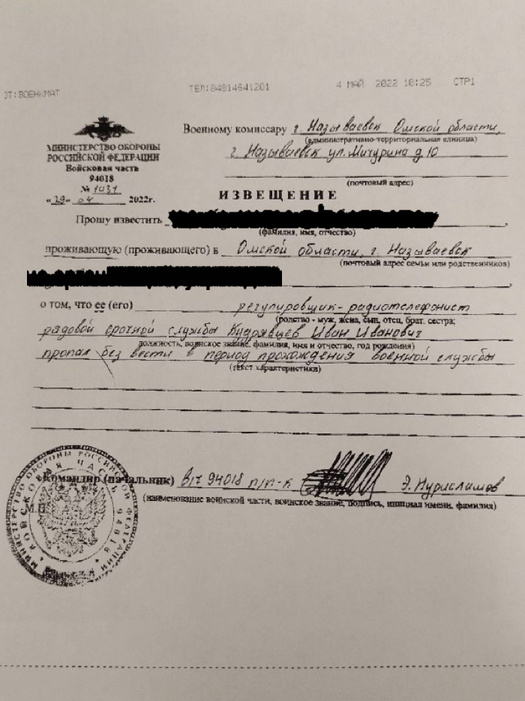

On April 29, the Russian Defense Ministry wrote up a notice addressed to Nina. The letter (reviewed by Meduza) said that “conscript Kudryavtsev, Ivan Ivanovich went missing during military service.”

‘Take us home’

Nina works as a packer at a pharmacy in Nazyvayevsk. Her hair is cut short and beginning to grey. According to her, Ivan’s biological mother (Nina’s sister-in-law) abandoned her children — two boys and a girl with cerebral palsy — after her husband left her. Ivan was seven years old at the time.

The children ended up in an orphanage. According to Nadezhda, Ivan’s brother, who is two years older, called Nina from the orphanage and asked her to “take us home.” Nina adopted her two nephews, but the family doesn’t know what happened to her niece.

Nina and her husband already had three daughters when they took in the boys. They lived in a village in the Omsk region that had neither paved roads nor a good school, so Nina moved the family to Nazyvayevsk. As a child, Ivan loved to go foraging for mushrooms and berries with his grandfather. Unlike his older brother, he didn’t do particularly well in school. He was a “C” student who loved playing soccer and watching Soviet war movies.

Ivan graduated from the Omsk Railway College in 2021. He was conscripted into the military that October. “He wanted to be a professional soldier,” Nina told Meduza. “He liked to shoot and play war. [His] older [brother] was also offered a contract [after completing mandatory service], but he refused. [My other] nephew signed a contract and is serving in Moscow. Ivan thought it would be like that. He didn’t talk about war at all.”

Ivan was sent to a military unit located near the city of Yelnya (Smolensk region). In December 2021, after less than two months of mandatory service, he told his mother that he had signed an enlistment contract “with a three-month probationary period.” His family never saw the paperwork. However, according to Russia’s law on military service, conscripts who have received secondary vocational education are entitled to enlist.

“I really don't know how he signed a contract,” Nina said, perplexed. “The swearing-in was only in November. He said that they went through accelerated training. Looks like they were preparing them [for something]. Nobody told us anything.”

On February 20, four days before Russian troops poured into Ukraine, Ivan called his biological mother and asked her for money to “buy groceries” ahead of military drills. According to Ivan, his unit “was stationed on the border with Belarus.” The next day, he messaged his older brother to say that they were being “transported” without specifying where. Ivan’s family hasn’t heard from him since.

Nina tried calling Ivan’s commander, but he didn’t answer his phone. “My oldest son only got through to him in late March. [The commander] said that Ivan was in Russia,” Nina recalled. “But then why didn’t he call himself, or at least write [to say] that everything was okay?”

On April 10, one of Ivan’s friends called Nina after seeing the video of the prisoners being shot in the legs. “He asked Nina: ‘Where’s Ivan?’,” Nadezhda recounted. “[Then] he sent a horrible video of captured boys with their legs shot and hands bound. Our [Ivan] had a bag over his head and a broken face.”

‘At least they knew their children were at war’

Ivan’s relatives called his commander right away. The commander claimed to be in the hospital. Ivan, he said, was in Russia at the time he (the commander) was injured, but he didn’t clarify when this occurred. The commander also claimed that he couldn’t watch the video properly, because his “vision had deteriorated” after he was wounded.

Nina and Nadezhda proceeded to contact other authorities — including Ivan’s military unit and the Russian Investigative Committee. “We asked questions at the military recruitment office and they shrugged,” Nadezhda said. “I remotely filed an application with the Western District Prosecutor’s Office and [was met with] silence. At first, the military unit at least answered our calls. First they said that he was on a mission and there was no cell service. Then they said Ivan was taken prisoner.”

Nina didn’t receive the official notice from the Russian Defense Ministry until May 4. In the document, Ivan is described as a “conscript” who “went missing” — it makes no mention of him signing an enlistment contract.

After trying in vain to get information about Ivan’s whereabouts from the authorities, Nina and Nadezhda turned to social media. They posted his photo online, along with an appeal for anyone with information to come forward. Shortly thereafter, Nadezhda connected with a woman from another city whose brother, a contract soldier, was also missing. As it turned out, the relatives of the other prisoners in the video had been seeking each other out all over Russia. They even had a group chat on Telegram.

“I didn’t ask how they found out about [their relatives] being taken prisoner,” Nadezhda said. “But their boys are real contract soldiers. It’s bad that they ended up in this mess, but at least their mothers knew their children were at war. Ours is the youngest, he’ll be 21 in August. We don’t know how he ended up there so green.”

According to Nadezhda, relatives have managed to identify nine soldiers in various videos filmed around Malaya Rohan. In mid-May, the relatives of one soldier wrote in the chat that his body had been returned to Russia. On June 8, another member of the group confirmed that his relative had died. The rest of the soldiers are officially considered missing.

Nadezhda said that one of the soldiers called his mother on March 21, less than a week before the video surfaced online: “He said: ‘We’re sitting in a basement, there’s no food or drink. We’re being fed by grannies and grandpas, Ukrainians.’”

Russian Defense Ministry officials have yet to clarify for Nina and Nadezhda whether or not Ivan signed an enlistment contract. Officials at the military recruitment office claimed not to know. Ivan’s military unit is no longer answering his family’s calls.

* * *

Law enforcement officials began questioning members of the relatives’ group chat in early June, according to several of its members who spoke to Meduza. Nine of the eleven people in the chat refused to talk to journalists.

Nina and Nadezhda believe that it's important to keep talking about the missing soldiers, because this might help “move the case along.” A few days before the publication of this article, a Russian Investigative Committee official contacted Nina and promised to “figure out” whether the prisoner she identified in the video is in fact Ivan, and determine his whereabouts.

“We can’t keep quiet about this,” Nadezhda underscored. “We’re ready for anything. Alive or dead, so the soul can rest. At the very least, a proper burial — so he doesn’t rot there.”

The Russian Defense Ministry, Ivan Kudryavtsev’s military unit, and the Western Military District didn’t not respond to Meduza’s questions prior to publication.

Story by Vladimir Sevrinovsky

Abridged translation by Eilish Hart