‘Putin already captured the Russians and the Belarusians. I hope he doesn’t capture the Ukrainians.’ Thousands of Belarusians moved to Ukraine after the 2020 protests. Now, many are being forced to move again.

Мы рассказываем честно не только про войну. Скачайте приложение.

After the 2020 protests in Belarus, hundreds of thousands of people fled the country. Some moved to Europe, but many chose Ukraine as their new democratic home. Now, with war on their doorstep, they’re being forced to choose between hiding, fighting against Russia, and fleeing even further into Europe. They told their stories to Meduza.

Alexandra Gerasimenya

Chairwoman of the Sports Solidarity Foundation, two-time Olympic silver medalist in swimming

I used to compete on the Belarusian national swimming team, but I stopped doing the sport more than three years ago. When the protests in Belarus began, a lot of athletes spoke out against the regime. Back then, I was criticized for supporting Lukashenko [through my athletic achievements], though now I oppose him. But I was always competing for my country’s people, not Lukashenko; I did it for the fans who worried about me.

Representing the team, I crossed paths with Lukashenko, but I was never thrilled about it. I understood that he was a terrible person, and I expressed that opinion multiple times. Because of that, there were many times when I wasn’t invited to official events. They started to exclude me from state receptions because I was “untrustworthy.”

During the protests in August 2020 and the six months that followed, I stood up for the rights of athletes who suffered at the hands of the regime. These were the athletes who were brave enough to express their position on the situation in Belarus and, as a result, lost their ability to compete, since they were fired, deprived of their pensions, or simply put in jail. Our foundation sought to ensure they could continue their careers. We organized international donation drives and competitions and negotiated with international federations to allow them to compete under neutral flags. We arranged for athletic tournaments to be moved from Belarus to other countries.

From Belarus to Ukraine

[When they cracked down on protests,] my family and I had to leave. First we went to Lithuania, then to Ukraine. I’ve lived and worked in Kyiv with my husband and my child for more than a year now.

Even though we left the country, many of our friends stayed in Belarus. The people who ended up in jail have connections to our loved ones one way or another. You worry for them just like you’d worry for your own family. I remember the death of Roman Bondarenko. I stayed up all night crying. For me, he was somebody close, not a stranger; he was someone who died for his ideals. That’s why all of the suffering that the Belarusian people are enduring to this day is on our shoulders, too. We remain there with Belarusians, if only in our thoughts. And we fight in the name of all the Belarusian people.

Six months ago, they opened a criminal case against me in Belarus. The foundation and I took it with a smile: they’d finally noticed our work, and this was their way of saying our contribution was actually quite large. It’s like what people said [during the protests]: “If you haven’t gone to jail, you’re not Belarusian.” Or, at the very least, if they haven’t filed a criminal case against you.

Like anyone who leaves their country against their will, we had a hard time at first. We had household, medical, and other issues to deal with, forms to fill out. But we got lucky — we had friends who were willing to help. They supported us and kept us from getting depressed.

I really like Ukrainians. They really are a freedom-loving people. They’re different from Russians, from Belarusians, and from every other nation. [In Belarus,] we always used to say, “Do you want it to be like Ukraine?” Yes, I do want it to be like Ukraine, because Ukraine has a lot of opportunities for business, for development. Everything’s fine in Ukraine. Sure, there are some issues with corruption and all that, but what country doesn’t have that?

War

Our foundation continued working for the last year and a half — up until the moment when Russian troops entered Ukrainian territory.

At that difficult moment, nobody, at least out of the people I know, left their homes; everybody stayed in Ukraine. Their main line of reasoning was, “This is our home. Why should we leave?”

My family and I, though, decided to leave. It’s hard to sleep well when the sirens go off several times a day because there bombs and rockets flying overhead. When we saw that Russian troops were only 30 kilometers away, we realized we had no more time to lose. So we grabbed our bags, everything we could, stuffed them in the car, and went over the border.

Now we’re in Poland. Since the war started, we’ve changed the foundation’s format. Now we’re working to help Ukraine and Ukrainian refugees. Now we’re like refugees ourselves — we keep changing countries, and we’re still trying to fight for our rights and freedoms.

We can’t return to Belarus because of the criminal charges; if I went back, they’d immediately put me in jail, or at least start the judicial process. We can’t return to Ukraine right now, either. My child, my husband, my foundation — everything’s with me, everyone’s following me, so I need to think about everyone. We weren’t prepared to leave, we just left, because we understood that life is priceless, and in the conditions we found ourselves in there, we wouldn’t have been able to work.

What’s happening right now was predictable. We at the foundation were saying a year and a half ago that Russia was actively interfering with Belarus and that it wasn’t going to lead to anything good. It’s very sad that nobody heard us. Two dictators in Europe is too many. That’s why this was all bound to happen.

Russia always interferes in other people’s business. The country is rich in land and resources, but outside of Moscow, what is life like for its people? They’re on the edge of poverty. What can that situation tell you? It’s obvious that resources are distributed unjustly. I would have asked myself why that’s happening. But a lot of people in Russia, just like in Belarus, have been sufficiently brainwashed by the constant message that we’re a great nation, we support peace, all of this is ours, we need to take what’s ours. Putin has imperial aspirations — that’s his only wish.

I see how many people are dying for nothing at all. For stupid, idiotic propaganda. This barbaric takeover of foreign takeover is happening all because of the ambition of one person.

Ales Piletsky

Former photojournalist for Tut.by, currently working for the Free Belarus Center

In the early 2010s, I was in sales. Then the crisis began, and I lost all of my investments — like sand through my fingers. My wife and I had put off having kids; we’d wanted to get on our feet first. Then when the kids appeared, the crisis hit. It hit me really hard and sent me into a depression.

Photography had always been a hobby for me. I would pick up my camera to take my mind off things. That’s how I got into journalism. Different outlets started inviting me to work for them, and in 2016, I started doing it full time.

I always thought I was an apolitical person — then I learned that if you’re not interested in politics, it’ll take interest in you.

The first time that happened was at the beginning of the pandemic in Belarus. [The authorities] were saying COVID wasn’t in our country, just like they said there was no economic crisis. And I became the first photojournalist in Belarus to do a photo report from the red zone. On the second day, someone asked if I’d heard the news. The report had gotten a huge response, and it turned out that after it was published, the head doctor at the Vitebsk Emergency Medical Hospital had been removed from his post.

The protests in Belarus

At the protests, I was an accredited journalist for Tut.by, I had documents. I didn’t express my position, I worked as professional as possible, but I was still picked up off the street. At first, they would just check the journalists’ documents and escort us to the police department. But then it turned into an intentional hunt. “If there’s no journalist, there’s no report.”

[I remember] returning home after one of the protests in the center of Vitebsk. It was still light out. A minibus pulled up behind me, and people in masks pulled me right off of the street. I yelled my last name and that I was a journalist. That was one of our techniques [during the protests], if we were being taken away — to at least make it possible to connect the dots, to make sure someone passing by would see or hear what was happening. I started screaming my last name, and they strangled me. When I came to, I was being pinned down by somebody’s knee in a bus. They took me to the police station. Without any reason, without presenting any claims, they just took me in. There were many times when law enforcement agents would order me to give up my photo equipment or to show them photos.

My only desire was to shine a line on what was happening in the streets of our city. I saved all of the photo reports on hard drives. When they began conducting searches of journalists in April 2021, it became clear that it wasn’t safe for me to work at home or to keep my materials there. At that point, I was already getting calls from Europe asking me to try to save my archive; these pictures were markers of history. I decided it was my duty, and I started hiding the hard drives in my friends’ homes.

In May 2021, I went to Minsk to do a report for Delfi about the Belarus High Technologies Park. When I finished working, there was still some time left over, and I decided to take a walk to the Tut.by office. Right then, I got a call: “Stay away from the office — they broke in.” Thirty minutes later, I got a call from my neighbors in Vitebsk saying they’d seen some people ringing my doorbell. I got in touch with some human rights workers and asked them what I should do. They just twirled their fingers around their temples and said, “Ales, you need to hop on a plane and fly away from here.”

A new life

There was no land route out of Belarus, and Belarusian airspace was supposed to close any day now. They’d intercepted the Ryanair flight at that time, and the land borders were blocked because of COVID. I decided to risk it, went home to Vitebsk, and got a ticket to Kyiv, where I flew several days later.

I stood on the edge of the abyss and just jumped into the unknown, leaving my family behind, because my financial situation didn’t allow me to take them along. In Ukraine, I didn’t have relatives, friends, or acquaintances. At first, I had nowhere to stay and nobody to talk to, but then I got in touch with the Free Belarus Center.

They accepted me into a special program, and I took a three-month course — sort of an internship. They paid 500 dollars a month, and I got to take photographs. On the second month, with the center’s help, I organized an exhibition on Kyiv’s central square: “A year of protest after the presidential election in the Republic of Belarus.” It featured my shots and photographs of my colleagues with explanatory captions. For example, what a VPN is. Back then, young people [in Ukraine] didn’t know what a VPN is, but in Belarus, even old people had learned about them by then.

In Belarus, I was afraid to bring my camera with me, and I sometimes worked in secret. I would climb into stores and shoot from behind the glass, or shoot from windows, always hiding, always afraid they would take my equipment away or break it.

In Kyiv, people laughed when I asked if I could take pictures. There’s the police, there’s the military, over there some security vehicles are going by — and you can photograph it all. I started to calm down, but it took me a long time to get used to it. To this day, whenever a minibus pulls up, my brain understands that there’s nothing to be afraid of, but my whole body starts tingling. I break out into a cold sweat, I get goosebumps, and I have to reassure myself that everything’s okay, there’s no reason to be scared.

‘Dad, why didn’t you leave?’

I didn’t believe there could be a war in Europe in the 21st century. That’s why I didn’t plan to leave Ukraine. I wanted to work in Kyiv. The Free Belarus Center organizes co-living spaces with Belarusian refugees. That’s where I lived. It’s a regular apartment where refugees settle down, and they provide a month of free rent to give you time to adapt. They made me the coordinator.

On February 24, when I heard the explosions, I called the organization's main office. They’d made a decision to change the co-living space’s direction and to create a hub for refugees and to prepare evacuation buses. My task was to gather all of the Belarusians. I set off with the bus and worked on it on the way to Poland. There was no point in staying in Kyiv — I needed to get people out. Returning to Belarus was also too dangerous.

Belarus is a base, a testing site for Russia. All of its manifestations, the penal system, the pressuring people with fines — we’re seeing it all right now on the streets of Russia.

When I was 10 years old, I had to deal with my stepdad and mom (both engineers) getting fired from work. There were empty shelves in the stores, no cigarettes, and problems with the food supply. That’s when I saw our more resourceful relatives going to Poland, selling things, earning however they could. My parents sat at home. Since they were engineers, they came up with a mechanism — a small machine that rolled cigarettes from tobacco. And they would sit there in the evenings and roll cigarettes.

At the age of 10, I imagined that I was grown, I had a family, children, and we were sitting at the table, my children about 20 years old. We lived in Belarus, and everything [the dictatorship] was still going on. And my children asked me, “Dad, couldn’t you leave? Why didn’t you leave?” And that question is constantly ringing in my head.

I’m not especially worried for myself, and it doesn’t matter that much to me: I’ve seen everything in my life. But giving my children an alternative — now that’s important to me. Taking my kids somewhere else, somewhere they’ll get an education and have some agency over their lives. And I don’t have the right to meddle in their lives beyond that — let them return to Belarus, Russia, Ukraine, wherever they want. But I want to give my kids an alternative that I didn’t have.

Anastasia Shpakovskaya

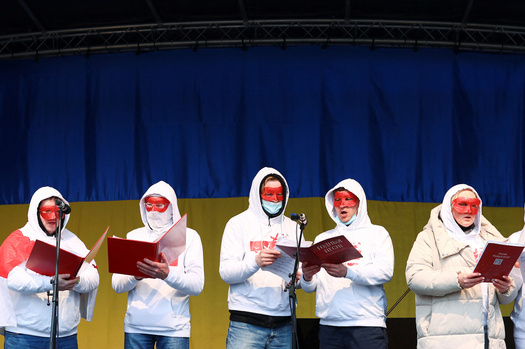

Singer, actress, member of the Belarusian band Naka

I’m not a professional politician, but all my life I’ve expressed my civic position on what’s happening in my country. And my position has always been clear and honest.

It’s hard to find the boundary between a civic position and political action when you’re constantly watching the oppression of your own people. If you’ve lived in a dictatorship for your entire conscious life, the line between politics and humanity is very thin. Naka, the band I’m the leader of, has been on the black list since 2011.

They’ve put pressure on me because I took part in the work of [former opposition candidate Viktor] Babariko’s team. When the repression in our country began, I received calls from some unpleasant male voices who wanted to know whether I felt confident about my children’s safety. Some provocative Telegram groups with the name “Judases” began leaking my personal data.

On August 24, 2020, because of the threats, my husband and I decided to take our two children and leave the country. Our kids didn’t have visas, and we needed to leave immediately to keep them from harm. That’s why I chose Ukraine.

Life in Ukraine

In the first few months in Ukraine, my head was just spinning from the freedom — it was a completely different country. Sure, there were a lot of economic difficulties; that’s natural for a country that’s been at war for eight years. But on the level of democracy and opportunities, it was a breath of fresh air after living in Belarus.

I managed to organize the first Belarusian school for children from Belarus who were forced to leave the Motherland like us. There were also musical and theater projects. Everything was settled. And then the war happened.

Listening to the Russian leader’s statements about recognizing the DNR and the LNR, we realized it was inevitable. Something would happen very soon. We left Kyiv before the missiles and the building explosions, before the nightmare began. The war caught us in Lviv.

I was looking at photographs from the streets we’d driven on just the day before. And there were explosions and missile strikes. We needed to escape as soon as possible. We packed everything quickly and got to the Polish border in a matter of hours. We were number 190 in the line to leave the country. We parked in five minutes, the line was already over the horizon, but we couldn’t imagine how long it would be. People who left Lviv just four hours after us didn’t get into Poland for two more days.

The stream of migrants is still going on today. What we see in Warsaw is a humanitarian catastrophe. We stayed with some friends in tight conditions, four people in a room. Renting a place is impossible right now. There are so many migrants, so many women with children; people are scared there will be a nuclear war.

All of our plans depend on just one person — Putin. Maybe we’ll have to look for a place to live on a different continent. The fate of half the world depends on what’s going on in this person’s head. Nobody’s expected a miracle from him for a long time, but the way he’s lying so brazenly right now, what he’s doing with the peaceful people of Ukraine, it’s beyond evil. Everyone sees how he tries to spread the “Russian world,” and what happens next in those countries. You don’t have to be a genius to see that wherever Russia goes with its “special peacekeeping operations,” what follows is blood and the destruction of all living things.

The Russian people have one more chance to go down in history as a truly great people — they can prove that the Russian people aren’t Putin. Just as we’re trying to prove that Lukashenko is not Belarus.

Alexey

Works at an IT company

Me, my wife, and our child all left Belarus in August of last year. Our child was going to school, and Lukashenko said education was his priority. They closed a lot of private schools, and in the public schools, they started emphasizing patriotism, the role of the West, the U.S. We started actively going to protests and even started carefully taking our son to them. It was wildly scary, but we wanted to show him what was happening, who was who. It was clear where the situation was headed: people were protesting, but they weren’t winning.

Anything associated with the opposition was classified as terrorism. People started going to jail for their comments on social media — they started getting real sentences. Since it’s difficult to move in the middle of the school year, we decided to go to Ukraine, and we moved to Kyiv.

I thought the only way I could oppose the regime was by taking my tax money out of Belarus. Sure, it might be small, but at least it’s something. I’ll just stop financing it. And Ukraine is culturally similar. My wife had an office here and a company that supported her; they were transferring people to Ukraine.

The KGB keeps its finger on the pulse

For the first two weeks after the move, it felt like we were at a resort. In Belarus, you always feel like you’re under surveillance, like somebody’s working on you; if you ever feel free, it’s not your achievement, it’s their failure. And here we just felt free. You’re out from under their clutches; you can freely say whatever you want in the middle of the street and you don’t have to look around to see if someone heard.

But then I got a message from the Belarusian KGB. Strangers called me by my first name: “Alexey Sergeyevich, we know you last entered Ukraine on December 18. Do you want to return, perhaps? We can help you.” The KGB keeps its finger on the pulse. I didn’t answer them. They obviously want people who left to feel like we’re still under surveillance, that we have to be careful what we say, and that we shouldn’t participate in any protests against the regime. Like, “Guys, you think you escaped us and you can be free? No, you can’t be free.”

I remember when people in Belarus first started going out to protest, the resistance was growing, there were moments of dual power. Some people didn’t obey: the government would give an order, but people’s consciences would give them a different order. There was a moment of inspiration, when part of the government didn’t support the cops. It started to work. I saw it myself, when they started calling the first responders to take down [protest] flags. They would arrive with the cops. And the emergency services commander would park the car so that the cops couldn’t see what was going on. Then they climbed up, grabbed the flag, climbed back down the ladder to the area the cops couldn’t see, and just gave the flag back to the people.

But the internal protest didn’t succeed. Lukashenko fought to the end — he was ready to either win or die. And there was no leader capable of offering the same agenda for the victory of the protest. People protested, they came out, but there was no plan to come out and to stay as long as it took. That’s probably why nothing changed.

If the Russian president hadn’t interfered and supported Lukashenko during the protests, everything would have gone differently. When the protests were first starting, there was a moment when people started resigning from the state TV networks en masse. That’s when those who were willing arrived from Russia.

Right now, Lukashenko’s economy depends completely on Putin, because if Russia hadn’t given Lukashenko loans and supported him, he would already have defaulted. It benefits the Kremlin to maintain this configuration — otherwise they’d have to deal with political instability in Belarus.

Putin has already captured the Russians and the Belarusians. I hope he doesn’t capture the Ukrainians.

Life in Ukraine

Before the war, the Ukrainian government resembled a show in some ways. There’s no doubt nationalists are present in Ukraine. A lot of people are present. You have veterans, you have gypsies. And four every situation, you’d get four different TV reports from four different perspectives. An element of a bazaar, a show, everyone blaming each other for something, everyone selling each other out. At the same time, the country keeps running somehow, the democratic institutions work, you have a lot more autonomy. People have autonomy and they use it.

Belarus doesn’t have that, and neither does Russia — they only have the power vertical. In Ukraine, elections are elections. And that’s always a show, too. Nobody can ever answer the question, “Who will be the next president of Ukraine?” before the answer is announced. Though I understand that if Zelensky stays alive, he’ll be the next president of Ukraine. That’s obvious to everyone. But before the war, there was no answer. Who Belarus’s next president will be, who Russia’s next president will be — everybody knows. That’s one of the key differences.

Ukraine is a lot freer than Belarus from an economic perspective, too. We have a park outside our house, and we see guys just setting up kiosks, making pancakes and coffee. In Belarus, we lived next to Komsomol Lake, also a park, and there was just one shish kebab place on the whole territory.

Ukraine has the breath of private initiative. There’s economic chaos, a kind of anarchy, but it’s normal in this culture. Ukrainians are used to it. There’s some noise around, not everybody agrees on everything. But that’s part of the country’s vital process, part of Ukrainian culture before the war.

War

I was skeptical about the prospect of a war starting because no rational person would have started this war. But I realized that he [Putin] is crazy. He can’t quite be a psychologically healthy person if he believes Ukraine is an “anti-Russian” project.

At the beginning of the war, we left Irpen. We thought about going closer to the western border, to Ivano-Frankivsk, but our son’s classmate’s family was staying near Zhytomyr and offered to let us stay with them. We accepted. Moving through Ukraine with a Belarusian license plate is a little bit hard right now: people are prejudiced, and it’s completely justified. You’ll just be driving, and someone will start filming you as an occupier. That’s the reality Belarusians in Ukraine are living in right now.

I broke my leg in December, and now I’m on crutches. If I hadn’t broken it, I would at least be serving in the territorial defense forces right now. I really don’t want to leave Ukraine, although my wife is afraid and wants to.

If this drags on, I’ll join the fight. I don’t want to run away. I don’t want to let the country fall into the paws of these creatures. I have no hatred towards Russians — I’m a Buddhist. Buddhism holds that you shouldn’t have anger towards anybody. I really don’t want to hate Russians. When you see pictures of Russian soldiers, they’re just 20-year-old kids with no life experience. They’ve been bullied into this. They were thrown into this meat grinder and told that if they refuse, they’ll be court-martialed and sentenced to 20 years. And they’ve only been alive for 19.

I’m still a Soviet person. I love the USSR, though there were a lot of dumb things about it. The main problem was that everybody kept quiet. That’s what killed the country. If you don’t admit your mistakes, you can’t correct them.

What Putin’s doing right now is based on some kind of great-power chauvinism. The Soviet Union was a national entity. It had its own culture, multiple cultures, and the whole culture was respected. So what Putin’s doing right now is the dark shadow of the Soviet Union. He needs to be stopped. Unfortunately, we can’t reach Putin, but we need to stop the weapons that are going for Ukraine’s throat right now.

Interview by Sasha Sivtsova

Translation by Sam Breazeale

(1) The protests in Belarus

In 2020, after the presidential election in Belarus, mass protests against President Alexander Lukashenko broke out throughout the country. For weeks, hundreds of thousands of people repeatedly went out on the streets to demonstrate. Over the course of the protests, at least seven people died, 4,691 criminal cases were initiated, and over 600 Belarusians were declared political prisoners. Lukashenko managed to stay in power.

(2) Roman Bondarenko

One of the people killed during the protests. On November 12, 2020, Bondarenko was beaten by a plainclothes officer, resulting in a traumatic brain injury. He died several hours later. Thousands of people went to the protest in his memory.

(3) The economic crises in Belarus

For five years, from 2008 to 2016, the Belarusian economy went through a series of crises. The national currency depreciated almost tenfold. At the beginning of 2009, a dollar was worth 2,650 Belarusian rubles; in 2016, it was worth 20,300.