‘Electronic voting must die’ Election expert Sergey Shpilkin explains how Russian officials thwart independent analysis

Мы говорим как есть не только про политику. Скачайте приложение.

When releasing this week’s voting results, Russia’s Central Election Commission deliberately withheld statistical information from independent analysts, encoding the data published on its website to prevent researchers from downloading it automatically. The voting figures now available through the commission are “encrypted,” meaning that any numbers copied from the website will appear as alphabetic code and randomized characters when pasted into external documents or spreadsheets. Statistician Sergey Shpilkin was one of the first analysts to draw attention to the election commission’s “encoded” numbers. A graduate of Moscow State University’s physics department and an elections analyst, Shpilkin has spent years downloading and studying data from the Central Election Commission in search of anomalies in Russia’s turnout and voting results. Many political scientists and ordinary voters turn to his post-election graphs for objective assessments of falsifications in Russia. Meduza special correspondent Lilia Yapparova spoke to Shpilkin to understand the arms race now underway between independent experts and Russia’s election officials.

Last year in July, on the final day of voting in Russia’s plebiscite on constitutional amendments, the Central Election Commission added a CAPTCHA to its main website, complicating independent researchers’ ability to download large amounts of ballot data. This weekend, says Sergey Shpilkin, analysts were prepared, and they quickly grabbed the early turnout numbers to get a “preliminary picture of what was happening.”

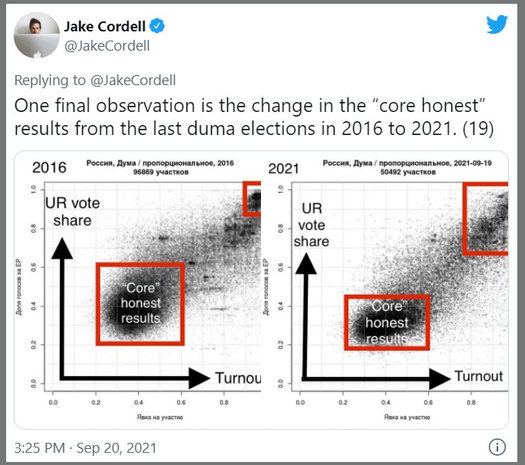

“The picture of fraud is almost the same as it was in 2016,” Shpilkin told Meduza, though he points out that “real modal turnout” was 3–5 percent higher in these elections than it was five years ago. In other words, even when downplaying the precincts with abnormally high voter participation, the most frequently recorded turnout in the 2021 parliamentary elections was higher than in 2016. Researchers also found the same suspicious asymmetry present five years ago in the peaks of turnout and votes for United Russia, though the “right tail” in the graph for this weekend’s results shifted even more to the right, meaning that Russia’s party of power performed even better this year where turnout was highest.

Based on the collected data, Shpilkin estimates that election workers falsified the lion’s share of the ballots United Russia claimed in proportional-representation voting this weekend. “It will be more than half,” he says.

Russia’s Central Election Commission introduced another online innovation this year, encoding voting results in order to thwart researchers trying to export the data for analysis. Shpilkin says these efforts by the commission are doomed. “Those who are interested in the results can draw on greater intellectual resources,” he explains, adding that the “qualified people busy with this fight” will eventually overpower the election commission. On the I.T. website Habr, for example, someone already developed a script that “repairs” the encrypted data on each page as it loads. “It’s not quite what we need for automatic collection, but it’s not so bad, either,” Shpilkin says.

In Belarus, last year, the opposition crowdsourced data collection, but Shpilkin warns that this approach is vulnerable to outside meddling. “A single ill-intentioned agent could noticeably spoil the entire results,” he told Meduza. Ideally, he says, Russia’s Central Election Commission will simply learn not to hide its numbers from the Russian public.

In the past year, however, state officials have been doing precisely the opposite. Stanisław Raczyński, a researcher at the watchdog Golos, recently noticed changes to the election commission’s bylaws that remove the language that required the agency to facilitate outsiders’ automatic data collection. In 2020, this led to CAPTCHA on the commission’s website. This year, voting results became “read-only.”

One reason officials keep trying these tricks, guesses Shpilkin, is that the decision-makers in the election commission grasp the technical limitations of data obfuscation far less than the staff who actually implement these policies. “There’s a certain gap” in understanding, he told Meduza, explaining that the people responsible for these decisions subscribe to “defensive thinking.”

Why bother at all to make it harder for independent analysts to study Russia’s election results? Shpilkin says officials are merely delaying researchers’ work so that initial reports signal the ruling party’s strength and convince the country’s elites to stay put. The preliminary data suggest that United Russia could have won a parliamentary majority (but lost its supermajority) without any falsification (thanks to plurality voting in single-mandate contests), but fear drives the election commission’s work — fear that the political elite will bandwagon wherever voters wander. “Theoretically, if these elections were normal,” says Shpilkin, “if United Russia got 35 percent and KPRF got 40 percent, we could see a power shift from United Russia to KPRF.”

In this weekend’s elections, after a handful of past “experiments,” Russia offered online ballots for the first time in multiple regions. Shpilkin does not mince words when denouncing this new technology. “Electronic voting is an absolute evil — a black box that no one controls,” he says. “It’s impossible to study a million votes piled in a single heap. You can analyze an array of numbers but we’re presented only with a few parties’ results and one turnout figure with electronic voting. There just aren’t enough details for any analysis.” Shpilkin acknowledges that researchers can examine the time dynamics in the online voting’s blockchain-based system, but little could be learned even from this approach.

“Electronic voting must die,” says Sergey Shpilkin.

Interview by Lilia Yapparova

Summary by Kevin Rothrock