‘You have no masks’ Meet the Belarusian developer working on a facial recognition algorithm for doxing riot police

Мы говорим как есть не только про политику. Скачайте приложение.

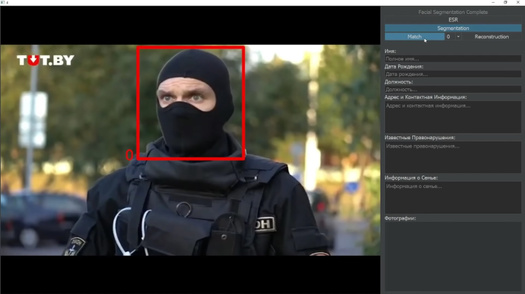

On September 24, developer Andrey Maximov uploaded a video illustrating the work of a computer program that “unmasks” Belarusian law enforcement officers. The algorithm is capable of recognizing the face of a person involved in suppressing protests, even if it’s hidden by a mask, cap, or balaclava, Maximov said in the YouTube video. But apart from the demo video, which has provoked doubts among experts, there was nothing else to confirm the existence of an actual, working algorithm. As it turns out, the program isn’t quite ready yet — in conversation with “Meduza,” Maximov said so himself.

Everyone will know your face

“It seems to me that you don’t fully understand the seriousness of your situation. You have no masks, you’re aren’t living in that era. All of your faces and all of your photos will be returned in a video of your illegal activities. No matter how many socks you wrap around your head,” Andrey Maximov said in his address to Belarusian law enforcement officers.

The developer’s video statement has garnered more than one million views on YouTube so far. But it doesn’t give any backstory about the program’s development or share details about the technology used for image recognition. The demonstration of the algorithm begins with an attempt to identify an officer from the Minsk riot police (OMON): the man, whose face is completely hidden by a balaclava, was filmed while trying to arrest a minor; the protesters around the law enforcement officer urge him to release the teenager, at which point he takes out a grenade and grabs the pin as a warning.

The video then shows the algorithm’s interface: it highlights the riot police officer’s face and runs it through a database of photographs of law enforcement officers (Maximov didn’t answer Meduza’s question about the source of this database). In addition to his name and date of birth, the program pulls up the identified officer’s address, as well as a record of his misconduct (“beat civilians on August 9–10 in Minsk”) and information about his family, including a photo taken with his son.

“In a few short years, your child will see these exact photographs in the pages of textbooks on the modern history of Belarus — and... he will ask you, with great contempt, the most difficult question of your life: ‘Papa, why didn’t you think for yourself?’” Maximov continues. “To everyone who continues to terrorize peaceful people, I promise: every person that you meet up until the end of your life will know your face.”

All total, eight people are identified in the video, but Maximov promises to “unmask” all security officers who continue to take part in suppressing opposition protests. “Your bosses and ideologues constantly tell you that your people [narod] need beating because they’re all being used for someone else’s ends,” the developer says. “Just [take] one sick day, go to a city where no one knows you, walk with Belarusians, find out why they came out, who ‘paid’ them. See for yourself what you’re beating them for.”

As it turns out, Andrey Maximov is a Belarusian game developer, who lives in California. He started his career as a 3D-animator for the Belarusian video game company Wargaming and then moved to Los Angeles and got a job at the video game company Naughty Dog, where he was quickly promoted to art director. Maximov has never worked with facial recognition technology before; his latest project is Promethean AI — an artificial intelligence that artists can use to create 3D-content for video games.

In conversation with Meduza, Maximov explains that he’s working on the facial recognition system as part of an informal group of IT specialists, who are mostly Belarusians who emigrated to the United States. “Plus a few foreigners [who] are helping,” he says. “[During] the first few weeks, when this whole nightmare started [in Belarus], I just collected money and sent it there to support people, but it soon became clear that something more needed to be done — and I got the idea of doing this kind of digital activism.”

Doxing as an instrument of influence

The first report about Maximov’s program appeared on the Belarusian opposition Telegram channel Nexta, which is also known for doxing Belarusian law enforcement officers.

On September 11, Nexta reported that Belarusian “cyber partisans” had hacked into the Belarusian Interior Ministry’s employee database and handed over the personal data of tens of thousands of “individuals from the occupiers’ structures” to the Telegram channel. Nexta promised to release the data unless the security forces stopped “carrying out criminal orders.”

Following the arrests at the women’s march on September 19, Nexta followed through on this threat: the channel published the personal data of more than a thousand law enforcement officers. “If the arrests continue, we will continue to publish this data en masse,” Nexta’s administrators warned. The channel also urged its subscribers to help with the doxing, asking them to share the personal information (“addresses, telephone numbers, license plate numbers, habits, lovers”) of law enforcement officers via a Telegram bot. “No one will remain anonymous, even under a balaclava,” they said.

The list (which has since been blocked for violating Google’s privacy policy) contained the full names of police officers, as well as their ranks and the departments of the Interior Ministry they work in. The day after their personal data was leaked, 200 people named in the database said they were prepared to quit their jobs — this was reported by Yaroslav Likhachevsky, the founder of the solidarity fund BySol, which offers financial and legal support to retired law enforcement officials. “De-anonymizing security officers is a very powerful tool for influencing them,” Likhachevsky explained.

A similar doxing channel joined Telegram back in August. Named “Punishers of Belarus — names, addresses, relatives,” it publishes pictures, phone numbers, and links to the social media pages of Belarusian law enforcement officers involved in suppressing opposition protests. The channel’s administrators don’t explain where they get their data; one post claims that they’re being sent information about riot police officers by “their very own relatives”

All of the personal information on Belarus’s law enforcement officers is being gathered in a unified database on the website narushitel.org. “People in the security structures, who, before this, thought they could commit lawlessness with impunity, have begun to fear that they might be recognized on the street, that their relatives will find out [that] they’re committing atrocities,” writes the site’s creator, who remains anonymous.

Since the start of the doxing campaigns, more than a thousand people have declared their readiness to leave law enforcement, BySol founder Yaroslav Likachevsky said.

Strange mistakes

One of the law enforcement officers identified in Andrey Maximov’s video was a large man wearing a red polo shirt, black bulletproof vest, a balaclava, and a baseball cap — a man fitting this description has been seen suppressing protests in Minsk repeatedly. In particular, there are several videos that show what he was doing on the evening of September 6, 2020. At that point in the day, law enforcement officers had started chasing people as they left a Sunday opposition march; when protesters tried hiding inside a nearby coffee shop called O’Petit, they dragged them out into the street. The man in red started beating detainees with a truncheon right in the middle of the crowd, as protesters chanted “Shame!”

In the another video, the same man can be seen chasing people fleeing along Victors’ Avenue. One of them trips and falls onto the grass — he’s surrounded immediately by unidentified individuals in plainclothes. The man in the red shirt makes his first blow with the truncheon, and the protester’s body begins to spasm. Nevertheless, the officer hits him two more times and then walks away, leaving the protester lying on the ground.

Initially, Maximov’s algorithm identified the man in the red shirt as Vitaly Kutsepalov (Kutsepalov didn’t answer Meduza’s phone calls). Later, the description of Maximov’s YouTube video was updated with a correction: “Update: Guys, information has appeared that Kutsepalov V. V., although similar, may not be him. We’re verifying now.”

Meduza found out that the “algorithm” did indeed make a mistake. “The employee in the red t-shirt and balaclava is a Valery Vysotsky, a senior security officer in the Major Crimes Unit of GUBOPiK’s Third Department,” a source close to one of Belarus’s law enforcement agencies told Meduza (Vysotsky hung up without listening to Meduza’s questions).

Belarus’s Interior Ministry later confirmed that those involved in arresting protesters near the O’Petit cafe were actually law enforcement officers — including officers from the ministry’s Main Directorate for Combating Organized Crime and Corruption (GUBOPiK). Vysotsky works for this particular branch — unlike Vitaly Kutsepalov, who no longer works for the Interior Ministry. In addition, Meduza’s source close to one of Belarus’s law enforcement agencies confirmed that Vysotsky was involved in cracking down on dissent even before the presidential election took place.

Another Telegram channel, “Punishers of Belarus Archive,” also misidentified the man in the videos as Vitaly Kutsepalov. And this isn’t the only overlap between Maximov’s video and the information posted on this channel: seven of the eight law enforcement officers identified in the YouTube demonstration had previously been exposed by Punishers of Belarus Archive. In mid-September, the channel shared the birthdates, full names, and photographs of Evgeny Savchin, Timur Grishko, Nikolai Baranovsky, Vladimir Romanyuk, Evgeny Solodky, and Dmitry Zhmuro — in other words, these officers had been identified at least a week before Maximov released the video of his facial recognition system.

In conversation with Meduza, Maximov admitted that some of the examples of de-anonymization featured in the demonstration were not a result of the program’s work; they simply borrowed information from the Punishers of Belarus Archive. The algorithm isn’t ready yet, Maximov explains, and he still doesn’t know how long it will take to refine it. “We weren’t going to show our project so quickly but because of [Alexander Lukashenko’s] sudden inauguration and the escalation of the level we were faced with a difficult choice — and it was made in order to quickly demonstrate what we have. We wanted to keep a file on law enforcement officers — to make them understand that all the technology needed to identify them [already] exist and that with time their complete identification is inevitable,” he says.

‘Real algorithms don’t work like that’

According to two of Meduza’s sources working in Russia’s recognition technology field, the problem of identifying a face covered by a mask or even a balaclava is solvable, but Maximov’s video doesn’t provide any evidence of an algorithm, not even one that’s in the development stage.

Facial recognition technologies use neural network algorithms to identify faces — artificial intelligence trained on a huge number of photographs. Not long ago, the United States’s National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) showed that the medical masks people are wearing in public during the COVID-19 pandemic are causing some recognition algorithms to fail 50 percent more often. However, facial recognition technology providers have also been learning how to cope with this during this period: in April, reports emerged that the Moscow authorities had purchased technologies from the Russian company NtechLab that are able to “identify” faces covered by scarves, complex headgear, and even motorcycle helmets.

“In connection with COVID-19, all producers quickly started working on recognizing faces hidden by masks,” Ivan Shapshal, the deputy director of the Russian biometric technology company Papillon Systems, told Meduza. “And now all advanced developers have a reliability level of 90 percent: that is, even behind a mask the algorithm finds the right face in a database of a million people with about 90 percent accuracy. The most important thing is that a small portion of the nose and eyes are visible — and the fact that [Belarusian] police officers have the upper part of the forehead hidden doesn’t have a big impact.”

As such, it’s possible that an algorithm could carry out the task outlined in Maximov’s video, Shapshal says. But the demo video itself, which is so far the only evidence of the algorithm’s existence, bears more resemblance to a “montage based on feature films” than an actual illustration of how a program works. “Real algorithms don’t work like that, as shown in this video. For example, [in Maximov’s demo] there are photos on the right that the algorithm allegedly ‘goes through’ [before identification]. This is totally unrealistic: now, an algorithm for searching a database works at such a tremendous speed that the task of displaying some intermediate results on the screen would consume all its power — the system would stop searching and only [show] the illustrations flickering on the screen,” Shapshal explains.

The Belarusian Telegram channel “Cyber Partisans,” which is also involved in doxing and is working on its own open-source solution for identifying law enforcement officers, called Maximov’s project a “fake.” “We aren’t ruling out the existence of a face recognition system but it couldn’t work under the conditions shown in the video,” the channel’s administrators said.

Psychological pressure

Maximov’s video also gives an example of facial recognition that modern technologies simply aren’t capable of — around the two minute mark, a police officers is identified despite the fact that only his ear and part of cheek are visible. “[His] mask covers his face up to the middle of his eyes, and there’s a huge brim up above, that is, the brim [of his cap] overlaps with the mask. You can’t see anything at all but the system identified [him] once again. This is in the realm of fantasy,” Shapshal told Meduza.

Andrey Maximov admits that he deliberately included an example of unrealistic technology in the video, in order to “exert psychological pressure on the security forces.” “The main goal of this video is to communicate with officials in the security structures, whose technological knowledge is relatively limited,” Maximov told Meduza. “If we need to add some things that show the security forces that there are many of their faces and names in our database, then we will add it solely for this purpose.”

“It looks like a fake: a very small percentage of the face is visible in the majority [of the photos],” said Meduza’s source from Russia’s recognition technology field, who asked not to be named. “And plus [for identification] you need an entire database [of photographs] of these very same riot police officers [from Minsk] — where did he get it from?”

A lack of data is really the biggest problem the project is facing, Maximov tells Meduza. In total, the developers managed to collect around a thousand photos believed to be of law enforcement officers from the media and social networks (usually neural networks are trained on a much larger number of images). Maximov also admits that the algorithm hasn’t been trained on pictures of people in masks. “There’s no large dataset of people with and without masks as of yet — we’re still collecting this data. Belarus’s Interior Ministry, unfortunately, doesn’t have a Facebook page with three photographs of each employee [taken] from different sides,” he complains.

Until the facial recognition program is ready, Maximov is focusing on putting together simple visualizations of the officers that activists have already identified. “We will begin to return the faces of the people who commit crimes to the photographs [of] their crimes,” Maxim tells Meduza. “Providing people with high-quality visual information is also important. So that there’s no disconnecting the two images, otherwise it [looks like] some unknown people in masks are beating people and pulling women’s hair — and in the other pictures the same guy is spinning in a field of dandelions with his dog.”

Story by Liliya Yapparova

Summary by Eilish Hart

(1) What’s that?

Doxing (sometimes spelled doxxing) is the practice of researching and publishing private or identifying information about a particular individual or group of people on the Internet.

(2) GUBOPiK

This is the acronym for the Belarusian Interior Ministry’s Main Directorate for Combating Organized Crime and Corruption.