Happy days for managed democracy Sources say the Kremlin welcomes recent election results, and Russia’s ruling political party lives to fight another day

Мы говорим как есть не только про политику. Скачайте приложение.

The Kremlin’s is pleased with last Sunday’s gubernatorial election results. Here’s what was done to prevent any runoffs.

Multiple sources close to Russia’s presidential administration told Meduza that the Kremlin is happy with pro-government candidates’ performance in the September 8, 2019, elections. Officials are especially pleased in the State Council’s Department of Affairs, which is managed by Alexander Kharichev, a close associate of Sergey Kiriyenko, President Putin’s deputy chief of staff and “domestic policy curator.” Responsible for overseeing Russia’s gubernatorial races, Kharichev’s office had a clear task: don’t allow any second-round votes. The Kremlin was eager to avoid a repeat of 2018, when the Putin administration’s candidates couldn’t win first-round elections and lost runoffs in four gubernatorial contests — including elections in the strategically important Primorsky and Khabarovsk regions.

As recently as this spring, sociologists told the newspaper Vedomosti that long-time incumbents in Vologda, Volgograd, and Stavropol could expect second-round elections, and there might be problems for the Kremlin’s candidates in Altai and Sakhalin, where locals had expressed hostility to the “outsiders” appointed by Vladimir Putin, acting governors Oleg Khorokhordin and Valery Limarenko. Until the last minute, even St. Petersburg’s gubernatorial race seemed to be in question, after a series of gaffes by acting Governor Alexander Beglov and his campaign staff.

“Mission accomplished. Everything worked out. The governors’ races are being questioned least of all, nobody disputes the results, and no one is protesting,” a source in the Kremlin told Meduza.

Another source close to the presidential administration told Meduza that Kremlin officials worked hard to prevent any runoff elections. “First, even before the elections, they didn’t let in anyone who could have accomplished anything or who risked running an active campaign. They were fine registering a high-profile [but harmless] outsider, like State Duma deputy Alexey Kornienko in Sakhalin. They were fine just not letting in anyone from the parliamentary political parties, like in Zabaikal [where acting Governor Alexander Osipov won 90 percent of the votes]. The main thing was so the competitors were such that voters wouldn’t consider supporting them even in protest,” says Meduza’s source.

The source says one example of these deliberately feeble rivals was the Communist Party’s candidate in Stavropol, General Viktor Sobolev, who declared in an interview: “I don’t see a big difference between the Krasnodar and Stavropol regions. In all respects, Stavropol is just as rich in land, mineral resources, and people.”

Kremlin officials didn’t limit themselves to the careful selection of challengers, however. According to another source, the presidential administration issued instructions to regional authorities that allowed officials to raise voter-turnout figures by as much as 25 percent. “There were different methods. One of the main directives allowed at-home voting [for convalescents and the elderly] to reach 10 percent, though these voters typically make up just two percent of the electorate. In other cases, they played ‘basketball,’ dumping not one but several ballots at once into the scanners,” says a source in Russia’s political consultant industry. Meduza checked the election results, and verified that at-home voting did in fact comprise about 10 percent of all ballots cast in 10 of the 16 gubernatorial races on September 8. The highest percentage of at-home voting — 14.6 percent — was recorded in Kursk, where acting Governor Roman Starovoit won 81 percent of all votes.

Meduza’s source says these measures were taken to neutralize the effect of potential “protest voting,” which worried the Kremlin. “That’s why you see pro-government candidates getting these enormous percentages, almost at Putin’s levels, or even more. In some places, there are also spikes in voter turnout that are strange for these elections. These figures were supposed to be plausible, given protest voting, but the protest voter didn’t turn out, so we see these numbers!” says Meduza’s source.

Another political strategist familiar with Russia’s gubernatorial campaigns recalls instructions published online by the “St. Petersburg Observers” movement, which apparently explained how election commission members could take ballots cast for one candidate and assign them to another candidate. Meduza’s source says, “This method was applied across Russia.” Another strategist with ties to the Kremlin, however, insists that “re-sorting” was only used as a last resort: “This technique is dangerous, and it’s used when nothing else works. If observers notice one candidate’s ballots in another candidate’s pile, they can demand a recount.” At the same time, another political consultant who worked in one of the September 8 gubernatorial contests denies receiving any such instructions, and insists that “re-sorting” more than 15 percent of an election’s votes would inevitably lead to a public scandal.

The Kremlin planned to reform State Duma elections, but officials might abandon this initiative because of Alexey Navalny’s “Smart Vote” system

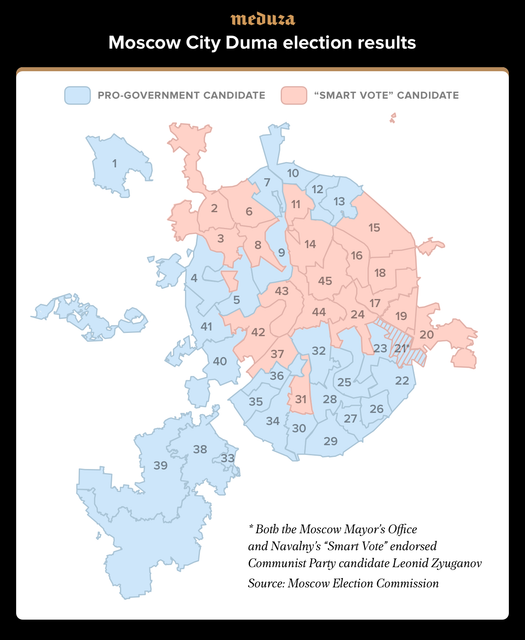

Kremlin officials planned to redesign the way Russia’s parliament is elected, ahead of the 2021 State Duma elections. Currently, half of its seats are awarded according to party lists, and the other half go to the winners of “single-mandate” races. The Putin administration allegedly wanted to expand this latter category to 75 percent of the State Duma, in response to United Russia’s suffering political brand, and politicians’ need to disassociate from the party. (In single-mandate elections, these same party members could run as independents.) In 2019, the share of local parliament seats awarded by party list fell in Tula, Khabarovsk, and Mari El. Single-mandate contests determined the entirety of the City Duma in Moscow, where United Russia didn’t nominate a single candidate (though it effectively won a 25-seat majority).

“By the end of the spring session, members of United Russia’s State Duma faction were ready for the change, saying that the key decision had been made in the Kremlin. The only resistance was in the Communist Party and LDPR, who have few strong local candidates, and hoped to solve this problem,” a source in the State Duma told Meduza.

After victories by Smart Vote candidates in Moscow and United Russia’s defeat in every Khabarovsk precinct, however, a new system that expands the share of single-mandate seats in the State Duma suddenly looks less than ideal for the Kremlin, and Russia’s 2021 parliamentary elections will likely proceed according to the existing rules.

United Russia’s fate is decided, apparently: the country’s ruling political party has managed to stay afloat

During Russia’s 2019 local election campaigns, Kremlin officials debated what role United Russia should play in the 2021 State Duma elections: would it remain the “ruling political party,” or might the president pivot to relying on the loyal “independents” who win in single-mandate races? Before September 8’s election results, the need to back away from United Russia seemed paramount, given the party’s falling ratings, ever since the government raised the retirement ages. (In August, just 28 percent of Russians said they planned to vote for United Russia candidates in local parliamentary elections — a new low.)

“United Russia whacked everybody in these elections,” said Andrey Turchak, the party’s General Council secretary. Technically, the party lost ground, compared to its performance in local elections five years ago, but one party member encouraged Meduza to consider a different reference point: “Back then [in 2014], there was the annexation of Crimea, a patriotic upsurge, and unconditional support for the authorities. These days, there’s pension reform, the standard of living is falling, and the government’s rating is falling, too, and in these conditions we managed to win majorities everywhere except Khabarovsk. It’s a huge success,” the source says.

United Russia’s performance in Khabarovsk — where the party won just 13 percent of the vote — was admittedly disastrous. But in September 8’s other races, United Russia fared far better. After Khabarovsk, its worst results were in Altai, where it won 34 percent of the vote. The Kremlin also recognizes that last Sunday’s legislative election results were a success. (Kremlin Internal Policy Department head Andrey Yarin managed Russia’s parliamentary elections, with the exception of the race in Khabarovsk, which Alexander Kharichev oversaw.) “The culprit has already been identified in Khabarovsk: it’s that damned [oppositionist Governor Sergey] Furgal,” says Meduza’s source in United Russia. “The other numbers are perfectly acceptable.”

Meduza’s United Russia source says he’s confident that the party will retain its leading status, though he acknowledges that the Kremlin has yet to make a definitive decision on the matter, and still needs to “debrief,” following the September 8 elections. A source close to the presidential administration confirmed to Meduza that no one on Putin’s team is particularly bothered by Sunday’s results. “There are no protests, Navalny’s ‘Smart Vote’ was a success, and United Russia is sitting pretty. There’s peace and quiet. But it’s important not to transpose this situation onto the State Duma elections, and not to strategize based on these results. Political parties will go head to head, there will be election observers, and there will be public interest,” says Meduza’s source.

Meanwhile, United Russia leader and Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev has already openly criticized the idea of party members running as independents in single-mandate races: “Perhaps we don’t need to use a model like this, given that it is unlikely to add anything new for us, but in many cases it’s sure to subtract something. I’m not saying this as a final decision, although the party’s congress will take place very soon, and we’ll probably once again discuss the lessons of these campaigns. I’m just asking that we think it over.”

In Moscow, meanwhile, 20 of the City Duma’s 45 seats went to “systemic opposition” candidates endorsed by Alexey Navalny’s Smart Vote system. Deputy Mayor Natalia Sergunina and her subordinate, Moscow Trade and Services head Alexey Nemeryuk, are being blamed for these results, but multiple sources told Meduza that Sergunina and Nemeryuk will retain their positions, for the time being. “It’s not customary in this system to punish anyone immediately. People are punished for mistakes, but the system doesn’t make mistakes. In six months, they’ll be ‘reassigned,’ and that will be that,” a source told Meduza.

Story by Andrey Pertsev

Translation by Kevin Rothrock