‘The art of rejection’ A new report reveals the hidden mechanisms authorities use to restrict protests in Russia

Мы говорим как есть не только про политику. Скачайте приложение.

Article 31 of the Russian Constitution states that citizens of the Russian Federation “shall have the right to assemble peacefully.” However, when protests are not approved by local authorities, those who join them can face arrest, professional consequences, and even criminal charges. The anti-corruption protests that swept Russia on March 26 and June 12, 2017, as well as the Voters’ Boycott marches of January 28, 2018, largely fell into this category of “unsanctioned” demonstrations, and hundreds of people were detained by police during each event. According to the media project OVD-Info, which reports on and combats political persecution in Russia, the process by which local governments approve or reject public gatherings remained until very recently an almost total secret—one that allowed authorities to maintain control over “how a public event proceeds, how the media covers different gatherings, and sometimes even the fates of those who participate in protests.” Natalya Smirnova and Denis Shedov of OVD-Info recently released a 75-page investigative report in Russian detailing the inconsistent norms and frequent pitfalls that await protest organizers at every stage of that process. We at Meduza read the report so you don’t have to.

If you had taken a stroll through central Moscow in mid-December of last year, you might have spotted a lone figure holding a sign outside the executive offices of Russia’s presidential administration. That figure would soon have been replaced by other figures holding similar signs, all protesting in support of the imprisoned Ukrainian filmmaker Oleg Sentsov. The protesters in this “individual picket,” many of them celebrities, chose this strange form of assembly for legal reasons: Russian law does not allow for spontaneous protests that have more than one participant.

In principle, OVD-Info argues, the purpose of this legal framework seems benign. Once notified about a planned event, local authorities are charged with protecting the rights of Russian citizens by providing security and by ensuring that the event conforms to constitutional and other legal standards. In practice, however, the Russian legal system requires both advance notice of public gatherings and the approval of local authorities. In their report, entitled “The Art of Rejection,” Smirnova and Shedov use research materials collected over several years to detail how that power to approve protests or leave them “unsanctioned” has become “an instrument of censorship” without explicitly prohibiting political opposition.

In 2018, between 8.5 percent and 23 percent of all proposed public events were rejected in every Russian city, with nationwide political demonstrations like those of January 28 facing the highest rejection rate. Smirnova and Shedov’s report centers on two main frameworks that can make these rejections into repressions of civil rights. On one hand, there is a system of laws and legal norms that regulates the approval process, but those norms can be restrictive, ambiguous, or self-contradictory. On the other hand, officials can act in ways that do not conform to any norms and are technically illegal. In either case, there are no precise rules that organizers of a demonstration can follow to ensure that their gathering will be deemed legal. There are only various tools local government actors can use to control the approval process.

Below is a summary of just a few of those tools. The full OVD-Info report provides numerous sources ranging from interviews and social media posts to court documents and government statistics. For the sake of concision, this synopsis references only a fraction of the incidents and complications they describe.

Just to request approval for protests, organizers must meet specific but hidden demands

Both local and national regulations govern whether any given protest can be officially sanctioned. Organizers can only initiate that review process by notifying local authorities of their plans via a formal request. These requests must be submitted within a specific timeframe that usually lasts only a few days.

Federal law requires that requests include nine apparently brief pieces of information. These include the name and contact information of an organizer, the aim of the event as well as its time and place, the expected number of participants, and the organizer’s plans for providing medical or security support if needed. However, any confusion concerning any of those nine points can cause the protest to be labeled unsanctioned, leaving its participants vulnerable to arrest.

That confusion often arises because local governments’ expectations for requests do not become clear until after the request is made. In 2016, journalists working for the Ekaterinburg-based news outlet 66.ru tested their local government’s approval system by submitting formal requests for 18 different pickets. Not one of the requests was approved when they were first reviewed, but not because of the nature of the proposed events. Instead, among other complaints, the journalists were told that the set of forms they had used to prepare their requests were incorrect although those same forms were published online as official examples for event organizers.

A group of actual protest organizers in Oryol encountered a yet another obstacle in their request to join nationwide demonstrations on March 26, 2017. The group had proposed six pickets but failed to indicate whether they intended to use audio equipment. A “picket,” it turns out, differs from a “meeting” in part because it cannot involve such equipment, according to Russian federal law. “Demonstrations” and “processions,” on the other hand, differ because the former involves “visible agitation” while the latter does not.

While these requirements might appear to be merely bureaucratic obstacles, they can prevent a demonstration from being sanctioned before its content is even considered. For example, when organizers in Izhevsk were told the planned route for their march was “inadequately detailed,” they took the time to present authorities with a new plan. By then, however, another event had miraculously been planned for the same date and the same place. Because federal law does not specify exactly how detailed proposed protest routes must be, organizers can bend over backward to preempt local officials: a location proposal for the March 26 protest in Oryol began with “the solar system, planet Earth.”

The time pressure for filing requests can be insurmountable

Russian law provides a strict timeline for the organizers of public assemblies to notify local officials of their plans. For most forms of protest, requests are accepted between ten and fifteen days before the day of the event, leaving just a few days for negotiations. Approval for pickets may be requested until three days before the protest.

These guidelines may seem clear, but they also contain important ambiguities. To some local governments, “days” include weekends; for others, they are limited to business days. Whether or not the day a request is submitted and the day of the event itself should be included in the fifteen-day count is often unclear, and the answer occasionally also depends on whether those days fall on weekends. As a result, organizers who plan to submit a request on the first possible day to allow for more time to negotiate with authorities are often told that they gave notice too early, leaving them fewer days to try again.

Even organizers who submit their requests on time can run afoul of the filing window. In at least one case, local officials notified organizers about an event that conflicted with their requested protest, allowed them to ask for a slightly different scheduled time, and only then notified them about a different conflict that made the second proposal unacceptable as well. By the time of that second notification, the legal filing period had passed.

Numerous locations are off-limits to protesters

Federal law in Russia lists a number of places that demonstrators cannot approach. In 2012, a new law enabled regional administrations to add their own restrictions, and since then, the areas available to protest organizers have rapidly become more restricted. For example, a central square in the city of Kostroma was marked off-limits because, in the words of one official, “it is in the center of the city, and people go there to admire the beauty of its architecture.”

In addition to prohibiting organizers from planning protests near specific landmarks, regional governments can ban certain types of places from being used for protests. Over half of Russia’s 85 regional subunits prohibit public demonstrations in the proximity of educational institutions, medical organizations, railroad stations, government buildings, airports, and religious institutions, and these account for just a fraction of the kinds of places protestors must not approach if they hope to avoid arrest. Both these prohibited places and the distance protestors must keep from them may not be publicly known until after organizers submit a request.

However, the most frequent reason officials cite when turning down requests is that the location of the planned protest will already be occupied. In most cases, there is no way for organizers to determine ahead of time whether that will be the case. In Volgograd, organizers who requested approval for a March 26 protest were told that, unbeknownst to them, a massive street cleaning sweep had been planned from March 18 through April 30 throughout the city’s entire territory. These surprise sanitary efforts functionally enabled local authorities to ban all protests in the city for more than a month. Sporting events, such as the 2018 FIFA World Cup, often have a similar effect.

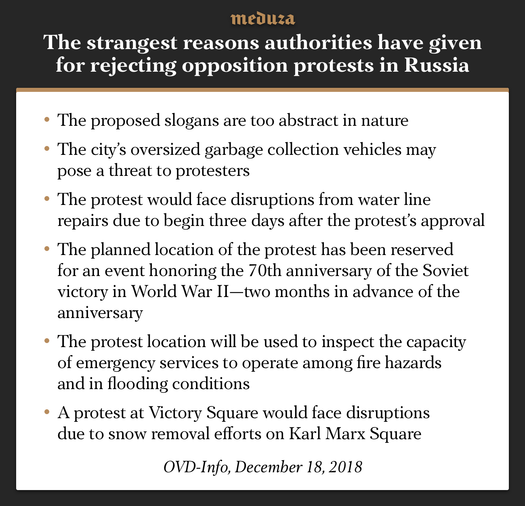

Protests can be rejected for reasons that are not listed explicitly in Russian law

Local governments in Russia have the right and the duty to evaluate whether the aims of a protest correspond with legal and constitutional norms. However, those norms can be interpreted very broadly.

In October 2012, for example, a group of Moscow residents requested approval for a picket in support of labor activists in Kazakhstan. They were told that the aim of public events in Russia must be for Russian citizens to discuss issues affecting their own country—a provision that exists nowhere in Russian law. The local administration in Saratov refused to sanction a different picket because “there is no picketable object, which eliminates the very possibility of picketing.”

In other cases, local authorities have attempted to use protestors’ rights against them. March 26 organizers in Vladimir, for example, were first notified that their request for approval was rejected because of a conflicting event. When they asked the local government to propose an alternative place or time, officials responded that such a move would “restrict [the protestors’] rights to determine the location of their demonstration.”

It is nearly impossible to hold local officials accountable for unjustified rejections

In addition to searching for data among community organizers, OVD-Info examined the protest approval procedure from the perspective of local bureaucrats. Between the moment a request is received and the moment activists receive a response, a range of officials come in contact with every case. However, attempts to hold any of those officials responsible for bureaucratic errors or legal violations nearly always fail.

Organizers who hope to reverse a rejection or ask that local officials face consequences for a bad decision have two possible paths: they can complain to the same government organ that issued their rejection or turn to a local court, but not both. In advance of the March 26 protests, a number of organizers took the latter route, asking courts to allow their demonstrations to proceed without being labeled illegal. The court decided in favor of the protestors only in the city of Novosibirsk. Attempts to sue or prosecute individual bureaucrats shared a similar fate: no local official in the Russian Federation has ever faced legal consequences for limiting freedom of assembly through the protest approval process.

In short

The ability local officials possess in Russia to determine whether events are “sanctioned” or “unsanctioned” may seem at best like a merely procedural power and at worst like a way to make sure opposition protestors receive the worst public reception and the most arrests. However, the OVD-Info report makes clear that this technicality can also prevent protest organizers from organizing in the first place. After all, activists can only begin planning and publicizing an actual event once they have jumped through every one of the hoops outlined above and many, many more. Since 2012, Russian law has dictated that no one may even share information about a public event until it has been approved by local authorities.

Natalya Smirnova and Denis Shedov, the authors of the report, conclude by reminding their readers that this means flashy news coverage of protests themselves only gives half the story: “Whether a demonstration is sanctioned or not,” they write, “determines the number of participants who are arrested and the protest’s image in the media. Nonetheless, the actual procedure that regulates that status usually attracts less attention and tends to remain in the shadows.”

Report summarized by Hilah Kohen