‘A mustachioed convict is nonsense’ Oleg Navalny’s first interview after going free from prison

Мы рассказываем честно не только про войну. Скачайте приложение.

On June 29, Oleg Navalny went free from prison. Like his older brother, Alexey Navalny (the activist who created the Anti-Corruption Foundation), Oleg was controversially convicted of embezzling several million rubles from an Eastern European subsidiary of the cosmetics company Yves Rocher. Unlike his brother, Oleg was sent to prison for three and a half years. (Alexey was sentenced to probation.) While behind bars, Oleg studied English and Spanish, learned to illustrate, corresponded with dozens of people, and authored several stories for Meduza. After he was released on June 29, he spoke to Meduza’s Andrey Kozenko about his time in prison and his plans for the future.

Oleg Navalny’s two sons, four-year-old Ostap and six-year-old Stepan, stand on each side of their father and hug his legs. “Where was Dad for three years?” Oleg asks them. Stepan gives the question some thought and says, “At work.” “And what was he doing at work?” Oleg asks next. “C’mon, I explained it to you yesterday,” he adds. Now the children get embarrassed and try to hide their faces. “Exactly,” he finally says. “For three years, your dad has been maintaining law and order at one of the regime’s restricted facilities in the Oryol region.”

“It was amazing how people could compare me to Lenin”

December 30, 2014. Moscow’s Zamoskvoretsky District Court. They announced the verdict and handcuffed you. What happened next?

It was hard to follow what was happening. I was riding in a police van, thinking that some dance of death awaited me, or that I’d have to fight for a bunk. They sentenced me at 9:30. Forty minutes later, I’d already been delivered to the Butyrka [detention center]. They said they’d been waiting for me for two days, though it had only been 24 hours since my sentencing date was announced. The main thing I was feeling was that I didn’t understand what was happening. I regretted that I hadn’t finished reading a book called “How to Survive the Penitentiary.” It had been dumb not to read it all right away, but I was always busy with something else.

Who were the first inmates you saw? You were put with both convicts and suspects, right?

The convicts were only there working as janitors. I saw this one really weird guy — the first real prisoner I ever met. “We’ve all already heard about you, Oleg,” he says. “Nice work! I’m the same.” I say, “The same what?” He says, “I’m from the Voronezh People’s Front!” I think to myself: “What front? What’s it got to do with me?” Then he hands me a mattress.

They already knew about me in there, and so they were nice to me. For some reason, one of the first things they told me was: “Eh, don’t worry. Lenin was locked up, too!” It was amazing how people could compare me to Lenin, and they kept repeating it: the comparison seemed perfectly logical to them.

You got there on December 30, just before New Year’s. That probably made for a pretty strange holiday?

Yeah it was very weird. They weren’t supposed to keep me in quarantine alone, so they brought me to a cell on a floor where the rooms were small and designed for four people, and they put a convict in with me. The door opens and he’s standing there, looking overwhelmed, holding a bowl of [holiday-traditional] Olivier salad. He probably had plans to talk to his relatives over Skype, hang out with his friends, and drink the moonshine they’d gotten from the prison staff in a trade. Now they’d taken all that from him. Not only had they brought him here and handed him a bowl of salad, but now I show up (whoever I am), saying, “Greetings!” We ate the salad, listened to the fireworks, and heard the other inmates celebrating. It was very weird.

How’d you cope with your life getting turned upside-down like this? You went from being free to living suddenly in a state of pretty intense subordination, where this guy or that guy is ordering your around, and you have to obey.

In some ways, that’s true, but you become part of a larger game. On one side, you’ve got the inmates. Out here, they’re criminals — murderers, rapists, and so on — but on the inside, they’re Vasya, Pete, and Potap. They’re your friends and your brothers in misfortune. The other team in this game is the prison administration. This is trench warfare and it’s fought in several different ways. One side tries to force the other to do something, and the latter tries not to do it.

Of course, it’s frustrating when Joe Schmo walks up and orders you around: Get up! Sit down! Hands behind your back! But it’s not a constant feeling of subordination; you feel like you’re in a game.

How did they get you to the penitentiary?

On February 17, [2015], my appeal fell through. They rejected it, though they revoked the fine against Alexey. According to the law, I was supposed to have been transferred to Oryol within 10 days, but they didn’t manage it in time, and it was two weeks before we left for Oryol.

They showed up at 4:00 a.m., explained how they’d be escorting us, gathered the prisoners together, and brought us to the train station. They loaded us onto a special iron train car, which was divided into different kinds of small little compartments.

It was iron from the inside?

There wasn’t a piece of wood on the whole thing. The aisle was a little narrower than usual, and the beds were three-tiered. Some of the compartments were bigger, and others were half-sized with just three beds on one side. The compartments locked with iron bars. Sometimes they stuffed as many as 20 people in one compartment, and people rode standing or they literally sat on each other. My setup was more comfortable: I spread out a little black rug they’d given me, and I read Jaroslav Hašek’s “The Good Soldier Schweik.” The part where he lands in prison is very similar.

We stopped in Serpukhov, in Tula. They unloaded some people and loaded others in their place. When we got to Oryol, we arrived first at the pretrial detention center. Then we came to the prison.

I saw it, the day you were released. It’s not the most uplifting place.

My first impressions were that it was very cold, it was snowing in light clumps, and for some reason there were hundreds of crows flying overhead. They’d come back early this year. Everything was gray, the prisoners’ faces were yellow and white, and they wore black jackets. It was all pretty sad, and I realized that I’d come to a very strange place.

The very first morning, they woke us up at 5 a.m. and said it was time for drills. So there we were, jerking our arms around and twisting our heads, as I tried to understand what was going on, as if it wasn’t happening to me.

Can you describe a typical day in prison?

They play the anthem at 6 a.m., and the duty officers come round to our block and tell us to wake up. After the anthem, they play a Vysotsky song about morning exercises, and then they break out this horrible techno music from the 90s. After fifteen minutes, it drives you completely nuts. According to the prison’s administrators, this is rhythmic music and everyone is supposed to exercise to it. Of course, nobody does. And it’s unclear how they could legally force people to exercise. Would they issue a list of approved movements, or something?

Next, breakfast is available to anyone who wants it. Everyone is supposed to eat, but in practice it’s not mandatory. They only force everyone into the mess hall when inspectors come through.

Then everyone heads to their work crews. This prison was one of three in the country, I think, that included both high- and minimum-security inmates. At seven in the morning, to the tune of “Farewell of Slavianka,” they march the prisoners to work. They take them down a long, narrow corridor from the living quarters to the production floor, in rows and columns. It looks like something out of the [computer game] Half-Life: a long corridor, maybe 600 meters [656 yards] long, narrow, and lined with barbed wire, and bars are sticking out.

But I never went there even once. When I arrived, they apparently decided that it would be bad to send me, in case I evaluated the working conditions from the perspective of work-space organization. They manufacture clothing there, and there needs to be fire safety and ventilation. They thought I’d see everything and start to raise hell. So almost immediately an eye doctor came by and said that I have bad vision, and he wasn’t lying. Then they issued me a certificate saying that I can’t lift heavy objects or work in dusty areas, although in reality they’ve got inmates who are half-blind working on the factory floor.

The inmates stuck in the residential area spend the whole day doing nothing. Some guys watch TV all day, and others just sleep. They do their own thing.

But it’s prohibited to sleep all day. Do the guards monitor this?

The staff isn’t big enough to keep an eye on everyone. They got one of the barracks ready for my arrival: they repaired it, stuffed it with surveillance cameras, and watched us remotely. They actually did monitor to make sure that nobody went back to bed. Well, they made sure I didn’t, at least. Sometimes they came after other inmates, threatening to write them up.

“There’s a handful of serious criminals, but it’s a very small group”

Oleg, how did you go from being this relatively privileged inmate to one of the most punished prisoners in the country?

What are you talking about?! I wasn’t even the most punished inmate in that town! I didn’t lose my privileges when they started [putting me in punitive confinement]. For the longest time, the prison administration didn’t know what to expect from me: would I [quietly] disobey them or would I tell everyone how things work on the inside? In the end, we both got used to each other. It was full-blown Stockholm syndrome, and it went both ways.

I think it generally started with the protest [on September 20, 2015, for peaceful transitions of power], where they played a recording of my address. That was a whole story. I called from a payphone, completely within my rights. The prison has the means to listen in on my calls, but I was always calling only my mother and wife, and it was all so boring to “Big Brother” and the “bloody regime” that they actually stopped listening. And it’s not like I was waiting for my moment. It wasn’t like that. My brother and I planned the call, I wrote out the speech, and I read it twice [over the phone]. The first time through, my brother said it sounded like I was reading from the page, and he said I needed to make it sound like a speech. So I put some feeling into the second reading, and the superintendent and his assistants came running. I was certain that they’d file a complaint, saying that I was making speeches and starting my big political game.

When they played the speech, it came as a total surprise to the Federal Penitentiary Service. They thought the fact that I’d used a telephone meant it was an illegal mobile phone, which would have made the whole thing illegal. Several of the prison’s managers were in danger of losing their jobs, and in the end they retaliated by throwing me in SUS [strogie usloviya soderzhaniya, or strict detention conditions].

Oleg, let’s take a second to break down some of these abbreviations. SUS, ShIZO, and PKT were all things that made it possible to isolate you more and more, while you were in prison.

Minimum-security prisons keep inmates detained in several different conditions. There’s the light version, where you get more allowances, you can buy larger items at the commissary, and you can ask to be transferred to a settlement-colony — stuff like that.

Strict detention conditions are when you’re in a locked room. It’s the same barracks, but the guards lock them shut. Inside your quarters, there’s a shower room, a kitchen, and you’re always surrounded by a ton of people. But because it was both a minimum- and maximum-security prison, this barracks also has PKT [pomeshchenie kamernogo tipa, or cell-type confinement], where you can read books and there are barred windows, double doors, and an attendant’s post.

ShIZO [the strafnoi izolayator, or punitive confinement] is almost entirely underground. You’re in the basement and there are bars on the windows near the ceiling. It’s a pit, basically. We called it “kichabur.”

Kichabur?

Yeah. It’s from the words “kicha” [prison slang for punitive confinement] and “bur” [prison slang for higher-security barracks]. The floors are wooden, the walls are concrete, and there’s a sink and a bathroom stall. At night, they unhook the beds and hand you a mattress. In the morning, you give back the mattress and the beds get stowed away again.

The biggest difference is when they stick you in ShIZO. They tell you it will be for 15 days, and time suddenly stops. You just sit there, counting the minutes. In PKT, on the other hand, you can get two months, or even six months, and you can make yourself at home. It’s a huge advantage to be in charge of your own time.

What lands prisoners in PKT?

The main reasons: if they find a mobile phone, if you talk back to the boss, or if they see you talking to a “thief in law.” They’ve got their own system to weigh what you can and can’t do, and it has nothing to do with the real rules; it’s all built informally. There are inmates who have spent the last eight years in PKT. I was there for my last few days on the inside, and I was with three prisoners, one of whom had been there for a year and was later transferred to a [higher security] prison, where they gave him another year in PKT. Another of the three spent two years in PKT. And the people who earn their cred in crime families are also frequent guests there.

How many times did you end up in PKT? What for?

That’s a long story. They disciplined me 50 times. There were constant transfers [from one kind of punitive confinement to another], and it wasn’t always clear why. Because I brought publicity to the prison, they decided to use me in some of their games. They’d come and say: Navalny is a lousy prisoner. He’s got too many books. His cell is messy. Off to ShIZO with him! Sometimes it was tied to Alexey [Navalny]’s activities, when I had no idea what they were. They’d just show up and tell me they’d been ordered to toss me in ShIZO.

The whole thing is complicated. For me, the last three years were like watching an art-house film: you don’t always understand what’s happening or where it might lead, and sometimes it’s not even clear who the main character is.

Ultimately, I just stopped being nervous. You’ve got to ignore everything you can’t control, and that’s exactly what I did.

And the other prisoners? Who were they? There was a Facebook page based on your letters from inside, where you repeatedly demanded the release of someone apparently named Kostya-Mogila [Kostya Grave].

It was Tolya-Mogila! I want the appeal for his release to be written separately.

I’d say that two or three percent of convicts are completely innocent. The authorities locked them up for their own reasons: someone was squeezed out of a business, there was an argument, or maybe somebody’s wife left one for the other. A good 70 percent land in prison with huge procedural violations in their cases. These people are guilty, but they end up behind bars with some disregard for the law. Some guys are there for things you’d never believe are enough to land you in prison. Like, somebody stole a bottle of vodka, or someone sneaked into an unguarded facility and stole two cast-iron sinks. And they put people away for a long time for that stuff: three or five years. There are a ton of drug users, too, but not dealers. It’s mostly ordinary people who smoke marijuana or use heroin or spice. There’s a layer of serious criminals, but it’s really small.

How did Tolya end up in prison?

Tolik was just this 17-year-old high school grad living somewhere in the Moscow suburbs. After the prom, already a little tipsy, he went to this bar, where he saw two big guys beating someone up, in some drunken brawl. He tried to break it up, and then the guys started beating him up. He tried to run away, and even jumped into a taxi and yelled something like, “Step on it, boss!” but they caught up to him and dragged him out of the car. Next, he says he hit one of them and knocked him to the ground. Then he hit the second guy and knocked him to the ground, too. It turns out that he killed the first one and seriously injured the other one. They gave him just five years because he was a minor.

He’s from a big family, and his mother actually got a state award for having so many kids. They’re all very worried about him, and they’re always coming to see him. He’s a good kid.

On an ordinary day, did you get along well with the others?

Yeah. I communicate well with everyone, and I never think somebody is too dumb to have a conversation. You get there and it’s like a commune. You talk to everybody.

Plus, everyone wanted to know who I was, and there were lots of questions. First and foremost, I was hounded by all these con artists and scammers: they’d heard the name Navalny, but nobody knew exactly who this is. Maybe I was a deputy or even an oligarch. That made me a money bag, and so they came at me right away, trying to sell me signets with Peter the Great and Genghis Khan, and oh yeah I needed to buy them right away. Or they wanted me to get in on some lucrative project to create a network of hair salons in Dushanbe.

How did you come to the conclusion that the best way to save yourself was by staying active?

The first time they put me in isolation, I realized that that’s what the rest of my three years would be like. I knew I’d go crazy, watching the clock while nothing happened. So I made a schedule, writing down everything I could think of: languages, sports. I designed it to be too much for any one person. This can really give you an extra boost and make time fly. I was always running out of time and putting something off until tomorrow, and the time passed faster. It works. I hope you never end up in any of these places, but if you do, that’s what you should do.

And what did you manage to learn in three years?

I got a correspondence education in law, and now I can read Spanish. When I settle back into things, I’ll find a tutor on Skype and learn how to speak it. I wanted to do Portuguese — the writing is very similar to Spanish, but the pronunciation is totally different. But I couldn’t find a single native speaker around me, so I decided to put it off. There was a tutor in English, and I corresponded with a mathematics professor in Kazan, and with a girl who helped me with my drawing, giving me assignments, correcting me, and telling me what to change. So I did a lot of drawing. And also origami. Plus, a lot of people wrote to me, and I answered every letter. This was also a good way to spend my time. I exercised for three hours a day, doing push-ups, squats, and lifting a 20-kilogram [44-pound] water tank.

Oleg, can you say a little more about the letters from the outside? Were they really that important to you? There were probably 20 times that I started writing a letter to you that began: “Greetings, Oleg. This is Andrey. Everything’s good with me. I moved from Moscow to Riga. It’s interesting here…” And right about then, I’d imagine your prison cell and think of you sitting there, reading this letter, and thinking to yourself something like: “So you’re in Riga now. Congrats. I’m ‘glad’ that you’re leading such an interesting life out there.” And then I’d just put down the pen. I didn’t know what to write next.

You shouldn’t have stopped. I know how hard it is to write those letters. I wrote them myself to [filmmaker Oleg] Sentsov, [former Kirov Governor Nikita] Belykh, and others who have been locked up because of politics. Yes, it’s totally impossible to know what to say to people in our circumstances. But it’s much easier to respond: you just comment on what was written, ideally with some irony. And then everybody loves you. They say, oh what a witty, cheerful guy.

Here’s what you should write about [in letters to inmates]: places you’ve been, what you saw, interesting articles, and news. A stream of consciousness is totally fine. That’s how you find out a little about what’s happening not just in your little world, but somewhere else. I think anybody in my place would have felt the same way. So it’s a shame that you didn’t write down what you were up to in Riga.

“Don’t trust the mustachioed”

How’d you spend your last few days in prison?

I expected the end to go the slowest. I thought it would be impossible to wait any longer. The first day and the last day are like that — that’s what everybody says. But it wasn’t like that at all. Time flew because I had a lot of things I needed to finish up, plus there were all the lawsuits against the prison administration; I’m appealing every single violation they pinned on me.

The first time they slapped me with a penalty, I told them: I’m challenging this one and any more, no matter how many there are.

So I wasn’t too high-strung. On June 29, local officials from the Federal Penitentiary Service were worried that a crowd would come and there would be a demonstration and possible clashes. So they released me as early as possible: around nine in the morning, though inmates are usually registered and discharged around noon.

Not much of a farewell.

Yeah. Also, they were recording me on four video cameras: from the exit to where they returned my personal effects, including my 2,000 rubles (about $30).

I guess the last month felt a bit long. They moved me again to PKT, and I was there with two other guys. They told me how to guard against pickpockets, and I taught them what I’d learned from the “Physics of the Future.” It was an alright time.

When you were still inside, you wrote a text called “How to Serve Time in Prison” for Meduza. I thought you’d walk out juggling 12 aluminum mugs, but instead you looked a bit overwhelmed.

Well, everyone was looking at me and taking my picture. I’m not a public person, and I don’t know what to do or what to say. All I wanted was to go home. My friends and family came to meet me, and I wanted to hug them, but not on camera. It was an intimate moment. Then we finally got going.

What’s the story with the “ritual” you staged on the way back home?

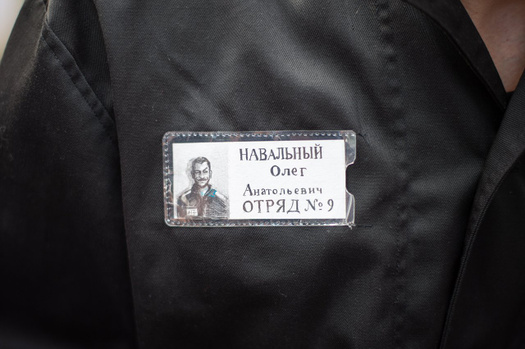

Prisoners say you’ve got to torch your uniform, after you get out. So we found an open field and did it there. I think it’s a good ritual. I’m all for it. Admittedly, it was made from some kind of plastic and it didn’t want to burn. We spent an hour keeping it on fire. Then we poured water on it, so the fire didn’t spread to Oryol’s fields, and then we finally went home.

How have your first few days of freedom been?

I can finally breathe again. It’s euphoria. I feel like prison was already a long time ago, like it’s been 10,000 years since I left. Everything that was there is over and done without a trace. I’m not looking out into the distance, remembering the horrors and hardships. It’s great here. The weather is terrific, and I’m surrounded by loved ones. You and I are sitting here, chatting and eating cherries. I’m in ecstasy just thinking about these little things. And I’m still waiting for my wife to bring me a razor, so I can finally shave off this mustache.

I wanted to ask if you really planned to keep it.

Oh, I’m totally sick of it. Never trust the mustachioed — they’re all suspicious.

But there’s an important backstory for me here. There was this guy named Afanasyev — he was the warden, and they replaced him after the whole thing with the rally. I get there and they hit me with the first penalty within a week, and it becomes clear that that’s it — there’s not going to be any early parole, and the crackdown is coming. It’s all bad. And this Afanasyev was the type who wanted you to know where you’d landed. But I started understanding even less where I’d ended up and why. And I started looking for loopholes in the prison’s internal regulations. I found one document that described “a short beard and mustache.” So it turned out that mustaches were okay, and I said to myself: wow, I guess I’ll look like ZZ Top. Afanasyev really wanted to make them shave me, but I resisted. He said: We’re going to use physical force. I said: Go ahead. But they didn’t dare. I just couldn’t imagine them beating me and shaving me all at the same time.

I styled my moustache in several different ways, including like a Canadian lumberjack with side-burns. I spent a year growing this mustache; it’s gotten so long that I can twirl it on my finger. I was the only inmate with a moustache. A mustachioed convict is nonsense.

For me, it was a way to feel free again.

Oleg, I apologize if this is a hard question, but I want to ask about your family. You lost three and a half years in prison thanks to a politicized case, but this is also about your kids. They were left without their father for all that time. How do you make up for that?

I can’t. There’s no getting back the time that was lost. I can’t do anything about that. I only just met my [younger son] Ostap. When they locked me up, he was only 10 months old. I saw him when he was two and a half, and he could already talk. He said, “Hello! Are you my daddy? Does that mean I have two daddies?” I froze at first, but then I understood! At home, when they talked about me, sometimes they said “daddy” and sometimes they said “Daddy Oleg,” and so he decided that this must be two different people. My older boy came up and hugged me, and said, “I love you.” I think this has caused them some trauma, but it could have been worse. My brother was with them, and so was their grandfather. But someone should still have to pay for this. I’ll be making special plans on that score.

You’ve always said as much, never talking about forgetting or forgiving anything.

I remember this one time when I was sitting there, writing a letter to [my wife] Vika, and I said, if I ever told her even once something like, “Oh well. Three years have passed. Let it be. That’s just how it goes. Why try to get even?” then I wanted her to remind me how horribly cold I was in April 2016, when they shut off the heat and the temperature plummeted. I slept in a pull-over and I kept waking up because I was so cold. I was absolutely furious. Why should I have to be so cold, when I didn’t do anything to anybody? I can tell you with absolute certainty that I’ll make everyone involved pay for it, if I ever get the chance.

Interview by Andrey Kozenko, translation by Nikita Kharchenko and Kevin Rothrock