‘These are our kids, and we have to help them’ An inside look at the criminal network sparking new fears of youth violence in Russia

Мы рассказываем честно не только про войну. Скачайте приложение.

In recent months, Russia has seen several adolescents carry out armed attacks against schools and their students in locations as disparate as the Moscow suburb Ivanteevka, the regional center Perm, and a village near Ulan-Ude in the Chelyabinsk region. In almost every case, media sources, government agencies, and investigative organizations tied these events to “AUE,” a criminal movement that allegedly targets adolescents. The abbreviation is usually expanded as “Arestantskoe Urkaganskoe Edinstvo” (which translates roughly to “The Prisoners’ and Gangsters’ Union”) or “Arestansky Uklad Edin” (“the Prisoner’s Lifestyle Is Unified”). Russian Senator Anton Beliakov has even responded to rumors about the movement by proposing a prohibition against “propagandizing criminal subcultures.” Opinions about what AUE actually is diverge widely; some call it an informal societal movement, others describe it as a social structure parallel to the government itself, and yet others believe it is a simple greeting that is common in criminal circles. Meduza special correspondent Sasha Sulim traveled to the Irkutsk region, where she found both adolescents obsessed with the culture of AUE and police officers who combat it. Sulim’s story was translated into English by Hilah Kohen.

The names of several sources in this article have been changed at their request.

“Robbery is a lyudsky way of life,” explains Mikhail, using a term that, in Russian criminal culture, has come to refer to unusually “orderly” or organized lawbreakers. “But you have to ‘allocate’ part of the sum that you stole to your ‘elder,’ and then he’ll give you ‘protection’ — in case someone from the other neighborhood comes along.”

Mikhail is 18 years old, and he has spent his entire life in Ust-Kut, a Siberian town of some 40,000 people, about 500 kilometers (310 miles) north of the regional capital (Irkutsk). The young man, with his below-average height, looks younger than he is; he wears a tracksuit and thin Keds over thick winter socks. As he walks into the warm room where he will speak with Meduza’s correspondent, he pulls a knitted cap onto his head, and his uncut dark hair sticks out from underneath. He repeats the word “udeliat” (to allocate) several times during the interview. He’s referring to the act of sending tea, cigarettes, or money to “the zone.” He’s talking about sending care packages to prison inmates.

In the fall of 2017, Mikhail and one of his friends robbed more than a dozen stores. They also stole wheels and batteries from trucks and broke into apartments. In December, the young men were arrested, and their trial is now underway. A source within a human rights advocacy group in Ust-Kut confirms that Mikhail and his friends adhere to “the ideology of AUE.”

The young man describes one of his first encounters with the “elders” of his neighborhood as follows: “They told us, ‘You can come to us, we won’t pressure you, but there’s one condition: whenever you can, help ‘our people’ out.” He explains that “our people” are criminals imprisoned in Ust-Kut and Angarsk. “All the guys agreed.” According to Mikhail, his friend Nikita, the de facto leader of his group, was “put on the money” by a “supervisor” after Nikita robbed a store on the supervisor’s territory. Nikita was given four days to pay off a debt of more than 100,000 rubles (more than $1,600). The entire band decided to help. “The money we took from the stores went to pay off the debt, and the tea-smokes [tea, cigarettes, and other stolen products] went to the zone,” the young man says.

Another member of the group, Sergey, clarifies that everything the young men stole from the stores and sometimes from their own homes was handed over to Nikita, who became one of the neighborhood “supervisor’s” right-hand men. Whether the supervisor in fact sent any money or cigarettes to the zone is unknown. A source in the human rights advocacy community of Ust-Kut told Meduza that the supervisor is now being held in a pretrial detention center and investigated.

Sergey is the youngest member of the group: he is in the seventh grade. Like his friend, Mikhail, he lives in a privately owned home in the neighborhood of Old Ust-Kut. Sergey wanders the streets in a tracksuit with a vest worn over the jacket. In his words, AUE is a greeting used by those who are drawn “to the lyudsky way, to thievery.” He knows that it stands for “Arestantskoe Urkaganskoe Edinstvo,” but he cannot explain who “urki” (the root of “urkaganskoe” and a criminal slang word for thieves) might be. “You steal stuff, you send it to the zone, and when the guys go free, then they’ll start helping you,” Sergey explains confidently.

The court of Ust-Kut sentenced Sergey to nine months in an alternative school in Irkutsk. The young man has been in the capital before only once, having spent three days here in a pretrial detention center after his arrest in December. He speaks about his upcoming time at the alternative school only grudgingly; he prefers to imagine a more distant future. Sergey dreams of serving in the army and then hopes to work as a driver. He learned to drive several years ago and has more than once gotten drunk and taken a spin in his father’s car. “His mother and father are always at work. They’d never watch him, so off he goes to look for something new,” the human rights worker says about Sergey. He is sure that the boys were forced to steal and “allocate” their bounty, and they’re just too afraid to admit it.

Mikhail is the only member of the group who faces the threat of an adult prison term; his friends are all younger and were charged as minors. “I’ve become totally domesticated. I only go out to work — I help road maintenance crews as a volunteer, for the good of the city. I’m going to stay put here until summer, until the trials are over, and then I’ll take off for the countryside. I have a place to stay there, a house where my uncle lives alone,” Mikhail says about his life during the trial. He looks sadly through the window, his eyes following a woman walking by. “I just feel sorry for my mother. My father has gotten so lazy — he doesn’t do anything around the house. He just drinks, yells, and throws himself at her.”

Mikhail, Sergey, and the rest of the gang all live in Old Ust-Kut, a neighborhood that used to boast the highest crime rates in the city, according to a source in the local police department. “Serious crimes,” the source explains, “occurred here at double the rate of other neighborhoods,” but things improved after the arrests of local “supervisors.” But the problem of youth crime persists, Meduza’s source says: “Kids here don’t have anything to do, there aren’t any rec centers, and their idleness leads them to these thieves and to getting obsessed with AUE.”

Ust-Kut has a rich history of ties to the criminal world. In the 19th century, the town was a final destination for many Tsarist political prisoners. Participants in the Polish uprising of 1863 and even Lev Trotsky himself were imprisoned in Ust-Kut. In the Soviet era, the city was practically overgrown with jails. Two prison colonies and one high-security penitentiary were located nearby. Now, only a temporary holding area and one prison colony remain. “Out of every ten people here, seven are convicts, and the rest — if they aren’t convicts today, they will be tomorrow,” explains a policeman. In his words, it’s difficult to find a family in Ust-Kut without someone who’s been through the prison system.

Rehabilitation in the graveyard

“When the harsh frost hits, when it’s minus 40 outside, we have to get up and dig. In the pit, at a depth of about a meter [3.3 feet], it can actually get too hot — and that’s what saves us,” says 27-year-old Igor as he puts on a camouflage uniform covered in soot. He pulls on a balaclava, so the ash doesn’t reach his lungs. All this is necessary for his work: Igor is a gravedigger in one of the graveyards in Ust-Kut. Before he digs a grave, he has to burn enough lumber to warm the earth below — hence the ash. Digging alongside Igor is his mentee Nikita, the same 16-year-old who was indebted to a supervisor and for whose sake Mikhail and Sergey robbed stores.

The graveyard is located in a pine forest. Nikita’s father, who is unemployed, drives the young men to work (it’s not easy getting around in Ust-Kut on foot — the city stretches along the left bank of the Lena River for almost 40 kilometers, or 25 miles). In the middle of March, the gates and monuments are still layered with snow, and only the bright colors of artificial flowers give away the fresh graves in their small clearings. “Now we’ll sweep out the soot and start opening it up,” explains Igor. “The first half meter is easy to get out, but then, when you have to clear out frozen soil, you’ve got to apply some force.”

At one point in his life, Igor was a serious boxer, but an athletic career never took shape for him, and he became deeply involved in the criminal world. “Everything started with weed — I had my first smoke when I was 11. Then, I started going out with the guys to harvest it — there were whole thickets around the city here,” he recalls. “After a few years, I could already get to ‘serious people’ through my acquaintances if I wanted.”

Igor’s mother lost her parental rights early in her son’s life, and he spent his childhood “on two fronts,” as he now puts it — both with his mother and with his grandmother. “These guys [Igor’s mother’s suitors] would get out [of jail], come to us, get shitfaced with my mom, and threaten me with a knife,” Igor says. “I got on the list at the subdivision for minors’ affairs early — for the drug therapist and the psychiatrist. They thought I was an idiot — brought me to the nuthouse three times.” In high school, the young man became obsessed with theater and played in a rock band, but his relatives and his teachers showed no interest in his life. But “serious people,” Igor says, looked after him on a regular basis: “It was like they actually cared about what was going on in my life. That’s how I fell into this thieves’ romance: I’d help them, and they’d help me.”

In Igor’s words, his activity included drug dealing and much more — he didn’t just deal in “major real estate and cars.” At the time, he was only 15, and he could already speak without a middleman to “whomever he needed.” “You start dealing with serious issues, and people ask you, ‘What do you live on?’” Igor explains. “And back then, I ‘muzhiked’; that is, I worked, I took care [of prisoners], and I didn’t cause trouble.” At some point, he began using hard drugs and “completely lost control” of his actions. At 20 years old, he ended up in an IK-14 forced labor camp, after being sentenced to two years for armed robbery.

Igor learned about AUE long before he ever landed behind bars. “People told me when I was free, ‘You allocate, and then, when you ‘go out there,’ you’ll already have an advantage in the zone,” he remembers. “And when I got to prison, all the people I had been helping that whole time didn’t even say a word to me.” At one point, the young man lost a card game, and even his friends who were free were unable to help him. And in the zone, “losing and not paying your debt is even worse than being a faggot.” That’s when Igor turned to “the believers.” “They worked in our industrial zone,” he says. “They told me, ‘We can’t help you with money, but we’ll pray for you.’ I started praying, too: ‘God, if you exist and if you are who they say you are, truly, help me now, I promise, I’ll follow you.’ Believe it or not, I figured out that question the same day — a friend of mine sent me 2,000 rubles [almost $33].”

Upon his release, Igor began regularly attending church services, but he turned off “the path of truth” relatively quickly, returning to his old group of friends and using drugs again. “At some point, I realized that I wouldn’t survive if I kept living that way,” he says. “I came here and set up shop in the graveyard.”

As Igor speaks, he catches his young partner listening carefully to his story. “Eavesdropping are you?” he tells him. “Grab the shovel and get to work!” The ninth grader Nikita became his apprentice a week ago — he, too, is trying to mend his ways. “We’re neighbors — he grew up before my eyes,” Igor explains. “I saw the company he kept and the places he was going. I tried to talk with him about AUE, to explain that ‘allocating’ and stealing money is just spreading lawlessness.”

Nikita himself categorically rejects his ties to AUE: “I’m not about that, I don’t follow the lyudsky rules or the criminal ones, and I don’t allocate anymore.” He says he learned the meaning of all these words on the Internet: he saw graffiti with the letters “AUE” in town and joined several groups on the social network VKontakte. “All the punks out here screamed about this stuff — they’d yell, wave their arms, but they don’t know what on Earth it is,” the young man says. “And I yelled all empty-headed myself, just flapping my lips.” He says adamantly that he never sent anything to prisoners, claiming that he robbed stores with his friends out of sheer stupidity — “without any planning,” he says. “We were just walking by.”

Today, Nikita has stopped talking to his old circle of friends. He created a new Vkontakte page without ties to AUE groups, and he has the same ambitions as many of his friends: “I study at a night school, I work, I want to join the army, and then I want to go to sailing school and become a navigator.” A source in the local police department informs Meduza that Nikita is at risk of receiving a serious prison term in a colony for minors.

For each month that he works in the graveyard, Nikita receives around 30,000 rubles (about $490) — no small sum in Ust-Kut, where his mother, who works as an elementary school teacher, earns 10,000 rubles less, and his father is currently unemployed. “Bandits have an easier time getting money, but it all comes back to them eventually, like a boomerang,” says Nikita, his fingers fiddling nervously with an outdated mobile phone.

Of the 130,000 rubles that Nikita allegedly stole, he spent nothing on himself. According to a local police officer, “some of these guys had their stolen goods just lying around at home, but the money they took was never found at all. We don’t know what they spent it all on in such a short amount of time.” A few members of the gang told him that they gave what they stole to the elder, and he sent it all to the zone. However, in the trial documents, the abbreviation AUE never appears at all. “They didn’t tell the investigator that they were tied to AUE, and the investigator’s job is just to discover the crime and improve his case statistics — it’s not important why suspects did it,” the policeman says. “Officially, there is no AUE in this town.”

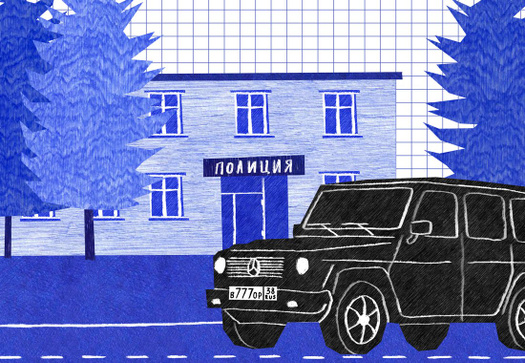

The chief of police in Ust-Kut, Yuri Kitsul, tells Meduza with confidence that, according to his investigations, “the AUE movement has not appeared in our town at all.” “It doesn’t survive here, we keep it in control, we check all the social media sites, and we talk to the parents,” says Kitsul. He adds that the youth crime rate in 2017 was almost 92 percent lower than a year before. Kitsul blames the media for all of it, explaining that the adolescents questioned by police say they first learned about AUE from the media.

“We don’t have gangs who get together to commit extortion — we don’t even have any organized crime in Ust-Kut,” Kitsul says firmly. “There’s no leader — we put everyone in jail. And nobody wants to take their place.” He claims that even AUE graffiti is absent from the city, although Meduza sighted precisely those three letters on the gates surrounding a house where, according to town residents, the boss of one of the local prison colonies lives.

“We don’t have AUE in this region because we put a stop to all that,” one of the local prison settlements’ “enforcers” tells the policeman. “We went to the young guys helping us and asked them to have a serious chat with the AUE people, to tell him that it would be good for their health to stop shouting this word.”

The enforcer and other criminal authority figures meet with Meduza in a small roadside café. They arrive in an enormous SUV with a bodyguard — a man of impressive dimensions wearing a leather jacket and several gold signet rings. The men place several telephones and a radio on the table in front of them (cellular signals can be spotty in the northern Irkutsk region). They say that intentionally attracting “youngsters” to the criminal world is frowned upon in their circles. They believe that young men should come to the world of thieving on their own.

“These AUE people spread a criminal mentality without ideas and without understanding,” the enforcer says angrily. “I mean, our kids also go to school! Do you really think we’re going to send someone there to shake them down for money? We live by rules — we’d never steal from an old woman, a friend, or a child.”

Prisoners’ justice

At a meeting of the Presidential Human Rights Council in December 2016, Executive Secretary Yana Lantratova called the spread of AUE’s ideology “a national security problem” that requires “immediate action.” Lantratova told Vladimir Putin, who was present at the meeting, that Russian prisons house people who set up “their own systems” in alternative schools and boarding schools through AUE “supervisors”: they force adolescents to give up money for the sake of the organization and refer to those who cannot chip in as “the discarded.” She added, “The most frightening thing, Mr. Putin, is that when they get out of these alternative schools, there will be a whole army of them.”

According to Lantratova, AUE was already widespread in schools and boarding schools a year and a half ago in 18 regions of Russia — in Buryatia, Transbaikal, Stavropolsky Krai, the Chelyabinsk region, and so on — and there were an “enormous number” of social media groups dedicated to the movement, publishing “videos with a very high production quality.” “They have their own recorded soundtracks, their own songs, and their own souvenir merchandise, which we understand to mean that there are substantial funds and highly interested people behind all this,” the human rights advocate argued.

An adjunct at Rostov’s South Russian Institute of Management who works on Russia’s youth criminal culture, Yuri Blokhin heard about AUE’s spread among young people outside the prison system in 2016 from a human rights advocate in Irkutsk. In recent years, he says, these three letters have also appeared in Rostov in the form of graffiti on roads and even on the door of a police outpost. Blokhin says he sees nothing new in the AUE subculture itself, describing it as just another name for a thievery movement that emerged in the Soviet Union in the 1930s and attained widespread influence in the years of post-Stalinist amnesty measures. Blokhin says “one of the functional obligations of the ‘thieves in law’ is recruiting young people, and showing them the prisoner’s lifestyle.” Today, he says, that life can attract not only ex-convicts but also musicians or social media users.

“So I was released, I went to meet my friends, and everyone just wanted to hear about the zone. After all, in Russia, it’s not just criminals who want to be bosses — businessmen and cops like that kind of influence, too. It’s all a kind of romance — they want to show off for the ladies. Everything starts with that,” the singer-songwriter Vladimir Kursky told Meduza. He encountered the abbreviation AUE as early as 1998, when he was serving time in a juvenile prison (the 35-year-old musician now has four convictions and has spent 10 years in jail). He argues, however, that there is no such “movement” or “ideology” as AUE — “there are just the same lyudsky standards or thieves’ traditions,” he says, adding that any “decent inmate” ought to support these traditions and pass them onto the next generation. But not everyone gets this right: “A lot of people start smearing all that into AUE and saying, ‘You have to contribute to the group,’ and then they just lap up the big bucks themselves — it’s corruption.”

Yuri Blokhin agrees that there is nothing qualitatively new about the AUE ideology. “It’s just that today’s criminal movement has taken on a new, more structured organizational form; it has latched on to a fashionable name,” he explains. “And young people outside the prison system have taken an interest in the ideology of organized thievery even if they have no ties to the criminal world or to centers of incarceration.” Blokhin says surrendering money to the collective is one of the fundamental bonds that holds the criminal world together: “Those who are currently imprisoned are traditionally considered victims in need of support. The thing is that the funds meant for paying lawyers or buying tea and cigarettes — if they even get to the zone at all — are spent on drugs or bribing prison administrators.”

Another former prisoner named Mikhail Orsky, who served three prison terms and wrote a book titled The Path of a Russian Gangster, says gangs have collected money from schoolchildren for decades. He claims that Russia’s criminal movement relocated to Georgia during the Khrushchev era, when the Soviet authorities instituted the practice of “breaking” organized criminals (forcing them to renounce their lifestyle on the day of their release and reconvicting them on new charges, if they refused). “And there, in the 50s and 60s, people started fundraising for the criminal collective,” says Orsky.

Both Orsky and Kursky say they’ve heard nothing about current happenings in Russian organized crime, and Orsky claims to have learned about AUE from the rapper Zhigan: “When they locked him up for a few months, I called him, and he yelled ‘AUE!’ into the phone.” Orsky is certain that no criminal organization in Russia recruits adolescents by force; the youngest member of his group is 33 years old, and he knows of others where no member is younger than 40.

The retired gangster, as Orsky calls himself, is sure that the spread of abbreviations among teenagers is some blogger’s doing. “I don’t think someone organized all this specially. AUE probably spread on its own,” Blokhin agrees, citing the Russian government’s unsuccessful youth policies as another reason for the “movement’s” popularity: there’s simply too little for young people to do.

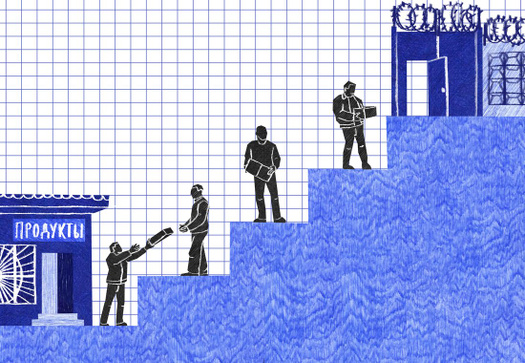

Socioeconomic problems also increase the number of AUE adherents: the subculture “is common in regions with a low standard of living, in places far away from large cities, and in villages with large numbers of young people,” says Blokhin. The philosophy of the criminal world, he adds, presents itself in opposition to government politics, which can also seem attractive to teenagers: “According to this ideology, the representatives of the government are corrupt, they’re garbage — they’re filthy wolves. In a life that’s built on the law, there’s no justice, so you have to take justice into your own hands because you can’t expect anything from the government.” Finally, in a criminal subculture, as opposed to regions with a low standard of living, there is social mobility: living by the principles of AUE can also be a chance to build a career.

“There’s more order in the world of organized thievery than in the world of bureaucrats who rob the people — the world of those pieces of trash who profiteer and cover it up,” says Kursky, the singer. He says all “decent” people both outside and especially inside the prison system ought to follow a defined set of rules; for example: “You can’t just insult or hit someone for no reason — that’s an unjustified move, and you can be kicked out for that.” These prohibitions also stretch into the realm of collaboration with criminal administrators: ratting out someone who is hiding a telephone, a blade, or tea “just isn’t how people are supposed to act.” Kursky is certain: “The top quality of any thief and decent person is honor.” His rules also say that contact with “faggots” — including sharing a table, drinking tea, or shaking hands — is prohibited.

Long live the thieves

“Here, AUE is a way of life,” says a police officer in Angarsk, a city six times bigger than Ust-Kut and 10 times closer to Irkutsk. The policeman first encountered the local criminal subculture when he was a child; he is now slightly over 30. “In the mid-1990s, my cousin, even though his father was a major in the police, got involved in AUE,” he says. “I remember how he told me about the time he was sitting in some basement with the local ‘authorities,’ and they told him that he would be a respected man in prison, if he butchered a cop, even if it were his own dad.”

As the policeman remembers, it was fashionable in Angarsk in those days to “act like a con”: young men shaved their heads, walked around with boom boxes playing criminal songs at full volume, and wore striped quilted jackets that looked like prison uniforms. He says the trend didn’t reach other cities in the Irkutsk region.

Like Ust-Kut, Angarsk’s history is closely tied to its prisons: the city was built immediately after the Second World War by prisoners of the Angarlag Gulag complex. Today, six prisons surround the city: four correctional colonies, an investigative isolation facility, and an educational colony for minors. Since the Stalin era, inmates released from nearby prisons have often “settled down” in Angarsk and remained convicts in their everyday lives, a local policeman told Meduza. “In other words, if someone called them, say, a ‘jackass,’ then, in order to retain their honor, they would find a knife and stab that person,” he says. “The next generation grew up in that environment, and over time, that generation also ended up in the [prison] colony, and everything kept on going.”

In the 1990s, criminal wars broke out in Angarsk and in many other Russian cities. In Angarsk, a city of about 260,000 people, there were about a dozen gangs. The police officer says his cousin ended up in one of them, and his status was the lowest in the criminal hierarchy.

As the police officer explains, the highest criminal status in the city belongs to the “enforcer,” who is selected collectively by criminal authorities throughout the Irkutsk region. The leaders of the Angarsk gangs report to the enforcer (there are currently five such leaders), and their money is collected by people at different levels of the hierarchy. The leaders set aside some of these funds for the group, with most of the money going to packages for inmates (both legal and illegal). The leaders have deputies — one might be responsible for the leader’s safety, another for “the forest” (the gang’s armory), and a third for the group’s finances. The deputies each have a few dozen assistants, or “thugs,” and they are the ones who take part in the actual “fundraising” effort: they escort logging trucks, control a stock of timber, and demand money from the owners of the logging enterprise.

The policeman says almost every gang has its own private security enterprise that “offers” protection for 3,000-10,000 rubles (about $50-$160) per month. Finally, the lowest rank is occupied by “strivers” — young men between the ages of 15 and 25 who are not yet official members of the criminal organization but who dream of joining and who receive no money at all for their criminal activity.

The police officer who spoke to Meduza says he believes that the ideology of AUE is meant precisely for young people, though he also says he doesn’t think criminal organizations intentionally recruit young people. “Each person decides for himself which laws he will follow: the government’s or the thieves’. The only whore you can force to work the highways is a highway whore.” He says “supervisors” don’t stoop to recruiting and raising funds in schools, and if their subordinates do so for personal gain, they can be punished.

The Angarsk officer first saw the letters “AUE” in a set of text messages exchanged by criminal suspects in 2013, before the abbreviation became well-known throughout Russia (he did not specify how he gained access to this correspondence). The three letters functioned as a kind of greeting in the messages, which usually contained information about the movements of “thieves in law” between prison colonies. One of the messages read as follows: “A.U.E. Long live the thieves! Dear friends, we greet you warmly and announce that today, Sept. 14, ‘13, in the Seaside Division at lunchtime the thief Andrey Hamlet was transferred to the Vladivostok Public Security Police. The thief is currently in the Therapy Box. May God grant the thief good health and a long life! Sincerely, Nimble and Plump.”

In juvenile prisons, newcomers are greeted with the same abbreviation. When they arrive, the policeman says, some “strivers” try to heighten their status by refusing to cooperate with prison administrators or by refusing to attend school or work. In return, they receive demerits that prevent them from being released on probation.

“At one point, we were working on a gang where there was an eleventh grader who really wanted the life of a thief in law, who would do anything to show that he was worthy of being a bandit,” the police officer says. “The more senior gang members noticed his efforts: a guard working for one of the ‘deputies’ asked the kid to be his ‘youngster’; that is, to work in his name. And this young man, who had a normal family with a car and a house, started selling marijuana. He did well, and after some time, they gave him his next task: running a protection racket for prostitutes. And then they told him to ‘come down on’ one of the prostitutes — to teach her a lesson with a beating. But these guys — he wasn’t alone — went too far, the prostitute couldn’t hold on, and she died. And so this ‘striver,’ who was really a normal guy, descended to the point of committing murder.”

You can’t rehabilitate these ones

Human rights advocate Vedeney Tyutiunin has heard the greeting “AUE” in the juvenile correction facility near Angarsk multiple times. Tyutiunin says the teenage inmates would greet him this way, when he came through as part of a public monitoring commission, even in the presence of Federal Penitentiary Service officials.

“I asked some of these guys, ‘What does AUE give you? As it turns out, they believe that when they’re released, someone will be there to meet them, someone will help them, and someone will give them money,” says Tyutiunin, who has regularly visited the prison in Angarsk since 2016. These people tell him that, without AUE, they simply wouldn’t survive in the colony: “This is how they pit themselves against the system: there’s an order, a daily schedule, and then there’s their culture, which exists to spite all that. If you want to be ‘straight’ (someone with a good reputation), then you’re supposed to live by AUE’s principles.”

The human rights worker says much of the responsibility for the spread of AUE lies on the shoulders of prison staff, who are accustomed to running the institution by force alone. “Most everyone there talks like this: ‘You can’t rehabilitate these ones. The only thing that works for them is a bullet to the head.’” Sviatoslav Khromenkov, an Irkutsk human rights advocate and the acting director of the Siberian Human Rights Center, confirms Tyutiunin’s observations. He says those who serve time in juvenile facilities often leave those institutions embittered and go on to commit more crimes. “In 2016, several complaints about unusually cruel disciplinary mechanisms reached us from the prison,” he says. “Soon afterwards, a young man who sent one of the complaints was released, and not long after that, he brutally attacked a police officer with a knife in Bratsk.”

Khromenkov says the Angarsk facility’s extreme disciplinary mechanisms lead to prisoner riots almost biannually. In 2015, when prisoners armed themselves with wooden sticks and metal pipes and started beating each other and members of the staff, the prison’s leadership responded by saying that the inmates believe “they are superior, that they can do anything without being punished.” Khromenkov says the prisoners were actually trying to attract the attention of human rights advocates. Public monitoring commission researchers found that prisoners over the age of 18 colluded with their guards to torture younger prisoners. “Eighty percent of the kids who are locked up there come from orphanages or broken-up families, and there just isn’t anyone who can stick up for them,” Khromenkov explains.

After an investigation by the monitoring commission, the prison’s warden was replaced and more than 20 Federal Penitentiary Service staff were disciplined, but the guards who’d bullied the teenage inmates held onto their jobs. In December 2017, twenty-three of the inmates who rioted had two to six years added to their sentences.

In May 2016, at the prison administration’s request, Khromenkov and his colleagues ran a seminar for 75 inmates, trying to cultivate “an adequate vision of the world,” to encourage people to welcome the chance to cooperate with prison staff in order to regain their freedom. Khromenkov says he never once heard the abbreviation “AUE” during these training sessions, but some of the boys clearly maintained their “unlawful direction” and continued to resist the prison’s rules.

Khromenkov says young people in Irkutsk are also drawn to criminal subcultures outside the prison system, even though AUE is composed largely of the same older thugs who extorted money from businessmen in the 1990s. “Lantratova is right to say that it’s time to sound the alarm. But the alarm should sound different: we have to fight AUE not because it’s an organized attack on our society but because these are our kids, and we have to help them,” he argues. “Creating and spreading myths about AUE only divides our society into those with power and ordinary people.”

A failed man

In his youth, Vladimir Martusov watched The Godfather at least a dozen times. “He loved how they showed the family — the relationship between the father and the son. And I guess he decided that he wanted to make himself a family just like that,” says his mother, Elena Martusova. Formerly married to a major investor in Angarsk, she led the business with him for many years. “And then my husband became one of the New Russians,” says Elena. “He started taking lovers, and the paranoia and persecution mania began.” That’s when Elena decided to file for divorce. In the end, their older son Denis stayed with her, and their younger boy Volodya lived with his father.

“A war started between my husband and me. He provoked me, and I responded in kind,” Martusova remembers. “He screamed that he would make sure I ended up destitute, playing the accordion in the market and begging for money. He took everything we had saved up over the years. And in our fighting, we forgot that Vova was 15 years old.”

According to Martusova, when her ex-husband remarried, her son felt that he had been betrayed and began searching for a new family — one more like Don Corleone’s. It was then that he started a gang with his friends. At the same time, “to reduce his sense of guilt, his dad started giving him expensive cars (which he drove to school) and began teaching him about life. He explained that power is all that matters — that everything nowadays is based on disorder,” Martusova says. She believes her ex-husband even asked their son, when he was 16, to “deal with” some of his business partners.

In 2008, when he was 20 years old, Vladimir Martusov was arrested and charged with armed robbery. The prosecution accused Vladimir of organizing a gang of seven people that specialized in stealing industrial equipment. More specifically, they were accused of stealing two truck cranes and shooting both drivers. One of the men survived with a severe disability, and the other was killed. Vladimir’s mother argues that her son’s role was only to sell stolen items and that he did not himself participate in the robberies.

“When they arrested him, they beat him half to death — I think he was even clinically dead,” says Elena Martusova. “He doesn’t have a single solid bone left in his face. For the next half year, they beat him in the pretrial detention center, interrogating him. In the end, he was diagnosed with a second-degree disability, and the court declared him unfit to stand trial.”

Martusov spent about five years in mandatory rehabilitation at a psychiatric treatment center and was released in the summer of 2015. For the next six months, his mother says, Vladimir tried to return to normal life: “The situation in the city is so bad that people don’t get hired even if they finish college, so there’s no hope for someone with a criminal record, let alone someone who’s on the list at the psychiatric ward.” Martusov developed depression and suddenly stopped taking his medications. He subsequently suffered a breakdown.

In December 2015, a half a year after his release from the psychiatric institution, Vladimir Martusov attacked a businessman named Evgeny Sarsenbaev, stabbing him 18 times. Sarsenbaev survived, and Martusov was arrested the same day. The businessman argued that Vladimir had acted on his father’s orders (Sarsenbaev rented a storage facility for fish from him). Vladimir, meanwhile, said committed the attack because Sarsenbaev had forced him to kill one of his business partners and even paid him six million rubles (about $100,000) for the job.

“Whatever happened in Sarsenbaev’s car that evening, my son had no right and shouldn’t have let it turn into a knife fight,” Andrey Martusov told journalists after his son’s arrest. “This has cast a shadow over our family. We denounce what he’s done, but we won’t disown him.” (Meduza was unable to contact Mr. Martusov directly.) In December 2016, a court pronounced Vladimir Martusov mentally competent and sentenced him to 14 years in prison for attempted murder and for armed robbery eight years earlier.

Before his sentence took effect, Martusov committed another crime in his jail cell in Angarsk. On January 17, 2017, a 49-year-old man accused of murdering his female roommate was placed in Martusov’s cell. The man was heavily intoxicated and was unable to control himself. “The other men in the cell later said that this man threw himself on Vova, and Vova instinctively kicked him. The other man fell, his back hit a chair, his liver ruptured, and he died. Vova suffered a lot after that — he couldn’t sleep for several months,” Elena Martusova says. The Angarsk City Court pronounced Vladimir Martusov guilty of willfully causing extreme injury and surpassing the bounds of necessary self-defense, but it did not increase his sentence.

Vladimir was supposed to spend another four years at a top-security facility in the village of Markova (not far from Irkutsk), but the court took into account the time he’d spent in the psychiatric facility and in pretrial detention. “He told me and his father, ‘Why don’t you abandon me? I’m a failed man.’ But we had already abandoned him before when he was 15,” says Elena, adding that Vladimir finally became “disillusioned” with the romance of criminality in prison, where he asked to be placed in solitary confinement, to avoid contact with the prison’s criminal cohort.

“When they took him away for the second time, I found a notebook in his things where he had written down a list of his good characteristics and the ones he needs to work on,” Martusov’s mother continues. “I read it, and it even made me laugh. In one column, he wrote: empathy, sympathy, humanity. In the other: arrogance, hubris, impulsiveness, lack of self-control.”

Six years ago, Vladimir’s son Lev was born. He lives in Irkutsk with his mother, who has not spoken to Vladimir for several years. “He always asks about [Lev] and asks us to get him into some kind of nice sport — something like swimming or gymnastics. And his mother wants him to start doing ballroom dance. I visit them, but we’ve decided not to tell Vova about that yet,” says Elena. “At one point, my son asked me: ‘And if I were gay, would you still love me?’ And I told him, ‘Sure, I’d love you.’ A gay person is probably better than a murderer. Or is a murderer better than a gay person? I don’t know.”

Story by Sasha Sulim reporting from Irkutsk, Ust-Kut, and Angarsk, translation by Hilah Kohen